Contents

Publishers Weekly — Michael Cuneo: ‘I Don’t See Myself as a Traditional Academic’

Dateline NBC — ‘American Exorcism’

Time — Did Mother Teresa Need an Exorcist?

St. Louis Magazine — Touched by Evil

Salon — The Devil’s Playthings

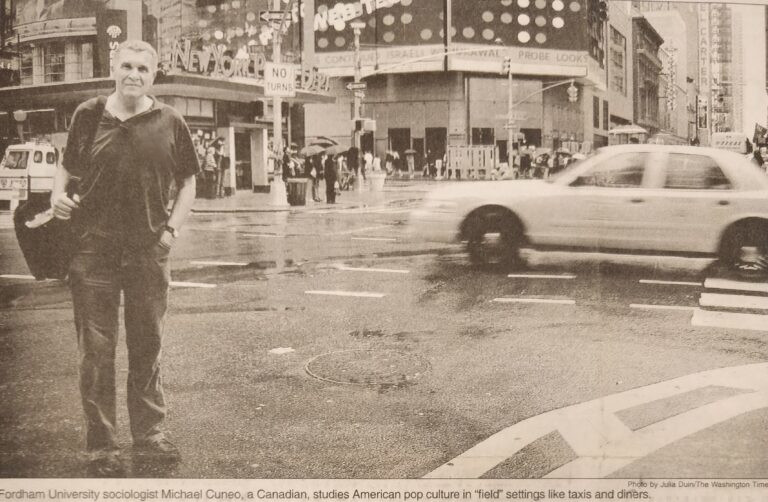

The Washington Times — Michael Cuneo: ‘I love the roads, the highways, the 24-hour diners’

New York Press — The Exorcist IV: The Skeptical Canadian

Inside Fordham — Sociologist Searches Out the Soul of the Country in Hidden Corners

Christianity Today — Exorcism Therapy

Dayton: The College — Murder and John Paul II

The Kansas City Star — Almost Midnight at Rockhurst: Michael Cuneo in Town Wednesday to Discuss his Book on Ozarks Murders

The Sentinel (Stoke-on-Trent, UK) — On Health: An Interview with Michael W. Cuneo

Toronto Star — Catholics Squabble on Abortion Unity

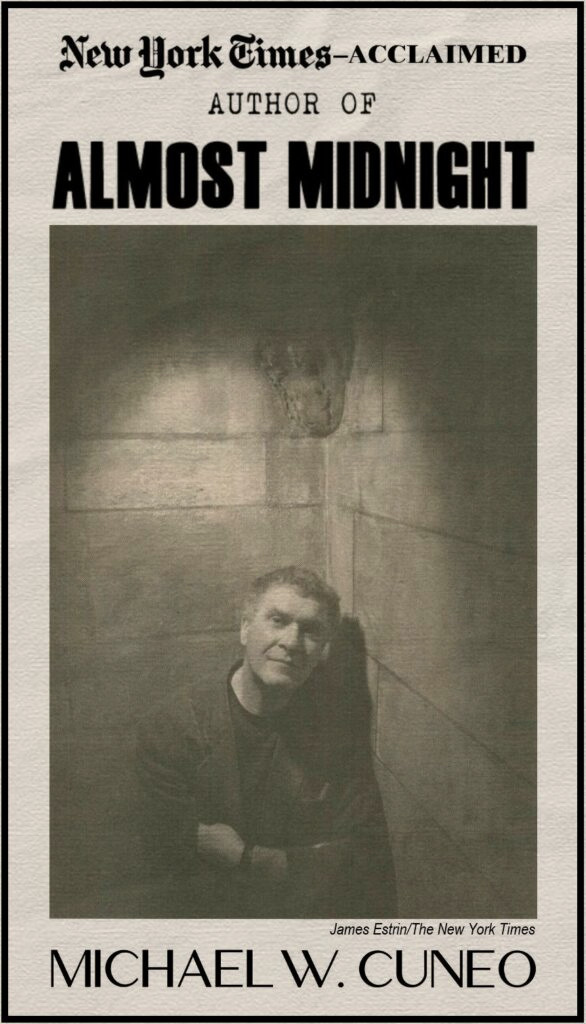

Publishers Weekly

Michael Cuneo: ‘I Don’t See Myself as a Traditional Academic’

By Juli Cragg Hilliard

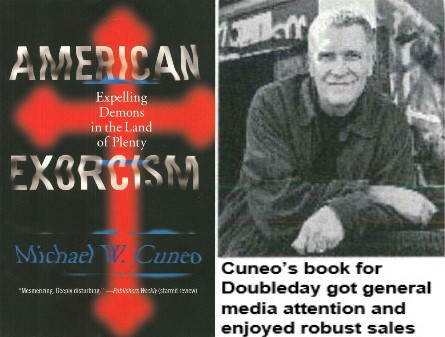

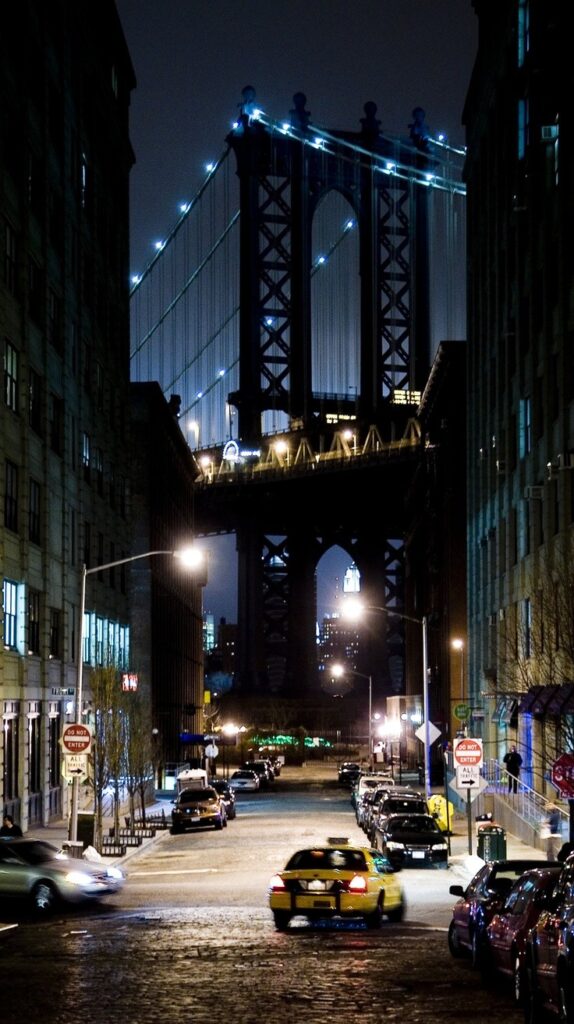

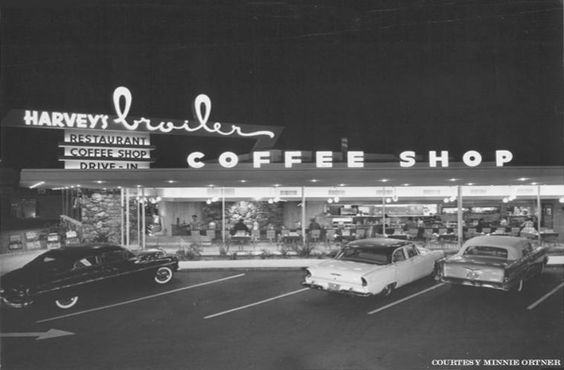

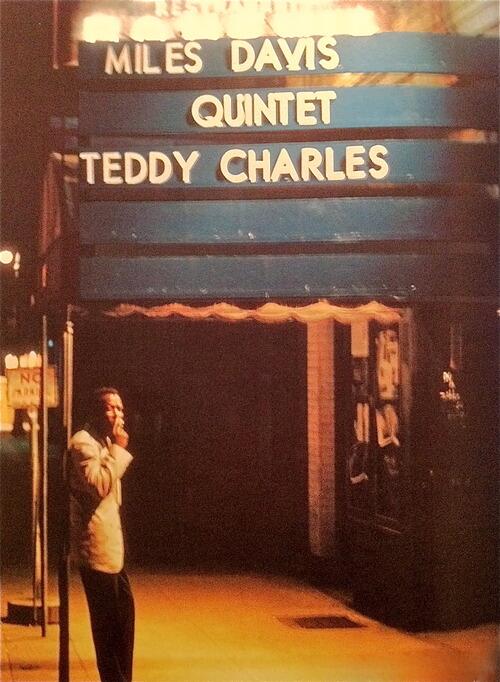

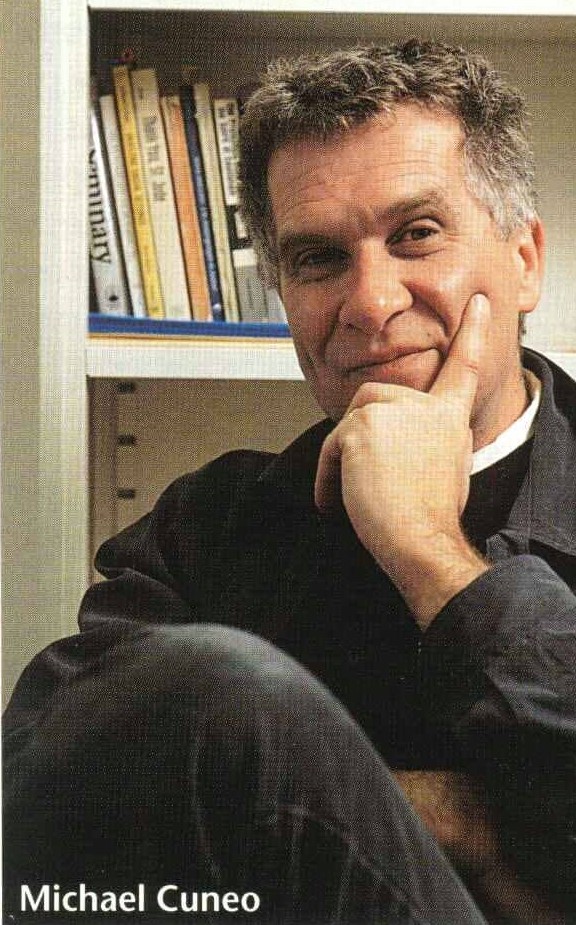

MICHAEL CUNEO HANGS OUT in all-night waffle houses, bargains down the rates in cheap motels, and sleeps in his rusty 1989 Pontiac to hunt down information on American culture and religion. He’s a professor of anthropology and sociology at Fordham University in New York City, specializing in the academic study of religion, but he spurns ivory tower life. ‘Front-line, hands-on research,’ as he calls it, scarcely seems an adequate term for the full-immersion style of investigation he uses for books like American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty (Doubleday, 2001; Broadway Books paper, Oct. 2002).

