Contents

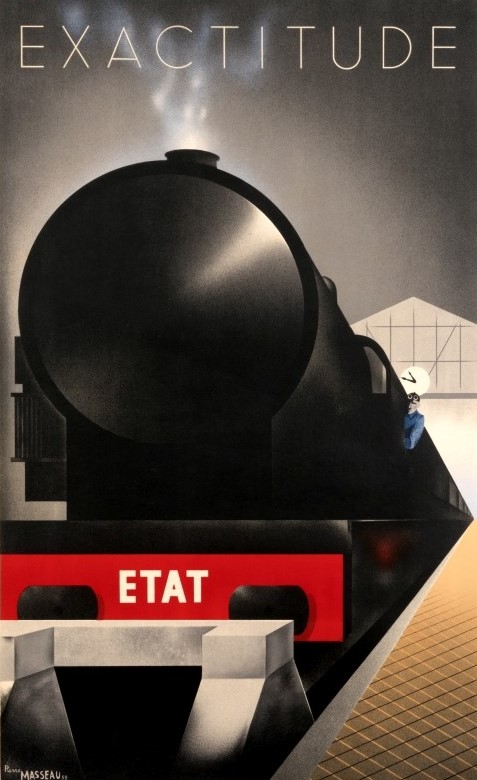

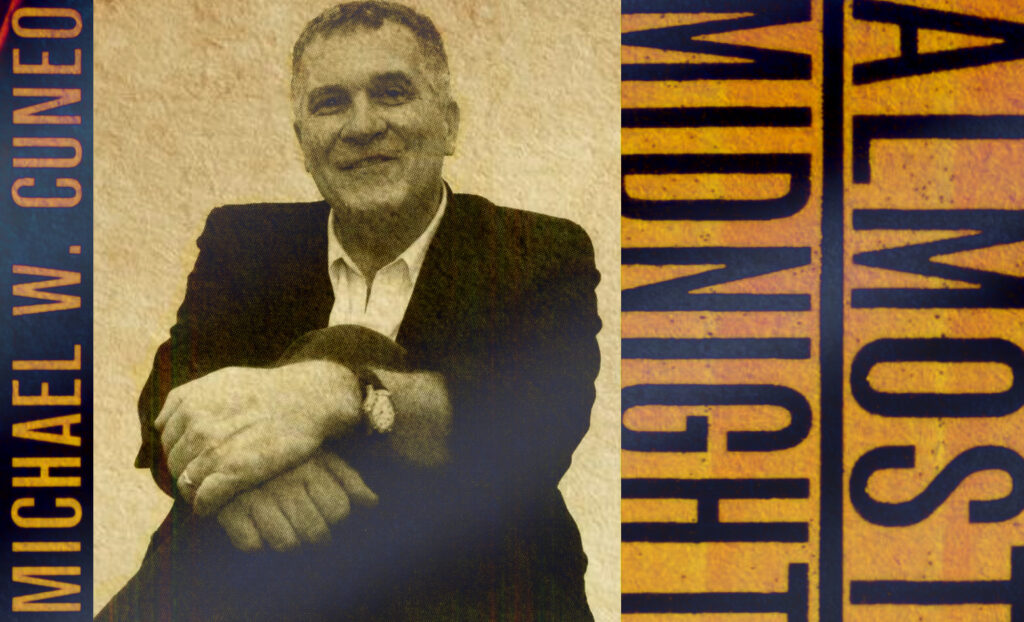

The Chronicle of Higher Education — Michael Cuneo: ‘Driving cab is the greatest training for everything I do’

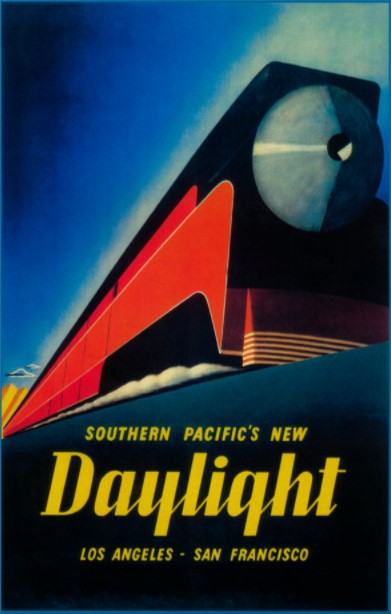

University of Dayton Quarterly — The Rails Beneath the Stars: Train-Tramping with Michael Cuneo

The Kansas City Star — Casting Out Demons: A Conversation with Michael Cuneo

Connecticut Magazine — Satan’s Playground

Las Vegas Weekly — Feeling Possessed? You’re Evidently Not Alone

Religion Watch — Interview with Author Michael W. Cuneo About Exorcisms

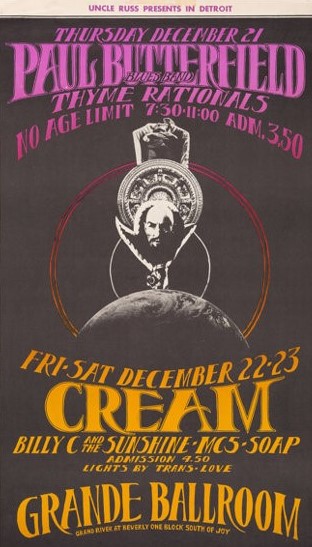

The Pitch (Kansas City) — Divine Intervention

Daily Camera (Boulder, Colorado) — Exorcisms, though rare, on the increase

U.S. Catholic — Is the Pope Catholic?: The Editors Interview Michael Cuneo

Read Magazine — Exorcism in American Culture: A Conversation with Michael Cuneo

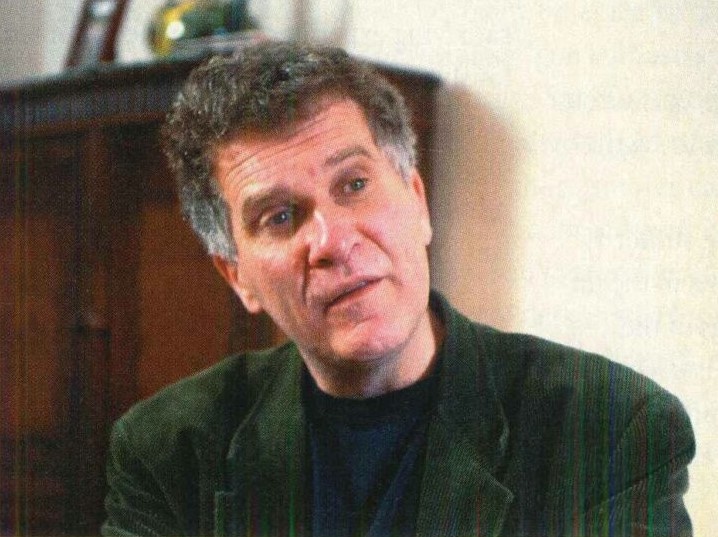

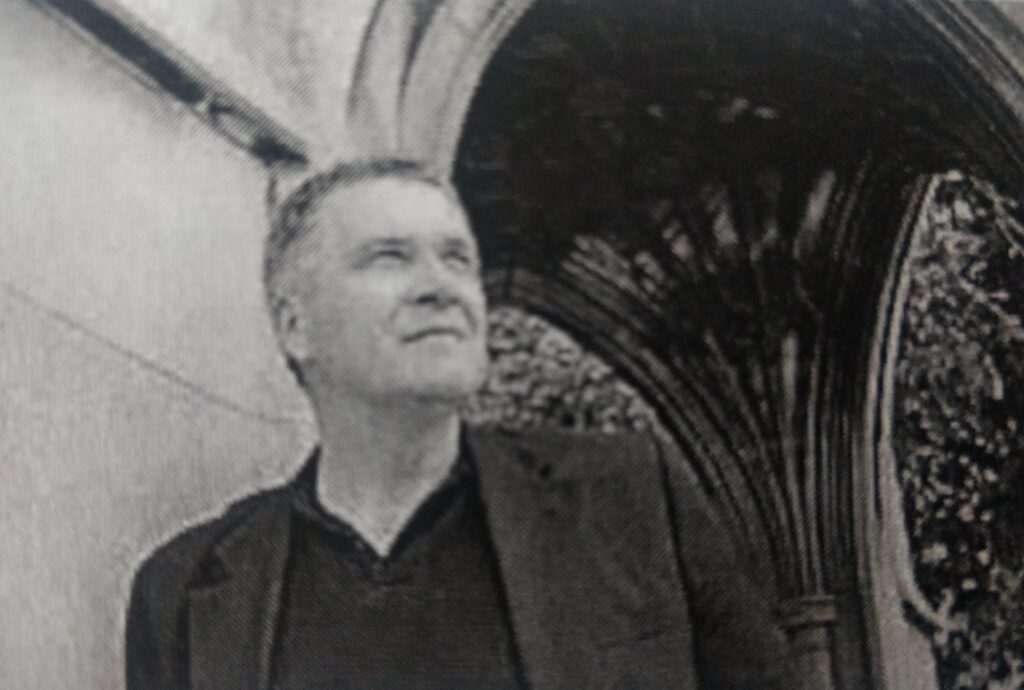

The Chronicle of Higher Education

Michael Cuneo: ‘Driving a Cab is the Greatest Training for Everything I Do’