In pursuit of ‘anthropological journalism or journalistic anthropology,’ Cuneo applies the skills he learned as a cabdriver, and son of a cabdriver, in Toronto—hustling, working the streets, interacting with a variety of people. When he decided to move from scholarly publishing to the general trade, he saw little downside. ‘I was thinking almost entirely in terms of rewards because I don’t see myself as a traditional academic in the first place. I’m not really sedentary. I’m not really sedate.’

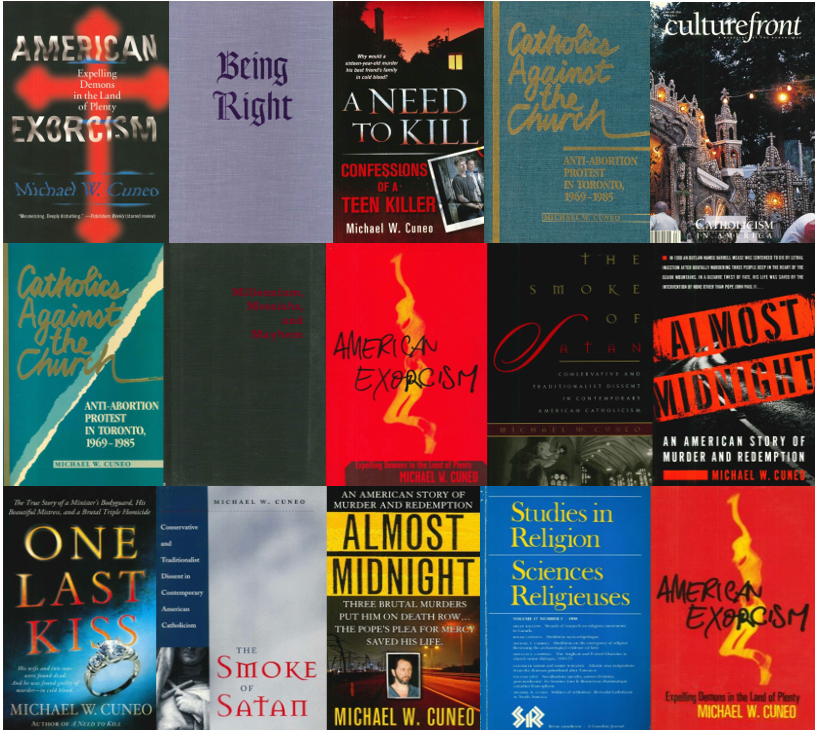

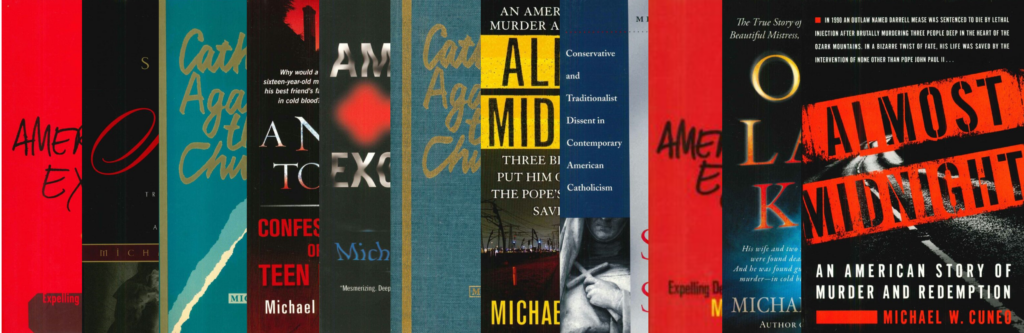

Cuneo’s first two books—Catholics Against the Church: Anti-Abortion Protest in Toronto, 1969-1985 (Univ. of Toronto; 1989) and, with Anthony J. Blasi, The Sociology of Religion: An Organizational Bibliography (Garland Pub.; 1990)—were hardly geared for the masses. But when he was at work on a project for Oxford University Press, his children said something like, ‘That looks like it might be interesting. Why not write it so somebody would want to read it?’ The result was the well-received The Smoke of Satan: Conservative and Traditionalist Dissent in Contemporary American Catholicism (Oxford, 1997; Johns Hopkins Univ. Press paper, 1999), about U.S. Catholic conservatism.

That is where Cuneo says he made a breakthrough. He already had started to mix up his reading, alternating between academic and well-written popular books, Max Weber followed by Janet Malcolm. Then, at 3 a.m., while laboring on Smoke of Satan, he struck on a passage. ‘Michael, just be a writer,’ he told himself. He started believing he could do it. ‘That was a real turning point,’ he says. People who work in general trade publishing read that book, and while Cuneo was conducting research on Americans’ fascination with exorcism he received a letter from Doubleday editor Andrew Corbin expressing interest.

Cuneo says now he lets his excitement about a subject carry him, and doesn’t worry about his reputation as a scholar. ‘I never write my books looking over my shoulder, looking for approval. I never ask permission,’ he says. ‘I’m never asking myself, ‘I wonder what the academy is going to think of this.’ Though a lot of academics believe that the conventions of academic writing can be stifling and suffocating, he says, ‘cultural elitism’—the sense that you’re writing for people who are intellectually superior—keeps many of them writing only for scholarly audiences. Moreover, it’s safer to write for your tiny universe of peers.

In August, Cuneo was praised at the annual meeting of the Association for the Sociology of Religion in Chicago but he knows it could easily go the other way. ‘I’m sure there are other scholars—and I’m sure I will be hearing from them—who would argue that my writing is not sufficiently academic, that it’s too freewheeling and lacks the proper deference to the traditions.’

Traditional academics would write a formal proposal and look for funding, he says. Their first impulse is to speak with other scholars. Cuneo, self-described ‘scholar-cabdriver,’ hits the road without money, rents showers in truck stops, and does most of his writing while drinking coffee in diners. ‘To me that’s so inspirational: writing on the move,’ he says. He’s 48, and the oldest of his four children just got married, but Cuneo says he still views himself as a guy in his 20s, just hitting his stride.

Cuneo’s next book, scheduled for cloth publication by Random House’s Broadway in January 2004, delves into a triple homicide in the Missouri Ozarks, set against a backdrop of Pentecostalism. Cuneo says the Pope makes a cameo appearance.

Cuneo didn’t buy a new car with his Doubleday earnings. He recently put the Pontiac, now with 330,000-plus miles on it, in the shop because he wants to keep the old sedan going. ‘I can’t see myself changing my style.’

Dateline NBC

‘AMERICAN EXORCISM’

Author Michael Cuneo writes about the real-life battle of good vs evil

MOST OF US remember the movie “The Exorcist” when a priest was battling Satan. And for most of us it was a revelation that the whole thing wasn’t simply made up. In fact, exorcisms really are performed – as many as 10,000 in the U.S. every year – and most of them not by Catholic priests but by evangelical Protestants. Read an excerpt of Michael Cuneo’s “American Exorcism” and see if you believe.

Time Magazine

By Jessica Reaves

IT’S A STORY that’s sure to leave heads spinning: Wednesday morning, CNN reported that Mother Teresa was the subject of an exorcism during her later years. According to the report, Henry D’Souza, the Archbishop of Calcutta, observed the late nun in an “extremely agitated” state while she was hospitalized for cardiac problems. She would appear perfectly placid during the day, then toss and turn at night, pulling off the monitoring wires that were attached to her arms.

D’Souza diagnosed Mother Teresa as possessed by the devil. The solution? To have the rite of exorcism performed. The nun reportedly agreed, and the Archbishop called in a “holy man” who commanded the evil spirits to leave the elderly woman’s body. After the exorcism, D’Souza says, Mother Teresa “slept like a baby.”

Why would Satan choose to possess one of the world’s most pious and best-loved figures? Was an actual exorcism actually performed over Mother Teresa’s bed? Does this story hurt the nun’s bid for sainthood? In hopes of finding some answers, TIME spoke with Michael W. Cuneo, a professor of sociology and anthropology at Fordham University and author of the new book “American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty.”

TIME: If you believe this story, it seems that this exorcism was ordered in pretty hurried circumstances. Isn’t there a specific set of conditions that need to be met before anyone conducts an exorcism?

Michael Cuneo: In theory, yes. That’s the way it’s supposed to go.

The official Roman Catholic position is that you’re supposed to approach an exorcism with a great deal of skepticism. Before ordering an exorcism, a priest is required to conduct a thorough review, eliminate every other possibility for the subject’s behavior — including psychopathologic and organic disorders. Even once you’ve ruled this out, you rule it out again. One of the weirdest things about this story, if the article is correct, is that there was no evaluation on the part of the Archbishop. The order for the exorcism was just off the cuff. Our biggest handicap in analyzing this story, of course, is that we don’t know how trustworthy the article and its sources are. So we have to approach all of this with some skepticism.

TIME: Let’s assume this is a true account, and Mother Teresa was in fact the subject of an exorcism. Does this obstruct Mother Teresa’s path to sainthood?

Michael Cuneo: I can’t imagine this would hurt or prejudice the campaign to have Mother Teresa declared a saint. If anything, the report will enhance her stature. Her advocates and defenders will say this is all the more proof of her piety — after all, Satan and his minions are often eager to attack the truly holy.

Beyond that, there is also a tradition here. According to Roman Catholic lore, holy men and women are often tested somewhere down the line. For example, Jesus Christ was supposedly assailed by demons during his earthly ministry.

TIME: Is it possible that this so-called “exorcism” was actually part of another rite, like a prayer for the sick?

Michael Cuneo: That’s what I initially thought when I read this story, because there is a prayer called the rite of deliverance that is a kind of informal exorcism, and is often performed at baptisms and over the bed of the dying. But if you take the story at face value, the phraseology that D’Souza uses, like “in the name of the church, I command you,” seems to indicate this was a fairly formal procedure. But again, we don’t know exactly what happened — we have to take D’Souza’s word for it.

St. Louis Magazine

Touched by Evil

It happened here, 65 years ago. A teenage boy was freed of whatever had possessed him. And people are still talking about it.

By Jeannette Cooperman

[excerpted]

EVERY ELEVATOR in Saint Louis University’s library is cranking its way up to the third floor, and the wide staircase is packed three across, with students jogging up three flights past lumbering alumni and wheezing senior faculty. Every chair on the second floor and the third-floor mezzanine is taken; people stand against the walls, umbrellas dripping cold rain.

They’ve come to hear about the exorcism.

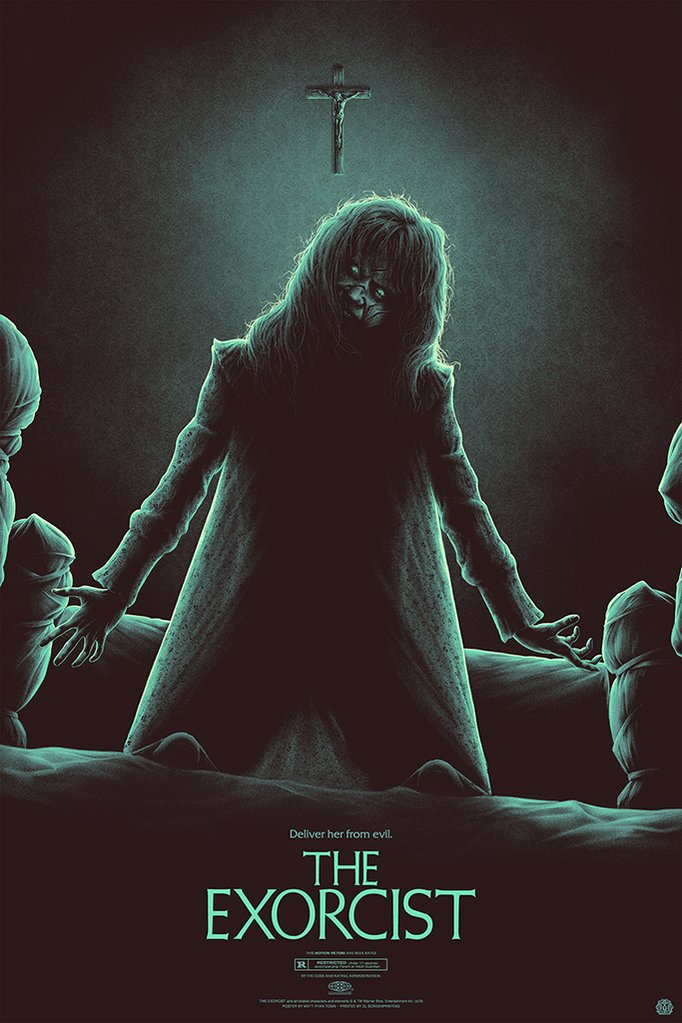

SLU is marking the 40th anniversary of the movie The Exorcist, inspired by a real-life exorcism that took place a stone’s throw (or a hurled crucifix) away from the library.

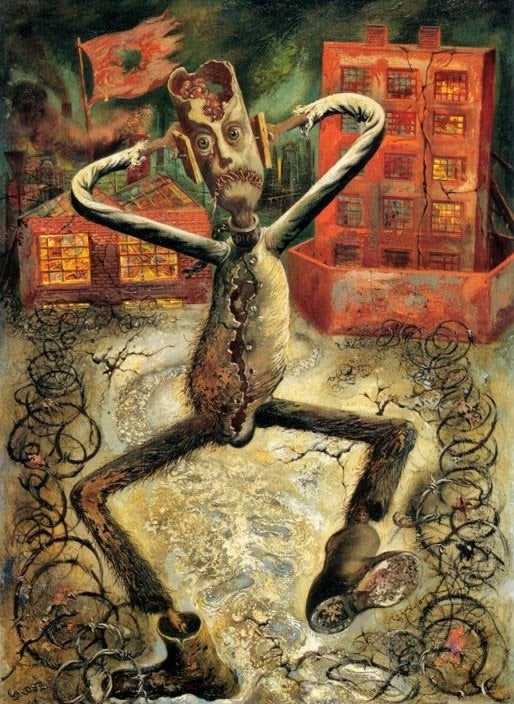

“If I had been there, I rather doubt that I’d have seen the things that were reported,” says Michael Cuneo, author of American Exorcism. “I’m a bit skeptical, but it’s a skepticism born of experience, because I don’t know anybody who’s attended as many exorcisms as I have. I was in a lot of situations in my research where people were seeing levitating bodies and spinning heads, all the demonic grotesqueries, and I was the only person not seeing this stuff. It’s almost a collective hypnosis.”

After watching dozens of exorcisms—some performed unofficially by charismatic Catholic priests and some by evangelical Protestants—Cuneo has decided they really can be therapeutic. Clergy members name the person’s problem, tell him it’s not his fault at all, and then take the problem away. The process has an emotional intensity our healthcare system lacks, and it’s cathartic, releasing pent-up anxiety, lust, and aggression.

“You have a license to act out in any way that you want,” Cuneo explains. “People will simulate masturbation; they will rip their hair, shred their clothing, physically attack other people. It’s one of those rare occasions in life where whatever you do, it’s not held against you, because it’s really your demons acting out.”

On the other hand, Pope Francis warns of psychologizing Satan’s work. And even hard-bitten reporters have asked Cuneo, with voices lowered, “Is it real? Did you see anything?”

“We live in a secular age, but we cling to the possibility of mystery,” he says. “We don’t want to think that all this banality exhausts life. There’s a real hankering for supernatural drama.”

Talk of diabolical possession especially raged in the ’70s and ’80s.

“It’s not at a high ebb now,” says Cuneo, “but it’s by no means extinct. You saw that at the library. And I get frequent media requests to talk about it.”

Salon

The Devil’s Playthings

Michael Cuneo traveled across the U.S. observing exorcisms. He talks about the strange things he’s seen and the likelihood of demonic possession

By Suzy Hansen

IN 1971, William Peter Blatty published the bestselling book “The Exorcist,” based on a 1949 newspaper story about a Washington, D.C., 14-year-old. After being tortured by mysterious scratchings and rappings on his bedroom walls, the seemingly incurable teenager was exorcised by a Jesuit priest. Blatty’s version, however, concocted the much more romantic and outlandish story of Regan, a young girl unforgettably played on screen by Linda Blair, who would make her mark spewing vomit and masturbating with a crucifix while being exorcised by dashing and charismatic priest heroes.

Michael W. Cuneo, a Canadian-born professor of sociology and anthropology at Fordham University in New York, knew that “The Exorcist” took the world by storm, but he never imagined how many Americans might take it as a hint to sign up for exorcisms themselves. His latest book, “American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty,” is a wild exploration of the spookier and more fantastical side of Middle America. After two years of attending exorcisms across the country, Cuneo judiciously details how popular entertainment has fed Americans’ thirst for demon expulsion, what really goes down at a legitimate Roman Catholic ritual and what leads people to believe that they have succumbed to demons.

Salon spoke to Cuneo at his home in Toronto.

How did the 50 exorcisms that you saw affect you?

There wasn’t any time when I thought, My goodness! There really are demons in here and there’s a chance that when they’re liberated from one person, they’re going to invade me! Lots of people that I interviewed during the research were concerned about that.

What, that you had demons?

Oh, yes. And quite understandably. They would say, “Look, Michael, you’ve been doing this very dangerous research. You’ve been exposing yourself to preternatural evil, a supernatural whore. It only stands to reason that you yourself would have succumbed to some kind of demonic contamination.” Sometimes I would be the only person in the room who didn’t see it. People would say that that was because I’m a writer. Satan doesn’t want to blow his cover.

Did they offer to exorcise you?

Many people wanted to exorcise me. They claimed to know that I was infected by demons, and other people, the very next day, would just as confidently give me a clean bill of health. But for all of my human frailty and the personal evil I’m capable of, I felt that demons had nothing to do with it.