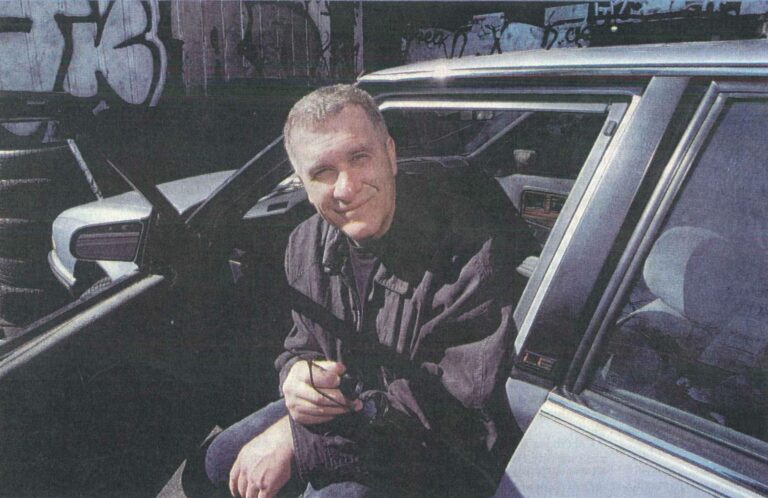

By Beth McMurtrie

ONE SUMMER EVENING in Illinois a few years ago, about 500 people filled the chapel at Wheaton College, eager to expel their demons of sexual perversity. A well-heeled collection of Episcopalians, Lutherans, Roman Catholics, and Presbyterians, they had traveled from across the country to attend a conference sponsored by Pastoral Care Ministries, an evangelical group based in Wheaton that had promised to cure them of homosexuality and other perceived ills.

An Episcopal minister took the stage and, arms outstretched, began praying quietly that people be delivered of their pain, confusion, and anger. Within minutes, the place was bedlam. Middle-aged women and men, dressed in casual weekend wear, began swearing and moaning. Some pounded their groins or simulated masturbation. Others fell to the floor wailing and speaking in tongues. Lay ministers and helpers moved among the congregants, uttering healing prayers.

About 45 minutes into the exorcism, the lead minister took control and declared an end to the proceedings. The deliverance, he said, would continue tomorrow. Instantly, people relaxed, collected themselves, and slowly filed out of the room, peacefully chatting with one another.

Michael W. Cuneo, an associate professor of sociology at Fordham University, stood in the back of the room, watching in stunned silence. “My goodness,” he thought to himself. “What have I just seen?”

What he had seen was his first group exorcism. That and more than 50 other exorcisms form the basis of his recent book, American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty (Doubleday). Mr. Cuneo, a Canadian who is intensely fascinated by American subcultures, spent more than a year crisscrossing the country to produce a vivid portrait of people who fervently believe that the devil is to blame for such problems as anger and alcoholism and—most common of all—their perceived sexual troubles like promiscuity, masturbation, and homosexuality.

Mr. Cuneo has seen exorcisms in which people vomit profusely into trash bins and others in which the possessed barely move. He has interviewed Roman Catholic priests ambivalent about the validity of claims of possession, and evangelical Protestants who see Satan around every corner. Several exorcists even claimed that Mr. Cuneo himself was afflicted and offered on-the-spot deliverance (he declined). He also met many compassionate ministers who, he argues, were sincere in their desire to help rid people of their troubles.

Yet, as he points out in his book, Mr. Cuneo never saw one spinning head, levitating body, or anything else that struck him as belonging to the realm of the paranormal. Although he stops short of saying that demons do not exist—his book, he says, is cultural commentary, not an effort to prove or disprove possession—it is clear from his writing and in conversation that he believes the demons haunting the people he has met are more personal than satanic.

SUPPLY AND DEMAND

The puzzle for Mr. Cuneo, as he began his research, was why people seek out exorcisms. The answer, he concluded after talking to dozens of Protestant “deliverance ministers,” Roman Catholic exorcists, and their clients, is popular culture.