Was this frightening at all?

They wanted to exorcise me out of good will. They thought that I’d put myself in harm’s way and that demons had found an opening in me. There were times when I was involved in scary situations. During one public or mass exorcism, the exorcist, Pastor Mike, was exorcising a really big dude. He started thrashing and punching and spinning people around.

Where were you?

I had just had lunch with Pastor Mike in the Chicago area. I really liked him and thought he was a cool, unpretentious, humble guy. Then, at the exorcism, at the front of the auditorium, the guy who Pastor Mike was exorcising let loose horrible shrieks of impassioned rage. He picked up Pastor Mike and started spinning him around. Pastor Mike’s glasses flew off. The exorcisee seemed capable of inflicting horrible violence on Pastor Mike. A couple other guys tried to subdue him and he was punching and kicking them.

So I slowly took my jacket and my glasses off and very gingerly walked to the front, all the while hoping that things would resolve themselves by the time I got there. I wasn’t up for any kinds of heroics. I put a headlock on the guy and he spun me around as well. Eventually, about five of us got him to the floor. For the next hour, I was lying there on the floor just pinning one of his arms down in the sweltering heat and humidity.

What was wrong with this guy? What demons did he have?

Demons of rage.

Surprise. Rage demons.

Rage and frustration. Pastor Mike identified a whole slew of them. At one point, Pastor Mike started arguing with the demons — while we were all lying on the floor holding this fellow down — saying, “You’re sorry excuses for demons! You’re weak! You’re useless! Come out, you demons. You’re the most useless demons I’ve ever encountered.”

Professional Films, Inc.

Did they scream back?

Yes, they were screaming back, “You’re a fucking faggot, Pastor Mike! We’re going to kill you!” There’s some real violence there.

Rage sounds interesting, but isn’t sexual appetite the most commonly exorcised demon?

It’s among the leaders. I would say it’s top 10 in the hit parade. Sexual infidelities, demons of sexual perversion, demons of runaway sexual appetites. I ran into that a lot.

Is it assumed that these demons are the devil?

They’re working for the devil. They’re in league with the devil. They’re the devil’s assistants. Where else do you get a more vivid and intense supernatural drama, where the mythical forces of good and righteousness are lined up against the mythical forces of perfidy and evil? Where else is this more dramatically occasioned than during an exorcism?

Were the faces of the people being exorcised disturbing?

Yeah, yeah …

But not quite like Linda Blair?

No, I’ve never seen anything like that.

No spinning heads?

Nope.

Vomiting?

Lots of vomiting. Regurgitating. Shredding of clothes. Yanking of hair.

Did they masturbate with crucifixes?

Mostly, it’s simulated masturbation or pounding at the groin or gouging at the groin. And screaming and howling. People throwing themselves on the floor and slithering like snakes. I thought many of them were playing to the occasion. The exorcist is up there sweating and working so hard. A team of people are praying for you. At some point during this whole dramaturgy, you want to do your part.

Are the exorcists reciting prayers?

Yes. In the Roman Catholic case, sometimes they are pressing a relic against the person’s forehead or splashing the person with holy water. People will engage in highly dramatic manifestations. I absolutely didn’t see anything that left me sheet-white and palpitating in fear. I never saw levitating bodies. I never saw navel-licking tongues. I never saw the perfect, classical Latin speeches. I never saw the preternatural strength. I never saw things that could not be accounted for in rational, secular terms.

Did you go into all of this with skepticism?

Yes, but I am Canadian. I told people that I was going to approach it with an open-minded Canadian skepticism. Canadians are a circumspect, prudent people. I told myself to take this stuff seriously, try to be respectful, do not preclude any possibilities whatsoever and be prepared for anything. After all, what do I know? But when people are telling me that they’d just been raped by succubi and incubi the night before or that they were inhabited by 1,001 demons, I knew not to take it at face value.

The people in your book are mostly Americans. Did you immediately choose to focus on America? Do these things go on in Canada?

We have some exorcisms in Canada, but it doesn’t go on to nearly the same extent. Religion in the United States does have a more feverish, highly sexualized and raw component to it. Also, I wanted to focus on the United States because very early on it occurred to me that a lot of the stuff I’d been witnessing had been deeply influenced by the American popular entertainment industry. So many of the people claiming to be demonized would not have done so had it not been for William Peter Blatty’s book “The Exorcist” and William Friedkin’s movie of the same name and Malachi Martin’s “Hostage to the Devil: The Possession and Exorcism of Five Americans” and M. Scott Peck’s “People of the Lie: The Hope for Healing Human Evil.”

What was it like after the movie “The Exorcist” came out in 1973?

The chronology seems pretty clear-cut to me. By the mid-’60s, exorcisms had been a dead issue. Who the hell talked about exorcism? It was practiced in certain backwater cultural pockets in the United States but it wasn’t all the rage. Then, William Peter Blatty’s bestselling novel “The Exorcist” was published in 1971. There was a real explosion right after that. Satanism scares blossomed in the early 1980s and 1990s to the point where people couldn’t turn on the television without all this glitz-and-gloom coverage of satanic ritual abuse.

What happened was that the popular entertainment industry wound up generating tremendous popular fascination with exorcism. We’re impressionable and we’re gullible and we’re so highly suggestible. It’s this rock ‘n’ roll phenomenon. Priest exorcists become celebrities. They are like the last of the lonesome gunfighters.

Still: demons? Why would anyone want to believe they had demons inside them?

Imagine someone sitting in front of their television screen, being bombarded by images of demons. They might be experiencing some intractable disappointment of life or some deep-seated psychological problem. They may have tried conventional psychotherapy. Yet, the thing has not gone away. They see these images of demonization and think that maybe that’s their problem. And in the tradition of good old Yankee experimentalism and pragmatism and perfectionism, they say, “I’ll give it a shot and see if it does the trick.”

There’s another factor. The United States is a therapy-mad culture. Exorcism might be the crazy uncle of therapy, but dammit, it’s therapy. It’s wondrously in tune with the therapeutic ethos of the prevailing culture in the United States. It’s really cheap. It’s relatively fast. Most of all, it’s morally exculpatory. We live in a culture of victimization where the whole point is to blame someone else for our shortcomings. Here, the demons are to blame. It takes place everywhere else, but in the United States it just makes so much more sense.

Did people know when the movie came out that it was based on the book and that the book was based on a true story?

Yes, most people were aware of that. That’s what gave the movie so much mystique and panache and cultural prestige. There was so much publicity surrounding that case. People thought that what they were seeing on-screen might not literally be true, but still thought that something like this had taken place. And if it has taken place in the United States of America, the most advanced, industrialized, technocratized place, then it could take place again and probably is.

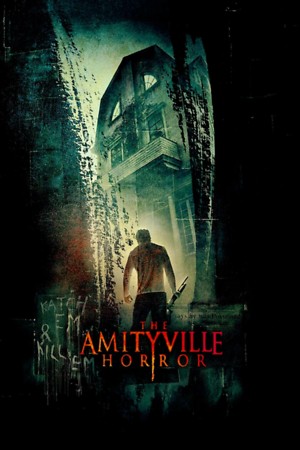

“The Amityville Horror” was based on a true story too. That’s another kind of exorcism — expelling demons from a house. Is that common too?

It is very, very common. And that was Ed and Lorraine Warren’s claim to fame. They were the first self-professed psychic sleuths on the scene who really claimed to have diagnosed everything that was taking place there. The house is still there — 112 Ocean Avenue. A friend of mine took me out to Long Island to see it, on a rainy day with the mists blowing in off the water …

Does anyone live there now?

There were people walking in and out. You can clearly identify it.

What did the people who originally lived there claim was going on with their house?

This young couple, the Lutzes, purchased the house and claimed that they witnessed all kinds of bizarre and frightening and hideous phenomena — shriekings and so forth. They eventually discovered that the previous occupants had experienced a horrible tragedy. Just a year previously, Ronald DeFeo, one of the sons, shot to death his parents and four younger siblings. When the Lutzes moved in with their three kids, there were these bizarre, unexplainable knockings and rancid odors. Slime oozing from the walls and flies swarming on the bedroom windows. It freaked them out to the point where they broke and ran. Then the Warrens arrived on the scene and took care of business.

Did they take pictures of this? You said you saw some of the Warrens’ videos. What did you see in the videos?

With so much of this stuff I have a real problem. I have so much affection for Lorraine and Ed Warren. They’re marvelous people and real showmen. But everything about them does strike me as suspicious. I don’t want to say that anything in the videos was doctored. I don’t have the authority to say that. But I would be very suspicious.

Didn’t they deal with a man who claimed that he woke up to demons having sex with him?

Right. That was a guy who claimed that night after night, he was being ravaged by some gorgeous demon while he was sleeping beside his wife in their marital bed. This gorgeous demon was performing sexual acrobatics on him while he was numb. Then he’d have to shower to wash her gelatinous sexual deposits off of him. It’s just too beautiful.

Were most of these people that you met very religious to start out with? Who are they?

The biggest market for exorcism is in Middle America, white bread America. Indiana’s big. Ohio’s big. Then again, I saw a lot of stuff out on the West Coast and a lot of stuff on the Eastern seaboard. And a lot of stuff in New Orleans that I don’t even get into.

New Orleans gets its own book, huh?

New York and New Orleans don’t even belong in the republic. Yes, the majority of the people who were going for exorcisms were religious. They were Christians. But there are people who are self-professedly agnostic and who do not have strong religious commitments who also seek them.

Can you break down what the differences are between the types of exorcisms? What’s the difference between Roman Catholic and Protestant exorcisms?

There are strong similarities. First of all, the kind of exorcism in the United States that has the most prestige by far is the official Roman Catholic exorcism, which is performed by an officially appointed Roman Catholic priest exorcist. That’s what the media wants.

Does the Roman Catholic church have an official stance on this?

The official Roman Catholic position is that full-scale diabolical possession can take place but is so unlikely and so far-fetched that never, never under any circumstances should anyone assume that demons are present in any particular case. Rule out all other possibilities: psychopathology, neurological disorder, paranormal possibilities and fraud. And once you’ve ruled them out, rule them out again.

Not all priests can do this then?

You’re supposed to be officially appointed to that role by the bishop. No one else is supposed to do it. Up until the mid-1990s, there were only one or two officially appointed priests in the United States. As of 1994, my best sources tell me there was only one. Now there are a dozen closing in on 15. There was a tremendous demand for official exorcisms, yet people couldn’t get them. What happened then was that a flourishing underground exorcism movement arose within Roman Catholicism where maverick priests would wind up doing bootleg exorcisms. It was the second best thing.

What is the Roman Catholic ritual like?

It’s a beautifully written 400-year-old ritual. The first one I attended most moved me. It took my breath away and sent shivers up my spine.

Where was it?

I can’t say. To get into those exorcisms took unbelievable maneuvering. For months I was seeking out officially appointed Roman Catholic priest exorcists. I had all these sources and was digging and digging and finally wound up in a diner with this guy. I just knew it. I said, “Wait, you’re an officially appointed priest exorcist aren’t you?” And he just smiled. I said, “Can we talk about that?” I wound up going to some of his exorcisms and some others. But to get in I had to assure confidentiality.

How many of them happen a year?

I attended six of them in one year. I would say that’s a big number. Normally, it would be no more than two or three.

Do the priests or ministers charge money for this?

No. Donations are welcome. There isn’t a fee schedule like $200 dollars for demons of sexual infidelity, $500 for demons of depression. Some people are doing it out of sheer power-tripping. You can imagine what a heavy thing it is to sit someone down and tell them they’re demonized. Not only that, but being able to tell someone, “I can ascertain the precise names and identities of your demons, the number of them, their ranks and their purposes. I have an infallible gift of spiritual discernment.” How the hell do you disagree with that person? It’s all nonfalsifiable stuff!

Is one person exorcised at a time?

The priest exorcist, with certain assistance, will exorcise one person at a time. One of the things that really astonished me was the presiding psychiatrist; the ones I met were Ivy League-trained people. They weren’t cranks and misfits.

Do they believe in demonization?

The psychiatrist says that they’re pretty sure there’s no demonization and the priest exorcist agrees. They attend for strictly pastoral reasons. The exorcisee is so absolutely convinced that they’ve become demonized that their life has become paralyzed. They’re not able to carry on. Their family is falling apart. They have been fired because of dereliction to duty. Not only that, but they’re so convinced that they refuse to entertain the possibility of receiving other kinds of treatment. The priest gives these people an exorcism so he can satisfy this in their mind and say, “Now you’ve had your exorcism. If there were demons present, the demons should have been routed. If your problems are continuing, then it’s something else.” And very responsibly, they set them up with counseling.

So some people didn’t feel cured afterward?

One person thought that he needed more exorcisms. The exorcist said no and set him up with psychiatric treatment.

That’s pretty nice and responsible of them.

Sometimes, yes. At Protestant exorcisms, there’s more of a presumption of demonization. There isn’t the same screening. The very rich ritual doesn’t tend to go with it. But let me say this: I found some of the evangelical Protestant exorcisms — they use the term “deliverance” — very impressive. The exorcist asked such probing spiritual and personal questions at the start, then very sensitively performed the deliverance. At some of these, I thought that even if there were not demons present there, something good has happened. It could just be the placebo effect. They’re the center of attention. All these well-meaning, earnest people want to see them heal. They can talk in very intimate terms about whatever they perceive their problem to be. There’s a powerful expectation of getting better.

But people have died during exorcisms.

Yes, there have been some horrible tragedies. The worst involved the 17-year-old girl in Long Island. They were Pentecostal. In this case, an older daughter and a younger daughter were helping the mother perform the exorcism on a third daughter. Then the mother apparently threw her arms up and said that this was not their sister anymore. The demon had fully taken her over. She asked the younger daughter to leave the room and when she returned, the middle daughter was dead. She had been suffocated.

That’s the exception. There have been five or six exorcism-related deaths, but most take place in a responsible atmosphere.

I’m sure you’re going to get phone calls now. What would you say if I called you up and asked you for one? Where would you recommend I go?

I’m just a writer. And I happened to write a book on exorcism. The last thing I want to be is a broker for exorcisms. That would be irresponsible of me. I’m not arguing that people should or shouldn’t be going to them.

A woman phoned me and said, “Michael, you have to help me. They’re in my eyes. The demons. They’re in my eyes. I can’t get them out.” Then she goes on to tell me that she teaches piano to young children and that these lessons were her only source of livelihood but the demons in her eyes were driving her to despair. Then I heard the doorbell ring. I could hear her greeting a young child. She invites the child in and they come closer to the phone and she says, gently and sweetly, “Now practice your scales.” I heard the clunk, clunk, clunk of piano keys, a young child practicing. Then she gets back on the phone and, “Michael, please help me, they’re in my eyes, please help me.”

Those are the kind of situations that drive you crazy. What is my responsibility there? Now I’m concerned about the kids. I asked her to promise me that she would phone her doctor. I never heard back from her again.

The Washington Times

Michael Cuneo: ‘I Love the Roads, the Highways, the 24-Hour Restaurants’

By Julia Duin

[excerpted]

MICHAEL CUNEO’S IDEA of field research is driving a big-city taxi, hopping freight trains, and delving into hillbilly murders in the Ozarks.

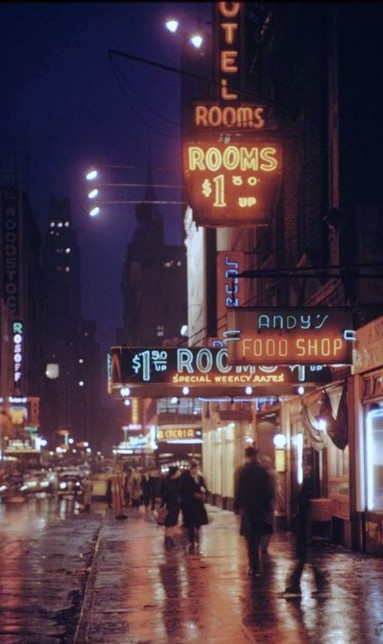

“Usually I’m hanging out at a 24-hour Denny’s or a Waffle House chain-drinking coffee and writing my field notes up,” he says.

Mr. Cuneo is actually Canadian, but he fishes about the lower 48 to enlighten students about the kind of iconic trends that dominate the world.

“Rock ‘n’ roll, jazz music and blues – they could only have emerged from the United States,” he says. “The combination of African, indigenous and down-home influences; you can’t imagine Elvis Presley’s music coming from anywhere but Memphis. Could anyone other than an American have written On the Road?”

Although natives may be used to the flora and fauna of American life, to the foreigner, life in the States is like stepping into a rainbow. Mr. Cuneo’s favorite spots are corners of the country like Spokane, Yuma, and Fort Wayne. They are cauldrons of the “intrinsic fascination, vibrancy, and internal dramas of the American scene,” he says.

“I love the roads, the highways, the 24-hour diners, the ordinary people you encounter,” he says. He is currently writing a book on a triple murder involving backwoods methamphetamine makers in the Ozarks. He just came out with another, “American Exorcism,” about the practice of casting out demons in the contemporary USA.

“Whatever one’s personal problem – depression, anxiety, substance addiction, or even a runaway sexual appetite – there are exorcism ministries available today that will happily claim expertise for dealing with it,” he writes. “Personal engineering through demon-expulsion: a bit messy perhaps, but relatively fast and cheap, and morally exculpatory. A thoroughly American arrangement.”

New York Press

A FEW YEARS AGO, Fordham sociology and anthropology professor Michael Cuneo gave himself what sounds like a fun assignment. He has since witnessed dozens of exorcisms across the U.S. as research for his new book American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty (Doubleday, 314 pages). When you ask him, however, as I did last week, how many head-spinning, bed-levitating, projectile-vomiting cases he’s observed, his depressing answer is: zero. In fact, to hear it from him, exorcism sounds positively boring.

Yes, he saw some spitting up, and one girl who did a little desultory slithering on the floor like a serpent. And some people do curse like demons during the process, and some jerk around in their chairs or simulate furious masturbation. But still, Cuneo—who grew up Catholic in Toronto and says he approached the subject with “openminded skepticism”—saw nothing like what the practitioners refer to as “fireworks,” nothing so spectacular as what was depicted in The Exorcist, or Poltergeist or even The Amityville Horror. Actually, most of the exorcisms he witnessed sound suspiciously like modern therapy sessions, somewhere between Rolfing, primal scream therapy and group encounter sessions, with a layer of Catholic or Christian liturgy on top.

“As recently as the late sixties, exorcism was all but dead and forgotten” in America, Cuneo writes, and reported cases of demonic possession in this country were extremely rare. The Catholic Church in this country had exactly no official exorcists on its priestly staff, and looked on the whole business as an embarrassing reminder of a more primitive and superstitious time.