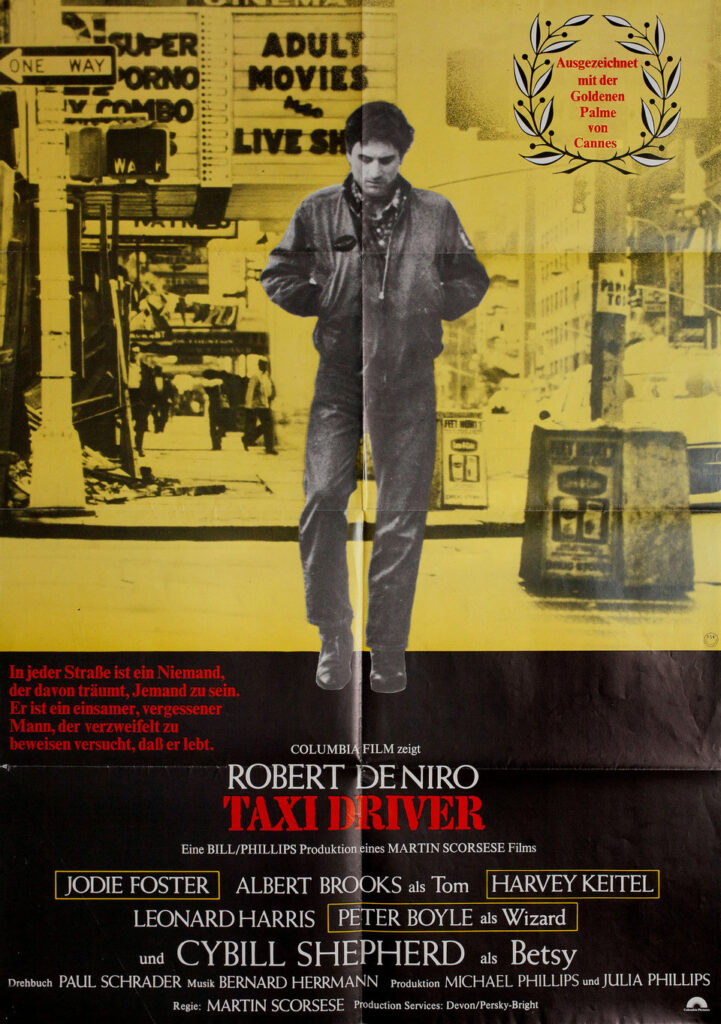

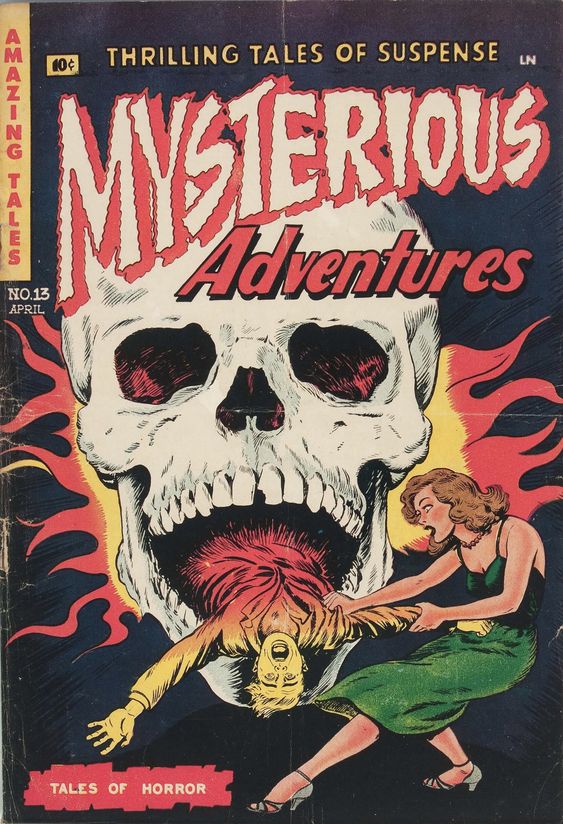

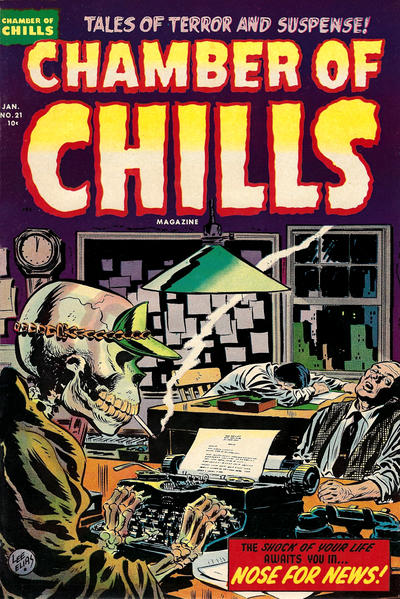

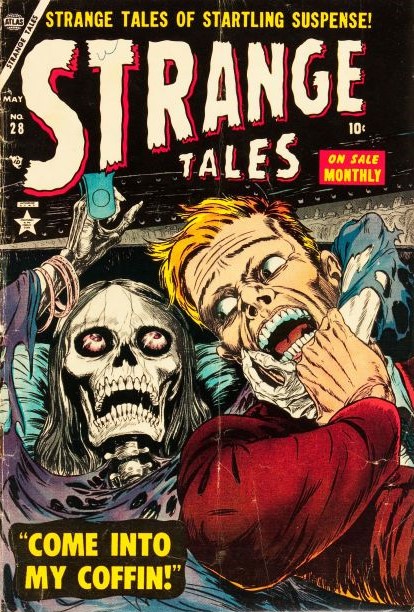

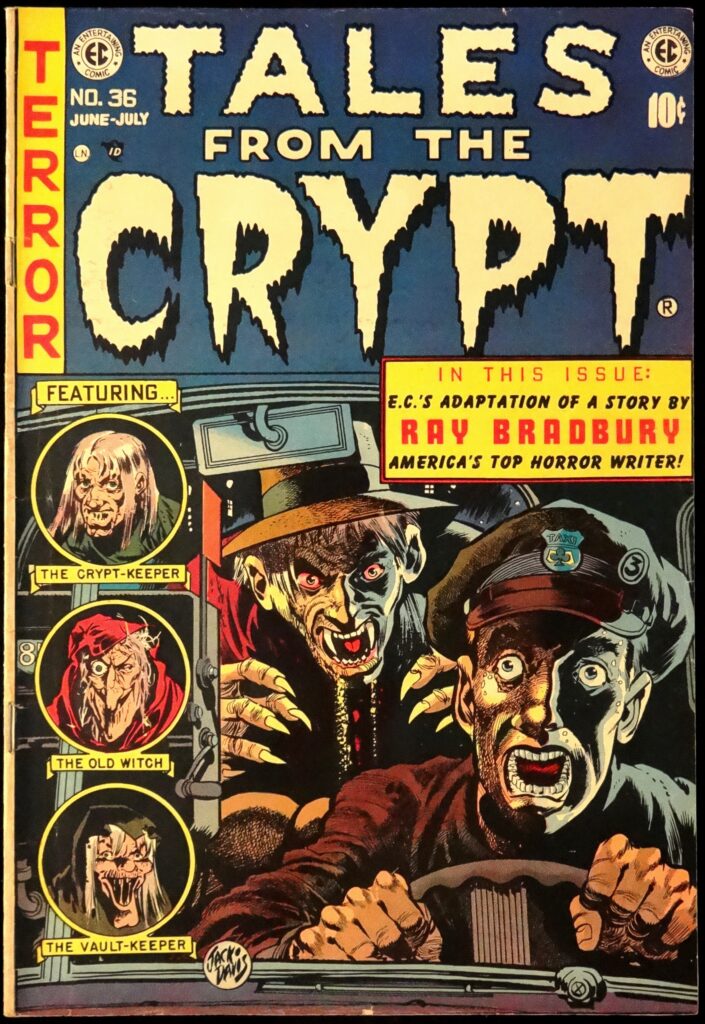

“It’s highly unlikely that there would have been such a fascination with exorcism, or such a demand for exorcism, if it weren’t for the popular entertainment industry itself promoting it,” he says over an Italian lunch in midtown Manhattan. A loquacious speaker with a warm, enthusiastic manner, Mr. Cuneo says that the 1973 release of the movie The Exorcist, along with a few bestselling books churned out in that decade on demonic possession, created an insatiable appetite for the subject.

“Everywhere you looked for a while there was this wall-to-wall grotesquerie on your television screen, in movie theaters, the publishing industry, daytime television,” he says. “I can’t imagine that people would think they were demonized if they didn’t see these images trumpeted about, paraded about, constantly before their eyes.”

Even today, Mr. Cuneo says, those who believe in possession frequently cite The Exorcist and another ground-breaking work, Malachi Martin’s 1976 book Hostage to the Devil, when explaining how demons work. Mr. Cuneo argues that another aspect of popular culture has also made people more open to the idea of demonic possession: the American pursuit of self-perfection. Given how eager we are to label and expel our imperfections, he asks, are exorcisms really any different from 12-step programs, alternative medicine, and New Age therapies?

“Deliverance promised new possibilities for the self, the possibility of an endlessly redeemed self, a self renewed and improved at a single stroke,” he writes. “Despite being cloaked in the time-orphaned language of demons and supernatural evil, deliverance was surprisingly at home in the brightly lit, fulfillment-on-demand culture of post- ‘60s America.”

According to American Exorcism, the Catholic church was unprepared for, and skeptical of, claims of possession. As a result, many people who feared they were demonized turned to charismatic and evangelical Protestants, who were more sympathetic to the idea. Although he offers no aggregate numbers—few scholars have even studied this subject—Mr. Cuneo maintains that the exorcism business remains alive and well. For example, among evangelical Protestants, no more than a handful of deliverance ministries existed before 1983, he says. By the early 1990s, there were upwards of 600.

In his book, Mr. Cuneo paints vivid portraits of the ministers and priests who perform exorcisms. Many are deeply conservative, seeing demonic possession as a result of the flaws of a liberal society in which drugs, sex, and feminism have opened people to evil spirits. Some of the possession cases he writes about border on the absurd, such as the minister who found himself drawn to pornographic magazines at an airport, only to conclude that the cabdriver who brought him there must have demonized him.

Others are disturbing, and lead Mr. Cuneo to wonder whether exorcisms distract people from their real problems. He notes, though, that the more sensitive ministers often encourage particularly troubled people to enter therapy to keep their demons at bay.

One young man whose exorcism he sat through appeared deeply confused over his sexual identity. He had a troubled childhood, compulsively masturbated, and was obsessed with violent sexual thoughts. After the ritual, the ministers suggested he seek psychotherapy.

One of the ministers profiled in American Exorcism, Francis MacNutt, head of Christian Healing Ministries, says that Mr. Cuneo accurately portrayed both the good and bad aspects of his field. “Often,” he says of some other ministers, “they overextend deliverance ministry and don’t do inner healing of the emotions, and psychological counseling.” The Harvard-educated former priest believes that Mr. Cuneo overstated the influence of The Exorcist, but agrees that the therapeutic movement has made people more open to deliverance.

His one disappointment: that Mr. Cuneo seemed to remain a skeptic. “I think he was trying to be open,” he says, “but whatever it was he saw didn’t convince him.”

Mr. Cuneo says that while he saw no evidence of demons, he found the vast majority of the priests and ministers he met to be caring and sincere people. Most accept no money for their work. And although some believe firmly in the physical release of demons—vomiting and all—many prefer to take a calmer, more pastoral approach in conducting exorcisms.

He was also surprised by the number of people who claimed that exorcism works. After the mass deliverance he witnessed at Wheaton, “people would tell me they felt at peace,” he says. “Some folks said they felt more hopeful and peaceful than they had in a long time.”

LIFE ON THE MARGINS

Mr. Cuneo has long been drawn to the alienated and offbeat segments of American society. His previous book, The Smoke of Satan: Conservative and Traditionalist Dissent in Contemporary American Catholicism (Oxford University Press) profiled a number of separatist groups that had broken away from the church.

His next work, provisionally titled “Passin’ Through” (Broadway/Random House), is about a triple murder involving backwoods methamphetamine manufacturers in the Missouri Ozarks.

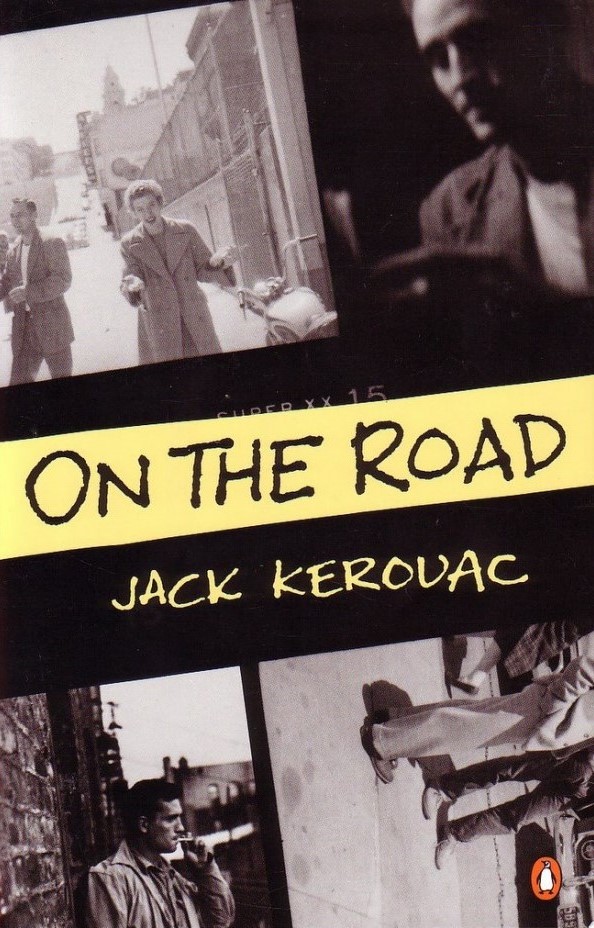

Mr. Cuneo has followed his own beat as well. The son of a cabdriver and a teacher’s assistant, he grew up in a blue-collar section of Toronto. At 20, he set out on a two-year tour of the United States, hitchhiking around the country and supporting himself with odd jobs. He delivered handbills in San Francisco and cleaned cargo boats in New Orleans.

After returning to Canada, he enrolled at the University of Toronto, got married, had a child, dropped out, and started driving a cab to support his growing family. Many fares later, he returned to his studies at Toronto, eventually earning his doctorate in the sociology and anthropology of religion at age 34.

Cabdriving is central to Mr. Cuneo’s identity. He even drove a cab his first year teaching at Fordham. That experience has informed his research, he says: Being friendly, down-to-earth, and willing to listen to his fares helped him when it came time to track down and gain access to generally untrusting people, be they Catholic separatists, deliverance ministers, or Ozark outlaws. “Driving cab is the greatest training for everything I do,” he says.

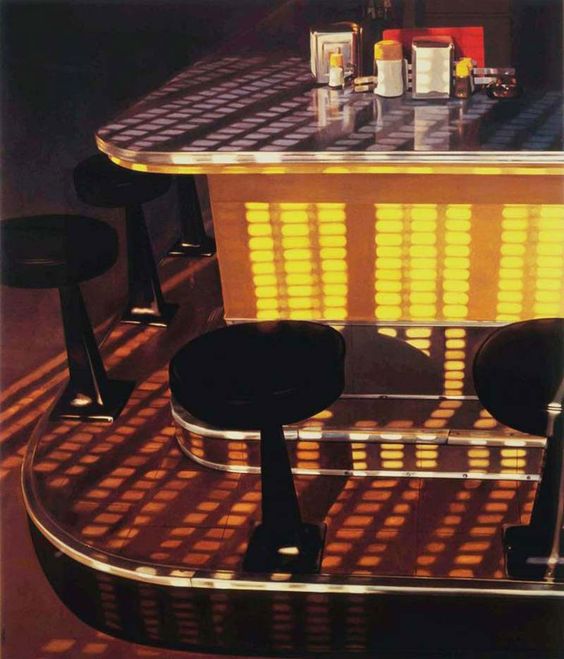

The fact is, Mr. Cuneo loves the road, and everything that comes with it. In 1992, after he finished his first year at Fordham, he and his wife decided they would rather raise their kids in Toronto. Every weekend he makes the 510-mile commute back home in his 1989 Pontiac Bonneville, which, he is proud to say, has 290,000 miles on it.

He keeps no apartment in New York. Instead, he stays at a different cheap motel every week. “I am, in terms of my tastes, a very primitive guy,” he says with one of his frequent broad smiles. “I like to hang out at Waffle Houses at the counter. A grilled cheese and coffee—that’s ecstasy, that’s heaven to me.”

When he is conducting research, he practically lives on the road. His books begin on a tip, he says, then he jumps in his car to do “reconnaissance.” The idea for “Passin’ Through” came from a newspaper article. He spent a week in the Ozarks, decided it was worth a book, then spent the next 11 months driving to Missouri to talk to the drug dealers, methamphetamine-lab operators, police officers, and lawyers who played a part in the case.

A JOURNALIST’S APPROACH

Although many of the characters that populate his books live on the margins of society, Mr. Cuneo believes they offer lessons about the larger culture. For example, both The Smoke of Satan and American Exorcism, he argues, reflect the timeless American pursuit of moral perfection. “This quest for utopia is still very much alive, and it assumes very interesting guises,” he says.

William D. Dinges, an associate professor of religion at Catholic University of America who has reviewed The Smoke of Satan, agrees. Catholic separatist groups, which broke away following major church reforms in the mid-1960s, reflect the church’s difficulties in adapting to a modern, more secular world. “These more fringe groups, they are canaries in the cultural mine,” he says.

Both Smoke of Satan and American Exorcism have received positive notices from reviewers and scholars. A number of academics have praised Mr. Cuneo’s empathy for his subjects, and his ability to write in a way that is understandable to the general public.

Not all scholars feel his journalistic style hits the right notes, however. R. Scott Appleby, a history professor at the University of Notre Dame who has written extensively about religion in the United States, calls American Exorcism “engaging” but says it doesn’t venture much beyond the anecdotal. He’d like to see more hard data to back up Mr. Cuneo’s claims, and a stronger theoretical framework to provide context to what he witnessed.

But Bradford J. Verter, a visiting assistant professor of religion at Williams College who uses Mr. Cuneo’s two most recent books in his class, disagrees that there is anything lacking in American Exorcism. “The theoretical issues are not as deeply articulated as they would be if he were writing for a narrow audience, but they’re no less powerful for that,” he says. “Who knows, writing for a broader audience may get people interested in the subject.”

Mr. Cuneo is unapologetic about his approach. “There’s no question that American Exorcism is a cultural critique, and it’s intended to be that,” he says. “I’m not interested in writing a traditional scholarly book in that sense. I’m interested in vigorous writing.”

His next book after “Passin’ Through,” tentatively titled “Midnight Motel,” looks at the life of transients in the United States. He has also done preliminary research for books on gambling, and gypsy-cab drivers in the Bronx and Harlem. He loves Americana, he says, the colorful lives of the down and out, the quirky lingo people use, their resistance to the homogenizing forces that make so many cities and towns indistinguishable from one another.

“These are the most real people in the United States,” he says. “These are the people I love the most, the people I most appreciate being around. So to be able to write about their lives and the local subcultures is an honor, and a privilege, for me.”