Suddenly in the mid-1970s people all over the country (and around the world) were convinced they were possessed. The Catholic Church, and then Protestant and even Jewish clerics, were inundated with urgent demands for exorcisms. Belief in demonic spirits came back with a huge bang, and through the 1980s and 90s became associated with various other religious movements, like the spread of evangelical and charismatic groups. Naturally, it also fed on the Satanic cult conspiracy scares of the 80s and 90s.

Today, all sorts of priests, clerics and even laypeople are doing landmark business in casting out demons.

Why the sudden rebirth of this once-forgotten old custom into a full-bore worldwide fad? Cuneo argues a very simple, convincing and somehow demoralizing thesis: it all starts in 1973 with the release of The Exorcist, and is then fanned into a fad by a few popular books like Malachi Martin’s Hostage to the Devil (’76), The Amityville Horror (’77) and M. Scott Peck’s People of the Lie in 1983. “Exorcism became a raging concern in the United States only when the popular entertainment industry jacked up the heat,” he writes. The “dramatically increased market for exorcism that surfaced in the United States during the 1970s” was generated almost entirely by Hollywood and New York publishing, and “a highly suggestible public” ran with it.

Not all that surprising, Cuneo says to me. “This is our bible, what we see on the screen and in our TV room, and it has terrific authority. I don’t think there’s any question that the entertainment business was primarily responsible for galvanizing interest in exorcism at a popular level, for really stimulating the market for exorcism. And it wasn’t just [The Exorcist author] William Peter Blatty; there were so many movies that followed. My personal favorite was Kung Fu Exorcist,” he adds with a laugh.

The Catholic Church resisted this sudden new fad for demon-wrangling. For years, Catholic exorcisms were available only from a handful of renegade priests working in secrecy (most of them allied with those ultra-conservative Catholics who’d been resisting the modernization of the Church since the Second Vatican Council). Instead, it’s been various types of Protestants, interestingly, who’ve most enthusiastically taken up exorcism and embraced the new-old view of a world beset by demonic legions. Among both evangelicals and charismatics, a whole new exorcism industry grew up, going by the less-Catholic-sounding term “deliverance ministry.” Teams of deliverance ministers—as often laypeople as clerics—operate all over the country, casting demons out of believers in schools and churches and motel rooms. Looking nothing at all like the solemn Catholic ritual depicted in The Exorcist, the average session is much more dressed-down and quiet—Cuneo describes it in the book as a “ritual package” with “elements from primitive shamanism, backwoods Pentecostalism, and middle-class psychotherapy.” People come to the session tortured by, say, uncontrollable lust or “sexual perversion” (i.e., homosexual urges); the demons in them that control these urges are cast out; they go home “cured.”

Not surprisingly given our puritanism, American Christians seem particularly plagued by “demons of lust, or demons of homosexuality, or demons of bisexuality,” Cuneo tells me. “I would say half the exorcism rituals that I sat in on involved sexual demons. Depending upon geography, you would find the nature and the identities and the missions of the demons changing. In the United States, demons of sexuality play a huge role. It’s not accidental that Monica Lewinsky became absolutely huge in the United States, whereas in Canada we wouldn’t have given a shit. Can you imagine anyone in France caring?”

When I ask him how widespread this is, he replies, “If anything, I have understated [in the book] how popular exorcism is as a contemporary form of therapy. The United States is a therapy-mad society. Exorcism is perfectly in tune with the prevailing therapeutic ethos. Think of the advantages. First, it’s cheap. Very rarely do exorcists charge for their services. They don’t turn people away. Also, it’s relatively fast. A little messy, because there could be vomiting, but fast. And the best thing of all, it’s morally exculpatory, so it fits in beautifully with victimization themes of our culture. ‘Listen, man, it’s not me ultimately who’s at fault, it’s these damn demons! Get rid of the demons!’ It is wonderfully in tune with so many impulses in our culture.”

It’s so easy. Do people really seem to be cured when it’s done?

“I think in the short term at least a lot of people really do benefit from it, because it’s such a visceral form of release,” Cuneo says. “It’s such a cathartic experience. A lot of the people who go for exorcisms are pretty straitlaced. How many opportunities will they have to get down and dirty? To grovel and puke, to masturbate in a semi-public arena, to shred their clothes? This can be a purifying experience. They’re in a healing environment. What’s the key to any kind of psychotherapy really? Being in a supportive, healing environment where there’s hope or expectancy for improvement, where people get the benefit of some kind of healing minister. That’s what exorcism provides, a healing minister who truly believes in demons. The people going believe that they’re demonized. They fully expect that the procedure will be effective. They fully expect that their hitherto intractable psychological, moral and emotional problems will be resolved, that their demons will be expelled and that they will walk away cleansed and freed and liberated and ready to carry on with their lives. And very often for the short term it seems to work. A lot of this is pure bliss placebo—and I don’t mean to diminish that.”

“To their credit,” he adds, “many exorcists strongly recommend follow-up psychological counseling, and they’ll even help set it up. See, for a lot of exorcists, they’re not thinking in either-or terms—they’re not saying, ‘You’re either demonized or you’re suffering from some psychiatric syndrome.’ They think that it’s important to do the exorcism, but also that the person receives appropriate professional attention . . .

“There’s a long history in the United States of experimentation with different kinds of therapies,” he continues. “Exorcism fits in beautifully with that. There’s nothing dissonant about exorcism in American culture. It makes perfectly good sense.”

Although there are naturally some charlatans out there preying on troubled innocents, Cuneo insists that the vast majority of practitioners he met were earnest and sincere, and operating with “real pastoral adroitness. They’re nor doing it for money, they’re not doing it for personal glamour. They are absolutely convinced that there’s an epidemic of demonization and that they are called to do battle against this. To help people out. Most of the people I saw, I walked away thinking, ‘Well, if anything no harm’s been done.’”

In fact, he jokes at me, “If you want, I could put together a dream team of exorcists for you,” because he knows I’ve just got to have a lot of demons.

Cuneo’s been commuting between Toronto and Fordham for a decade. When he tells me he’s a “working-class guy, a long-time cabdriver,” I ask how he got from cab-driving to teaching anthropology.

“Long evolution,” he says. “My dad drove a cab, one of my younger brothers drove a cab, I did it. I spent two years hopping freights and hitchhiking all around Canada, the United States and northern Mexico, and encountered much freakier and scarier stuff doing that than I ever did doing the exorcism research—oh, and also much scarier stuff driving a cab. I eventually wound up going to the University of Toronto on a part-time basis, raising kids, earning a PhD, and coming down to the Bronx. I’m really a writer masquerading as an academic.”

American Exorcism is his third book. The one before it, The Smoke of Satan, was about conservative and traditionalist Catholics. “Which has nothing to do with supernatural evil or anything of the sort, but it was a funky, sexy title which made sense for that book.” He’s got two more books “in the hopper,” neither of which has anything to do with Satan—although one is about a grisly murder, which almost counts.

Inside Fordham

Sociologist Searches Out the Soul of the Country in Hidden Corners

By Patrick Verel

YOU’LL BE HARD PRESSED to find someone with more unusual interests than Michael Cuneo, Ph.D., associate professor of sociology and anthropology. Although he grew up in Canada, it’s the contradictions and quirks of America that fascinate him most. And his brand of Americana doesn’t feature apple pies, Independence Day parades or Disney World.

“I tend to be drawn to more of the funky, the offbeat, the eccentric,” he said. “Sometimes some of the more interesting and more revealing things are happening out of the mainstream.”

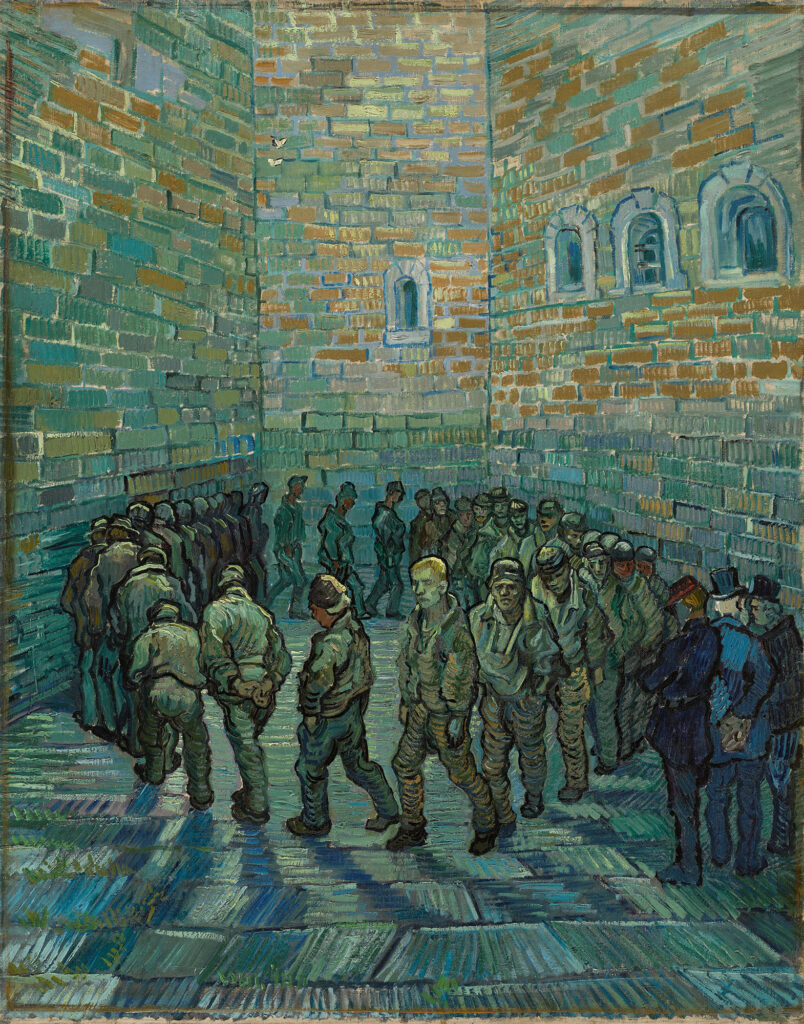

The pursuit of those out-of-the-way places has taken Cuneo to places that few Americans have heard of, let alone visited. To write American Exorcism, Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty (Broadway Books, 2001), he sat in on 50 exorcisms conducted by Christians around the country. For his most recent book, Almost Midnight, An American Story of Murder and Redemption (St. Martins, 2004), he ventured into the Ozarks, a mountainous region in southern Missouri and northern Arkansas.