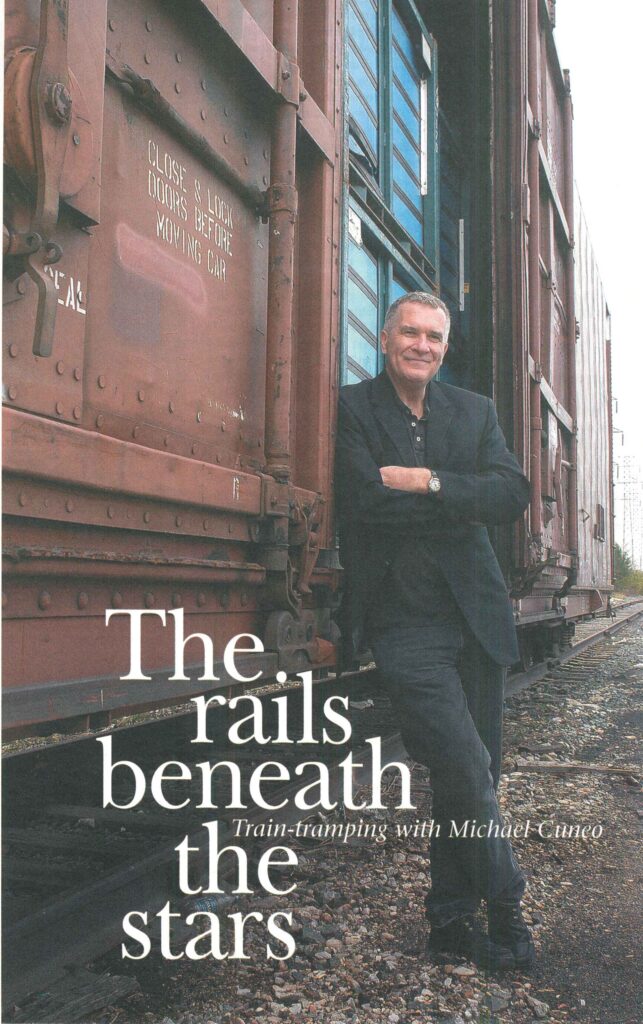

University of Dayton Quarterly

By Matthew Dewald

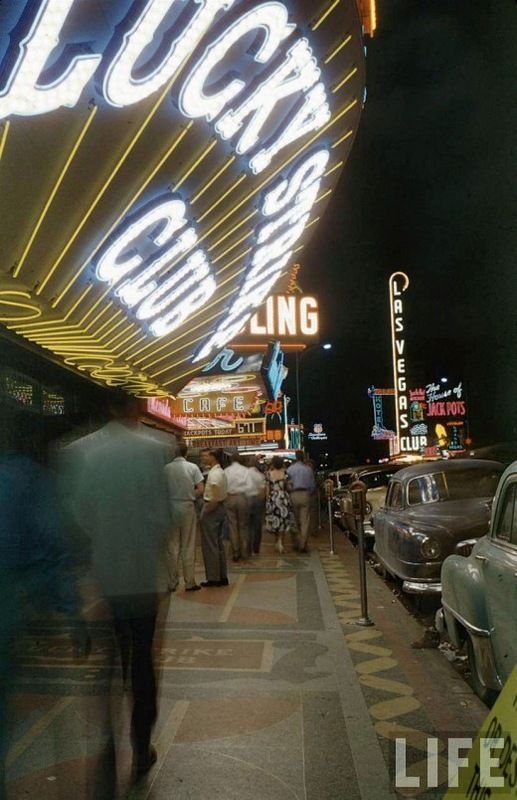

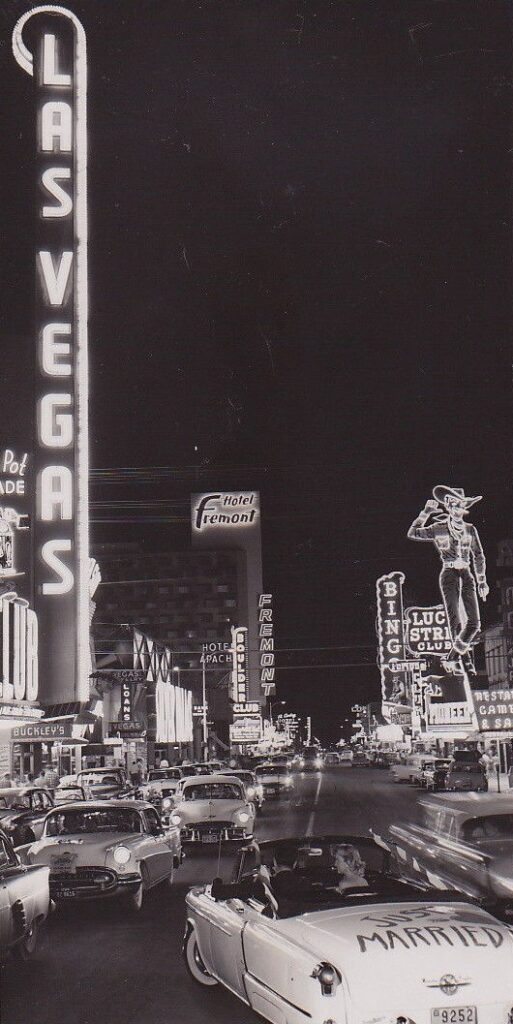

IN A RAILYARD near Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia, a reckless train tramper named Tommy helped Michael Cuneo hop the first freight car of a seven-week journey that would take him across Pennsylvania, through the Midwest to Oregon, California and finally Las Vegas. Cuneo snuck onto that train in the summer of 2004 to explore first-hand the phenomenon of train tramping – illegally riding freight cars on railways across the country.

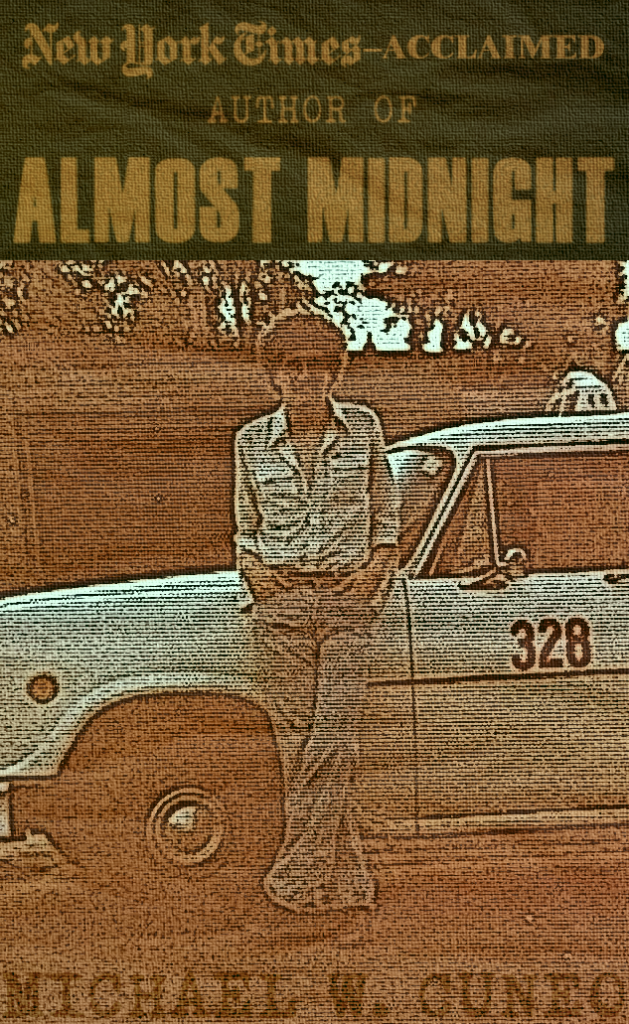

Searching for Moon: Train-Tramping in the United States, his account of his experience and the subculture he discovered, will be the third of what he calls his “Dayton books,” books he has done significant work on while at UD during his current and previous visiting professor appointments in the department of religious studies. His earlier Dayton books include American Exorcism and Almost Midnight: An American Story of Murder and Redemption, the true story of a triple murder in the Missouri Ozarks and Pope John Paul II’s request to the Missouri governor that the convicted man’s death sentence be commuted to life in prison.

Why on earth did you do this?

When I was 19 years old, I spent two years touring around Canada, the U.S. and northern Mexico. I started out with $10 in my pocket. I was with a friend from Toronto, and we would find work in different places.

Mainly we hitchhiked but one time in Yuma, Ariz., we went into the railyards and met three guys. Two of them were Vietnam vets, Trigger and Bob. And there was a third guy, Moon-Face, whom the others simply called Moon. He was an exceedingly charming guy. At the time he seemed to me kind of an old-timer, but I’d only just turned 19. It’s possible that he was in his mid-30s.

During the course of the evening, we discovered that Trigger and Bob were very dangerous guys, desperate guys. We wound up hopping a train with them against our will, a big Southern Pacific grainer or hopper car.

It was in the middle of winter – this was January 1973 during the height of the Watergate scandal – we wound up going through the desert, and we had no idea where we were headed. It was freezing cold. We thought we might perish just from the elements, plus we were terrified because Trigger was threatening us with a gun.

In the middle of the night, Trigger and Bob threw this Moon character – who was more of the traditional old-style train tramp, train hobo – off the train while we were going top speed. He was probably killed on impact or was sliced to death by the wheels. Even if he survived initially, he almost certainly would’ve died from exposure in that nighttime desert. It was terrifying.

And so there we were, stuck, and I saw everything happen. I was sitting on the hopper platform with my sleeping bag draped over me. There were these three guys in front of me: Trigger, Bob and Moon. I saw them throw Moon off the train. It was surreal, and I was completely naïve, a total Canadian innocent.

My first response was to start counting the guys in front of me. “One, two . . . uh, let me start again. One, two . . .”

I wanted to get to three but I couldn’t. I could only get to two, and I was finally able to say with certainty that this had really happened.

We jumped off the train when these guys dozed off. It slowed down going into a railroad yard. We ran out of the yard up to this little railroad café, and I asked the waitress, “Could you please tell us where we are?” and she named the street intersection.

I said, “No, could you please tell us what town we’re in?”

She said, “You’re in Phoenix, Arizona.”

This Moon guy has stayed with me down the years. I decided some time ago that I must do some research on this. That’s why I call the projected book Searching for Moon: Train-Tramping in the United States, because my research is a kind of metaphorical search for this old-time train hobo that I saw get thrown off this Southern Pacific grainer platform when I was 19 years old. It’s also a metaphorical search for a lost, possibly eclipsed and clearly imperiled subculture in American cultural lore.

Can you describe Tommy?

Tommy taught me a great deal. Tommy is a guy from Michigan. When I went out riding with him, he was 26 and had been practically living on trains for about 11 straight years. Trains were his life. He loved trains. He knew so much about them. He knew all the crew change spots in the U.S. He knew how to read a moving freight train for potentially rideable berths, and he knew all the railyards that were “hot,” or where you stood a good chance of getting arrested.

He was absolutely reckless, completely unreliable, completely irresponsible. Tommy did way too many drugs, drank way too much alcohol, but he was also in his very own rough-hewn manner completely charming, and I retain great affection for the guy.

What did you bring with you?

A backpack, a standard sleeping bag and an extra pair of jeans (a real luxury), underwear, socks, some T-shirts and a jacket. I had a stainless-steel thermos for my coffee, a canteen for water; and I had a plastic ground sheet which doubled as a rain poncho. That is absolutely crucial because inevitably you find yourself stuck on some train completely exposed to the elements.

I brought six notebooks for my field notes, and I brought a knife because you cannot be out there without some measure of protection. I’m a nonviolent guy, but that knife saved me from a number of altercations. So I brought the knife and a pair of work boots, a pair of work gloves and a flashlight, and that was about it.

What about credit cards? Cell phone?

No, no, no. If you’re going to do the research, then you do it authentically. I wanted to experience the lifestyle, and I also wanted to put myself into situations where I’d be meeting people who were living the lifestyle, and so that’s what I did.

I got to meet a lot of people, and a lot of them I was able to meet initially through Tommy simply because he knows so many people out there, and he knows where they are likely to be camped out there beside tracks. He knows where all the catch-out spots are. Without him I wouldn’t know any of this stuff.

Can you explain what you mean by “catch-out” spot?

Catch-out spots are regarded as sacred territory by train riders. These are strategically located places where train tramps can hang out, hide out, camp, sleep, and at the same time they can be waiting for a train to hop. Train riders know them very well, and they have a strong sense of proprietorship – these are their spots. There’s a sort of intergenerational continuity to them. They believe that these same catch-out spots have been used throughout the decades by train riders. They feel kinship with people who have ridden trains before them.

What happened at the catch-out in Milwaukee?

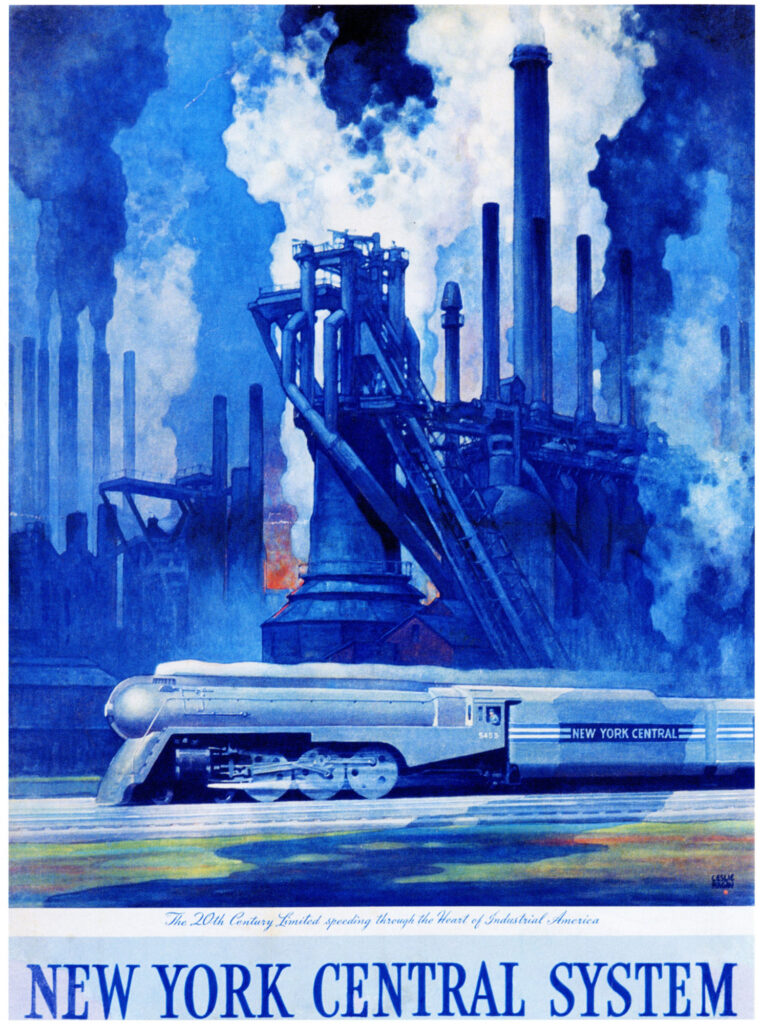

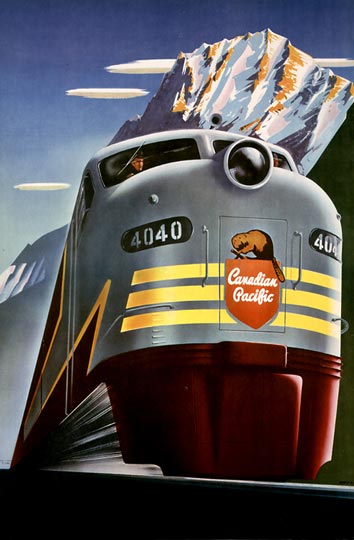

We were waiting for a Canadian Pacific freight to take us to the twin cities, Minneapolis-St. Paul. We were at a train-riders’ catch-out spot, but to Tommy’s chagrin it had been taken over by a very dangerous group of crack dealers. These guys were very menacing and armed and dangerous, and they didn’t want us there.

Tommy was, of course, very defiant and said, “This is for train riders.”

We were there for over two days, and it was vastly contentious. Eventually we got to the point where it was very, very nasty, and they were very seriously threatening our lives.

I was encouraging Tommy, “We gotta go. We gotta get out of here.”

Tommy’s attitude was, “Absolutely not. This is our turf. This is for train-riders. We never abandon a catch-out spot. We will fight for this to the death.”

I didn’t want to die for this squalid piece of land. It was on a ledge under a bridge. You took some rickety old ladder onto this garbage-strewn dirt ledge underneath a bridge close to an interstate. I wanted to abandon it. I thought that our lives were at risk. Not only did I have to trust my instincts there, but I couldn’t trust Tommy’s because Tommy was addled by the crack he had been smoking, so he was being very stubborn.