There, he met Darrell Mease, a man who’d been convicted of a triple homicide and sentenced to die by lethal injection, only to have his sentence commuted to life in prison in January 1999 after Pope John Paul II made a personal appeal to the governor during a Papal visit to St. Louis. As if that weren’t bizarre enough, Mease had a religious awakening while on death row and began claiming that because God was his lawyer, he wouldn’t let him die. But while the book could have been merely “true crime” material, Cuneo approached it as an examination of the hillbilly subculture of the Ozarks that he says is full of paradoxes that make it unique.

“One the one hand, it’s a real outlaw culture, where historically they’ve celebrated the moonshiners and outlaws of various natures, because there’s a real mistrust of established authority and the laws and the courts,” Cuneo said. “So they’ve celebrated the outlaw. And then also, simultaneously, they’ve celebrated the preacher, the holy man. So, it’s outlaw culture on the one hand and on the other hand it is deeply steeped in spirituality.”

That aspect of American culture and religion is a common thread in his books Catholics Against The Church, (University of Toronto Press, 1989) and The Smoke of Satan (Oxford University Press, 1997), which like Almost Midnight have been reviewed in publications such as the New York Times, Washington Post, Boston Globe, New York Review of Books, Newsday and the New Yorker. Although he found in American Exorcism that the popularity of exorcisms increased along with the rise of the quick fix, therapeutic culture, he found in Almost Midnight a culture that did not condone a triple murder but was unfazed that God would save the perpetrator from death.

“It was taken as something which was providential, that was meant to be. Which was, in a sense, a mystery that mere mortals would probably never understand,” he said. “But, nevertheless, it was a religious mystery, a spiritual mystery.”

Cuneo, who has been at Rose Hill since 1990, blames the decline of subcultures like the Ozarks on economic factors like expanding residential development and big-box stores, but also the influence of popular culture.

“We wind up consuming the same thing, consuming the same movies, the same television programs, and so as we consume the same things, we become more alike, and local options are frittered away,” he said.

So how does one get to know people who are suspicious of authority and openly hostile to outsiders? “Some of my best research is undertaken in local bars and strip clubs,” he said. “Also, conversations with the local, nonacademic historians, they’re just gems.”

He encountered a lot resistance at first, spending much time trying to convince people that he was not a federal agent. But he said that patience and relentlessness are the hallmarks of a true sociologist.

“There’s an artistry to doing ethnography, to doing fieldwork,” he said. “If you truly love that and are engaged by that, then you stick with it, and over time you will make contacts and cultivate informants and people will embrace you and you’ll find out more than you would have dreamed possible.”

Cuneo’s ability to connect with people is being put to test these days as his latest book involves an examination of the transient subcultures that ride freight trains. To reach this group, he has ridden freight cars himself, the legality and safety of which he acknowledges is questionable.

“This is fringe behavior and at the same time it is connected in so many terrific ways to the soul of the nation,” he said. “Riding freight trains for a lot of them, especially for the younger breed of train tramps, is guerilla theater. In many respects, it’s a spiritual protest because they are asserting not only their economic and cultural disaffection and independence from the broader culture, but also their spiritual disaffection.”

Cuneo actually rode an open train car once in Yuma, Ariz., when he was 19 years old, and it was this ride that inspired the title of the book, Searching for Moon.

“Contemporary freight train riders feel this real kinship, and this real spiritual identification, not only with each other, but with the history of wandering people in the United States,” he said. “This is an act of resistance precisely against the homogenized tendencies of the greater culture.”

Christianity Today

By Agnieszka Tennant

Recently we’ve seen a rise in interest in exorcism. What makes it so appealing?

We live in a therapy-mad culture. There’s been an explosion over the past few decades of 12-step groups and therapeutic procedures of every imaginable description. Everyone, it seems, has been looking for some kind of an instant fix to problems. Exorcism fits in very nicely because it’s a kind of therapy that promises to be immediately and dramatically effective. And for many people, by the way, this is indeed the case. Demon expulsion may be therapeutically beneficial, at least in the short term. There’s no question about that. It’s a relatively inexpensive therapy that can be taken with dispatch. And it’s also, for the most part, morally exculpatory. It lets us off the hook.

“The devil made me do it”?

Yes, you know, my sexual infidelities, well, they’re not my fault; it’s the demons. Or my recurrent animosities toward co-workers? Well, I mean, obviously I’m demonized. We live in a culture where we’re encouraged to look for ways to get us off the moral hook and to find excuses. Indisputably, we are also, as a culture, very impressionable. And we are deeply influenced by the images and messages presented to us by the popular entertainment industry.

Have you witnessed an exorcism or a deliverance session in which you were convinced demons were really cast out?

I always go on site and interview people directly and take situations seriously. But still there’s so much I don’t know. I attended more than 50 exorcisms and never once did I walk away convinced that the person being exorcised was really demonized. I always thought that medical, cultural, and psychiatric explanations could have accounted for what was going on. But I might’ve been wrong. And people would often say to me, “But Michael, you should have been here last week. We had real demonic fireworks.”

You just missed it!

But that might be true. And some would say to me, “The reason you haven’t seen really powerful and dramatic symptoms of demonization [such as bodies levitating and so forth] is because you’re a writer, and the Devil is trying to disguise his activity and hide it from you.” I would find that strange but, nevertheless, it may be a possibility. A psychiatrist friend

[who helps to investigate potential exorcism cases for the Catholic Church]

told me that, in his estimation, 999 out of 1,000 claims of demonic possession are false claims. But he believes that there’s always that one out of 1,000 which isn’t false. I don’t think I ever happened across that one.

Does exorcism work?

I haven’t done the long-term, follow-up studies it would take to answer this question definitively. In the short term, exorcism can be quite helpful for certain people. It can provide relief, reinforce their sense of self, and help them overcome a feeling of demoralization or depression. I think exorcism can provide spiritual and emotional rejuvenation; it can embolden and empower people. I’m not suggesting this would be in every case and with all people. In some cases, demon expulsion can be nasty and detrimental. But I was at many exorcisms where I was convinced that at the very least nothing detrimental was happening. If anything, something therapeutically beneficial was taking place.

Could you describe it?

I sat in on quite a few private deliverances that were conducted by evangelical deliverance ministers. The majority of these were undertaken with pastoral adroitness and psychotherapeutic sensitivity. And these evangelical deliverance or exorcism ministers, for the most part, were not determined to find demons in the subject at all costs. There was real gentleness and a real care taken. I didn’t know if there were demons present – I’m not smart enough to figure that out since I don’t have any special gift of spiritual discernment – but at the very least I was convinced that nothing bad was taking place and the person receiving exorcism or deliverance was not harmed. I saw people who, in the short term, would clearly feel healed, uplifted, and empowered. And, following the casting out of their demons, they would overcome demoralization.

Dayton — The College

By Matthew Dewald

DARRELL MEASE of Stone County, Missouri, stole $200,000 in drugs from Lloyd Lawrence. So Lawrence put a bounty on Mease’s life. Acting first, Mease, on May 15, 1988, shot Lloyd Lawrence.

And he shot Lloyd’s wife, Frankie Lawrence.

And he shot Lloyd’s grandson, 19-year-old Willie Lawrence, a paraplegic.

Then at close range Mease blew off the tops of their heads. According to the autopsy report, “The cavities of the skulls were vacated of brain matter.”

Mease is the murderer in Michael Cuneo’s forthcoming book, The Pope and the Murderer.

By the time the pope, John Paul II, arrived in St. Louis in January 1999, Mease had been apprehended, convicted and sentenced to death – a sentence scheduled to be carried out soon after the pope’s arrival. The case attracted the attention of the pope, who met personally with Gov. Mel Carnahan, a Southern Baptist. The pope asked the governor to have mercy. The governor, out of respect for the pope, commuted Mease’s death sentence.

“This is the first time, as far as I know,” says Cuneo, who spent the fall 1999 term as a visiting distinguished professor in UD’s religious studies department, “in the history of the United States that a death sentence has been commuted through the direct intervention of a religious leader from outside the country.”

Cuneo has probed the relation of religion and culture in several books on topics including abortion, exorcism, and conservative and traditionalist Catholic dissent. In The Pope and the Murderer he will examine the story of Darrell Mease and its cultural, religious and political implications.

The pope continues to spread a message of life to the world. The governor, bidding for a seat in the U.S. senate, tries to convince voters he is not soft on crime. Missouri has had nine executions since Carnahan showed mercy to Mease, who now lives at Potosi Correctional Facility, 65 miles from St. Louis.

Mease, who was raised as a Pentecostal Christian, fell away from religion after returning from the Vietnam War. “He underwent a jailhouse conversion in 1989,” Cuneo says, “a reconversion to evangelical Christianity. Before the pope’s visit was announced, Darrell said he had a religious revelation: God told him his life would be spared.