But I could also understand his point. This is sacred turf for him. His attitude was that when you ride together on the trains you should die together to save that turf. I was committed to living the lifestyle but not to the point where I wanted to die.

Finally, there was a rupture in our relationship because I thought that he was being foolish risking our lives for the sake of this catch-out spot, and he thought that I wasn’t being sufficiently respectful of the catch-out spot. We parted ways a couple of weeks later, in Iowa, and I rode the rest of the way mostly on my own.

Getting on and off the trains is dangerous, of course, but is actually riding trains comfortable?

Riding the trains is inherently unsafe and enormously uncomfortable. The freight train is not a cushioned ride. It’s jerking, banging, thrashing. At the very best, from sheer exhaustion I would fall into a kind of fitful sleep for 10 or 12 minutes and wake up with another jolt.

Mostly I rode hoppers and container cars. The smoothest ride is in a boxcar. There aren’t nearly as many open boxcars out there as once was the case. The only way to get into a boxcar is if it is stopped. The smartest and most experienced train riders would never try to hop a moving boxcar, so you have to find one just sitting there.

If you’re able to work that out, the most important thing is to secure the open doors. You get some railroad spikes or pieces of wood, which you jam into the doors so that they don’t slam shut, because there is no way to open the doors from the inside. You’ll die in there of heat prostration or thirst or starvation.

If you’re going to sleep in a boxcar, you have to make sure you are positioned so that when there are sudden jolts or stops, you are not going to crush your head.

Who are today’s train trampers?

You still meet up with old-style train tramps going around the country for work. Those people are usually male, 20-35 years old.

Most people I met were young, wounded and abandoned. Many of them were very articulate but extremely disaffected with mainstream society in the U.S. I’m talking about kids 17 to 25, and they’re rebels.

There’s a whole sort of lost generation of these kamikaze train tramp kids in the U.S. They constitute an almost completely invisible population. They’re filthy, ragged. Some of them are of middle- or upper-middle class background. Some have had at least a bit of college education. Many I met are far more articulate than your typical undergraduate, far better read, but they’re seriously disaffected with everything about conventional society.

So they’re radical dropouts, and riding trains for these kids is a form of guerrilla theater, a subversive political act. Not only that, a lot of these kids feel a deep spiritual kinship with train riders who have come before them, and an intellectual affinity with the tradition of train tramping and hoboing in the U.S. A lot of these kids are able to talk with you about the Wobblies [a nickname for members of the Industrial Workers of the World, an international workers’ union most active in the early 20th century]. They know this stuff and talk to you about the old-time hobos from the Depression era. They know this stuff, care about it, and see themselves as part of this very long and precious lineage in the U.S.

I didn’t expect to meet as many young women as I did. That was a surprise. They very rarely travel alone. There are usually a couple of guys with them.

There are also desperadoes out there, people on the run from the law and operating in the underbelly of American culture. So it’s a very dangerous lifestyle. You can count on having run-ins with some really dangerous people. And the trains themselves are unforgiving and dangerous.

How in the world did you convince your wife and children to let you do this?

The kids mostly thought it was very cool, and they were very supportive. Margaret took quite a bit more convincing, but she knows me. She knows my heart, and she knew I would come home.

She did ask two things of me. She said, “Try to make a point whenever possible of getting on and off trains when they’re not moving.”

She also said, “Michael, when you are out there inevitably there will be altercations. Do everything possible to run away, to escape them.

Did you have any contact with her during your seven-week experience?

Yes, Margaret had me memorize a 27-digit telephone card number, so whenever possible I’d find a payphone and tell my family where I was and assure them that I was safe.

How does your research fit in with your appointment as a visiting professor of religious studies, of all departments?

Well, this is interesting because the last time I was here a couple of years ago I did research for a book called Almost Midnight. On the surface you would think, “What did this have to do with religious studies?” because it’s a book that looks at a triple homicide in the Missouri Ozarks. But it’s got plenty to do with religion. Pentecostalism figures very prominently in the story. Not only that, but Pope John Paul II wound up coming to Missouri and making a special appeal to Governor Mel Carnahan to commute the death sentence of the guy who’d been convicted of this brutal triple homicide. The book brings in the pope and all of the religious and spiritual implications of the commutation, and also the impact of religion on the culture of southwest Missouri. So the book on one level is about a triple homicide, which seems not to have much to do with religion. Then you find out that it has everything to do with religion.

Same here with train tramping. You think, “My goodness, what does train tramping have to do with religion?” but the whole research project is fraught with religious significance. The first and the most important thing we should do as we study religion in the U.S. is to study explicitly institutionalized religion, which is religion found in churches, schools and homes. That should be given the highest priority. After that, I think we should explore noninstitutional, cultural forms of religion, looking at different secular mythologies.

Train tramping is one of the most precious, significant mythologies in the U.S. Think of the themes it conjures up: freedom, defiance, wanderlust. These are spiritual themes that are pivotal to the American cultural legacy. They’re written into the American soul.

By describing train tramping as you do, do you feel there is a danger that you’re romanticizing in any way what is a very hard lifestyle?

Well, I try to depict train tramps such as Tommy honestly. On the one hand, I have immense admiration and affection for Tommy. I hold him in high esteem.

[But] he is a tough guy to hang out with. He’s definitely a daredevil. He does put you in hazardous situations, but I have respect for him. It’s funny: he’s a real sex star out there. Train-hopping girls love Tommy. But I have a big concern about how long he can keep going with that lifestyle.

I talk about the tough aspects of the life, and yet it is in some respects a romantic life. You hop a train at one in the morning, and you’re all by yourself. It starts moving roughly in the direction you hope, shaking and rocketing, and you start picking up that wind and the stars are out – it’s so romantic and you do feel a spiritual kinship with everyone else who’s done that. It might sound trite, yet there’s something that happens to you when you’re out there.

This is why it appeals to a lot of these train kids. It’s so radically countercultural because when you get on one of these freight trains you are really removing yourself physically, psychologically, emotionally, and, in a profound sense, spiritually from the mainstream culture.

The interesting thing is that the mainstream culture loves it. Everywhere I went, I met people who were thrilled to find out I was doing this. They’d give me food, coffee, a place to wash up. I think that ordinary Americans also feel this sense of romance, this sense of the spiritual symbolism of riding the rails. And the lifestyle fascinates them.

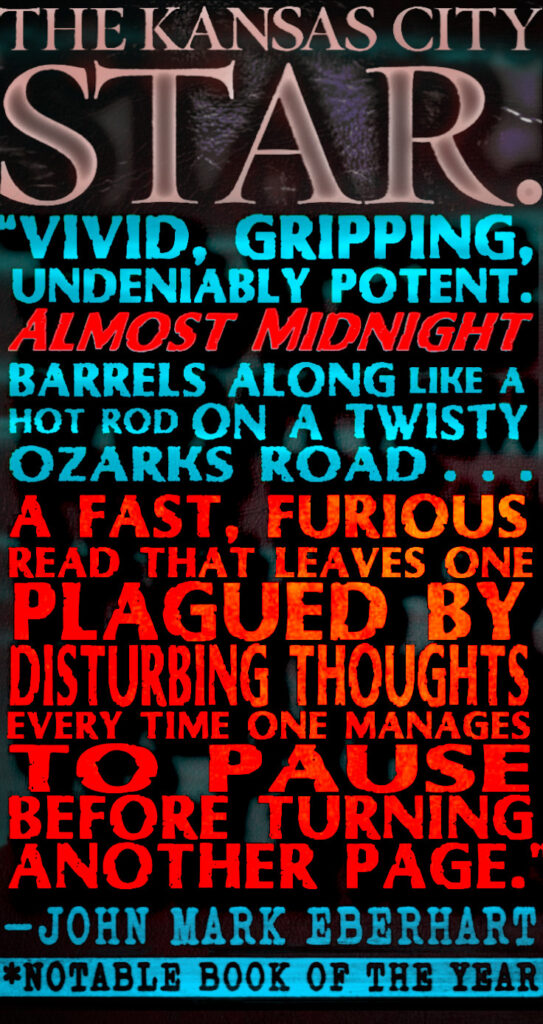

The Kansas City Star

Casting Out Demons: A Conversation with Michael Cuneo

By Shelvia Dancy – Religion News Service

Michael Cuneo has seen grown women and men thrashing wildly on the floor in sandbox-worthy tantrums.