“Now he claims God has spoken to him again, that it is only a matter of time until he walks out of prison a free man.”

The situation, Cuneo observes, “is very controversial.”

The Kansas City Star

By John Mark Eberhart

A FEW WEEKS AGO in these pages, I expressed my admiration for Michael Cuneo’s Almost Midnight: An American Story of Murder and Redemption.

Cuneo’s book chronicles the murderous fall of Darrell Mease, but also the strange twists that saved the Missouri Ozarks man from the death penalty when Pope John Paul II himself pleaded with the late Gov. Mel Carnahan to spare Mease’s life. Carnahan commuted Mease’s sentence to life in prison without possibility of parole; just a few months later, the governor was killed in a plane crash.

Cuneo will discuss his book at 7:30 p.m. Wednesday in Mabee Theater, Sedgwick Hall, on the campus of Rockhurst University, 54th and Troost. Rockhurst’s Thomas More Center for the Study of Catholic Thought and Culture and the Visiting Scholar Lecture Series are sponsors for the event. It’s a free lecture, but you do need to call and register. The number: (816) 501-4828.

The Sentinel (Stoke-on-Trent, UK)

On Health: An Interview with Michael W. Cuneo

CANADIAN-BORN author Michael Cuneo is acknowledged by many as the foremost authority on exorcism in North America. He teaches sociology and anthropology at Fordham University, New York City, and his previous books include The Smoke of Satan. His latest book is American Exorcism (Bantam, GBP 6.99), an inside look at the phenomenon of possession by demons.

How much sleep do you need?

“For years I’ve gotten by on four or five hours. But lately I’ve been feeling a bit drowsy in the late afternoon. The problem is I’ve grown accustomed to working until the wee hours, which is when I’m most productive.”

How do you feel first thing in the morning?

“On bad days, I’m a zombie crawling out of the grave. On good ones, a zombie on speed. An extra-large coffee from Dunkin’ Donuts and I’m back to being human.”

What exercise do you take?

“I used to play basketball with my two sons, but afterward my knees would be creaking and my hips burning. Now I try hitting the exercise bike as often as possible. I’m also in the habit of walking to 24-hour diners, which is where I do a lot of my writing late at night. But this is proving increasingly difficult, since all-night diners are fast disappearing in New York City. The city that doesn’t sleep? Maybe once, certainly not now.”

Are you careful about what you eat?

“Until last year I still had the diet of an immortal teenager: burgers, fries, the works. Now I’m pathetically careful – lots of salad, that sort of thing.”

Are you or have you ever been overweight?

“If I could lose about five pounds right now, I’d be lean, mean, and fighting trim.”

Do you take vitamin and mineral pills?

“I guzzle orange juice and eat apples by the bushel. Who needs pills.”

What foods can’t you bear to eat?

“I’m a real culinary primitive. I haven’t graduated beyond my working-class Toronto tastes. So no sushi, no gourmet pasta, nothing exotic.”

Do you drink or smoke too much?

“The drinking is completely under control. I smoke very moderately but only when I’m writing. I haven’t yet quit because – perversely – I’m reluctant to give the cultural Puritans the satisfaction.”

Have you ever been in hospital?

“Just twice. Once when I was 16 and hurt myself jumping off a freight train. Another time for a nose operation after one too many face-first collisions.”

Does your job affect your health?

“I spend a lot of time doing intensive field work, whether it’s sitting in on exorcisms, driving a cab, hopping freight trains, or hanging out with outlaws at cockfights in the Ozarks. All of this is potentially hazardous to my health.”

How often do you consult your doctor?

“A routine annual visit. Get the oil checked and make sure the points and plugs are okay.”

Do you suffer from stress?

“No, not unduly. Which doesn’t mean there aren’t stressful moments. Sometimes the demons unloosed upon the world put the demons in American Exorcism to shame.”

Are you happy with your body?

“It’s still functioning properly and so I’m thrilled with it.”

Toronto Star

By Michael McAteer

MEDIA PHOTOGRAPHS of hymn-singing anti-abortionists, kneeling in prayer, clutching rosary beads, have lent support to the notion that the anti-abortion movement is monolithic and homogeneous, actively supported by the institutional Roman Catholic Church with the unqualified blessing of its bishops.

Nothing could be further from the truth, Michael Cuneo concludes in his new book Catholics Against the Church (University of Toronto Press: $40 hardcover, $16.95 paperback).

In fact, Cuneo says, abortion, the very issue which is popularly supposed to evoke consensus among Catholics, provides the line of fracture for a widening ideological division within the Canadian Church.

Far from promoting consensus and unity within the Canadian Church, the movement is a battleground for competing ideas, a rallying point for those Catholics fearful of change and modernization within the wider culture and within Canadian Catholicism itself.

Cuneo says the Canadian anti-abortion movement is overwhelmingly Roman Catholic in composition but is scorned by the Canadian Catholic elite and scarcely tolerated by most bishops.

Moreover, despite its quintessential Catholicity, many movement activists regard the institutional Canadian Church with unconcealed contempt, and are at odds with the national bishops’ conference.

The anti-abortion protest, says Cuneo, has been embraced by a discontented segment of the Canadian laity as a crucible of faith at a time when the wider Church, including its bishops and professional elite, seem taken by other interests and absorbed by different passions.

“That the Canadian bishops are at best tepid in their support of the pro-life cause, and at worst traitors to it, has become an established belief within Catholic anti-abortion circles,” says Cuneo.

Cuneo’s “sociological and historical” study focuses on the anti-abortion protests in Toronto between 1969-1985.

He says the social make-up of the movement had by the 1970s produced a polarization between its professional elite who preferred to address abortion within a strictly civil rights frame of reference, and its flourishing grassroots supporters for whom anti-abortionism was inextricably a crusade against feminism, secularism, and the rise of moral permissiveness in Canadian society.

By the 1980s, says Cuneo, anti-abortionism for many activists had become a definite badge of Catholic authenticity and of countercultural spirituality, and any Catholic who did not wear this badge proudly was branded a traitor to the faith.

Cuneo says the relationship between the movement and the institutional Canadian Church has been plagued by bitterness and mutual estrangement.

“Particularly in Toronto,” he writes, “where movement passions burn hottest, militant Catholic activists have condemned mainstream Catholicism as apostate and have defined themselves as a holy remnant destined to conserve the flame of authentic faith at a time of spiritual decay and moral apathy.”

Cuneo says that although there is no reason to doubt that the Canadian bishops were, and still are, adamantly opposed to abortion, they very early adopted a hands-off policy towards the anti-abortion movement.

Even before the abortion debate heated up, Cuneo says the bishops clearly did not want to puncture the mood of ecumenical good feeling in Canada’s Christian community by resurrecting the spectre of triumphalism, and their statements on contraceptives and divorce were marked by deferential caution.

But he says that for some Catholic anti-abortionists that caution was a sign of capitulation to modernism and evidence of a real lack of commitment to authentic Catholic moral values.

Cuneo says that at a time when the anti-abortion movement was fighting to enshrine protection for the unborn in Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the apparent volte face by Toronto’s Cardinal Carter on his initial opposition to the charter was seen as a sign of betrayal.

Suzanne Scorsone, director of the Office of Catholic Family Life for the Toronto archdiocese, says some of Cuneo’s perceptions may have been valid at one time but substantial changes in the anti-abortion movement over the past few years have dated his research.

Scorsone said the gap between liberal and conservative Catholic wings has narrowed on the abortion issue in recent years and the influx of Protestant evangelicals into the movement has added a whole new dimension.

Scorsone said she has never met a bishop who wasn’t staunchly anti-abortion.

However, she said there are people in the anti-abortion movement who believe you are not really committed unless you are out on the sidewalk every day.

Scorsone said Canada’s bishops have made statement after statement on the abortion issue but “the only thing that would convince some folks they are principled is if they were on the National every other day. And they just can’t be.”

James Hughes, president of Campaign Life, agrees there is a perception within his organization that the bishops are not taking the lead in the anti-abortion campaign.

“We don’t look to the bishops to provide leadership . . . forget it,” Hughes said. “We are out there doing the very best we can and the very best we can hope for is that they annunciate clearly their Church’s position on the issue.”

Hughes said that when he first complained that his organization’s efforts appeared to be undermined by the national bishops’ conference, he was told to go seek the support of individual bishops rather than that of the national conference.

There is no question that the bishops are against abortion and that they are against it “firmly, strongly and completely,” says Frances Ryan, editor of the liberal Catholic New Times.

“But the bishops are also conscious they live in a pluralist society and a lot of the bishops have enough political savvy to know that they want to get the best deal they can and they know they are not going to get out-and-out prohibition of abortion. They are politically astute enough to try to lobby for what they can get.”

Conservative Catholic Anne Roche, of the Welland-Port Colborne Right-to-Life group, blames Canada’s bishops for the “mess we have.”

She says individual bishops are active in the anti-abortion movement and bishops, including Cardinal Carter, have come out with strong anti-abortion statements.

“But it is very difficult to forgive him about the way he [Carter] behaved over the charter . . . I don’t think Catholics are ever going to be able to forgive him,” she said.

Roche said militant right-to-lifers have been complaining for years and years that Canadian bishops as a body have been taking a back seat in the anti-abortion drive. “I think it is a disaster,” she said of the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops. “I believe this is the weakest national conference in the world. They seem to have no backbone . . . This is the most knee-jerk and quiescent episcopal conference I have ever read about.”