He’s seen an insurance executive on his knees and screaming full-throttle in an auditorium packed with similarly anguished souls. “Models of middle-class decorum” convulsing, spitting and screaming obscenities. A pastor barking and cursing unashamedly.

All raising hell to banish their inner demons.

New therapy? Hardly. It’s exorcism.

“I think exorcisms are being performed to a much greater extent than the public imagines,” said Cuneo, a front-row witness himself to more than 50 exorcisms and author of American Exorcism (Doubleday).

In his book Cuneo argues that not until Linda Blair’s jolting portrayal of demonic possession in the 1973 horror classic “The Exorcist” did the topic slip onstage. Before then exorcism barely roused notice, much less registered on the national consciousness, he said.

“There were some charismatics and Pentecostals performing exorcisms, but it was not a big deal; even the major Pentecostal denomination in the U.S. was a bit embarrassed about it,” said Cuneo. “Exorcism ministries were rare, and there was marginal public interest at best.”

But the film turned heads, and a succession of copycat movies plus nationwide allegations of satanic child abuse at day-care centers in the 1980s stoked popular interest.

“By the end of the ‘80s it was hard to watch daytime TV without encountering this stuff,” Cuneo said. “Geraldo, Oprah, Donohue. Even Ms. Magazine had a completely uncritical feature on the topic. Many Americans – and not just evangelicals – believed that there was a vast satanic conspiracy in the land and Satanists were abducting children off the street and subjecting them to horrific ritual abuse.”

“Claims of satanic abduction and abuse were often taken at face value,” he went on. “Which really galvanized popular interest in exorcism. There was an explosion of exorcism ministries throughout the United States.”

The popularity is still thriving, Cuneo said, pointing to the frenzy that greeted the recent release of the director’s cut of “The Exorcist” – and the frenzy likely to greet the original’s prequel, which will start filming next year.

“For two weeks there was wall-to-wall coverage, and it became a sensation all over again – the popular media could not get enough of it,” he said. “I fielded dozens of calls daily for a fortnight.”

Indeed, Hollywood has been a wet nurse to much of the public’s fascination with exorcism, Cuneo said.

“I am convinced that exorcism would be very rarely performed today were it not for the popular entertainment industry,” he said. “The media has given the ritual – especially the Roman Catholic variety – so much coverage over the past 40 years. This has played a huge role in creating demand for it.”

Many who claim to be possessed “model their behavior on depictions of possession in the popular media,” Cuneo said.

“It might sound glib, but I was pretty certain that most of the presumed demoniacs I saw were acting out, taking their cues from what they had seen on TV and the silver screen and from things they had read,” he said. “People need an idea of how you’re supposed to behave during an exorcism, and they tend to get that from popular entertainment.”

Snagging an exorcism these days depends on the kind you’ll settle for. It’s extremely difficult to obtain an officially sanctioned Roman Catholic exorcism but there are plenty of other options.

“It’s relatively easy to get a Pentecostal or charismatic exorcism (or deliverance),” Cuneo said. “Or an unofficial Catholic procedure performed by a traditionalist priest-exorcist.”

Exorcisms aren’t always a one-size-fits-all procedure – you can take your pick of “specialized exorcism ministries.”

“There are ministries that specialize in highly specific areas, such as expelling demons of sexual perversion,” Cuneo said. “You can also get rid of demons that have been inherited through the family line – this is a real growth area.”

Because they “tend to be morally exculpatory,” he said, exorcisms can be wonderfully helpful.

“People are looking for causes for the problems they’re experiencing, and the idea of demonic possession is very appealing,” he said. “Exorcisms let us off the hook morally.”

They also are “the cheapest form of therapy,” he said. “Exorcists usually don’t charge for their services.”

Cuneo was impressed by the sincerity of many exorcists he met.

“Did I encounter some flakes, some crackpots, some people who were quite possibly doing harm? Yes. But they were the exception,” he said. “Most struck me as very earnest and dedicated.”

Though demonic possession is a subject that makes some skittish, believers are quick to point out that theirs is an ancient tradition.

“They say that Jesus himself performed exorcisms,” Cuneo said. “They insist that this is a necessary and legitimate ministry that has long been suppressed and is now undergoing renewal. For Christians who believe they’re living in dangerous times – satanic times – this kind of ministry affords another opportunity to emulate Jesus and the apostles.”

Connecticut Magazine

Satan’s Playground

With evil so much in the news these days, it’s no wonder that exorcisms are on the rise

By Alan Bisbort

[excerpted]

THE NEW WAVE of exorcisms come in every shape and size, and most bear little resemblance to the familiar depiction of them in the book and film version of William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist (1973). They have been taken up most notably by evangelical Protestants, who in New England include mainstream denominations like Lutherans and Episcopalians. In the South and Midwest, Pentecostal “deliverance” ministries are flourishing, and exorcisms are also now performed by rabbis and Buddhist monks. They take place as often in the homes of the possessed as they do in religious sanctuaries.

Most surprisingly, perhaps, exorcisms have even been accepted by a few mental-health-care professionals as a safe, quick and effective means of expelling “demons of addiction galore: alcohol, cigarettes, bitterness, anger, despair,” says Michael Cuneo, a professor of anthropology at Fordham University and author of American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty. “But probably half of all expulsions are for demons of sex.”

After spending two years on the road researching his subject, Cuneo, a transplanted Canadian with a sunny disposition, calls exorcism “a flourishing industry.”

“Some time ago sources told me, ‘Michael, did you realize that exorcisms are being widely performed today?’” Cuneo told a recent gathering at R.J. Julia’s Booksellers in Madison. “My curiosity was piqued, I was between semesters and book projects, so I gassed up my Bonneville and hit the road to see for myself. I toured the United States and had absolutely no difficulty uncovering exorcisms of every imaginable stripe. There’s even a pocket of exorcism activity going on within minutes of this bookshop.”

Cuneo says he has witnessed some [curious] things. He has, for example, seen a 250-pound accountant from Long Island put a diminutive pastor in an airplane spin worthy of Wrestlemania (and then not remember any of it later). He has seen a “mass deliverance” in Wheaton, Ill., where 600 people groveled in their Sunday best – moaning, groaning, spitting, vomiting into plastic buckets and simulating sex acts.

And he’s come to Monroe, Conn., to visit with Rev. Robert McKenna of Our Lady of the Rosary Chapel, one of the most prominent and respected persons in the field of exorcism. McKenna showed him a video of the demonic possession of “The Wolf Man,” a fellow unable to control his urge to get on all fours and howl like, well, a wolf.

“If people are absolutely convinced that they are demonized, then only an exorcism will suffice,” says Cuneo. “I did not go into this research with any preconceived notions, and I was prepared to report anything I saw. I did not see spinning heads, navel-licking tongues, levitating bodies, moving objects – and yet sometimes I would be the only person in the room who didn’t. The most common responses to me would be, ‘Satan didn’t want you to see, Michael, because you’re a writer’ or ‘Michael, you yourself must have become demonized.’ Sometimes they’d offer to give me an exorcism. Once, in Wisconsin, a couple of Episcopalian exorcists said they were prepared to go ahead with the procedure right away. They opened the trunk of their car and showed me handcuffs, ropes and chains. I said, ‘Thanks, I think I’ll take a rain check.’”

“The hardest exorcisms to get are through the Roman Catholic Church,” says Cuneo, raised Catholic in Toronto. “They constitute only a miniscule fraction of the number performed. The Catholic Church goes to great lengths to rule out all other explanations, like fraud, psychopathology, schizophrenia.”

Although exorcisms in the Roman Catholic Church are mandated to be performed by an especially appointed priest (and only with the permission of his bishop), Rev. Robert McKenna has never been one to wait for official church approval. In fact, he has openly defied the church on this issue, and many others, for years, and in 1974 was dismissed from the Dominican order. McKenna is deeply bothered by the modernizing of Catholic Church rituals that resulted from the Second Vatican Council in the mid-1960s. In 1973, he joined the Orthodox Roman Catholic Movement (ORCM), composed mainly of disaffected priests who wanted to restore Catholic traditions. Years ago, a traditionalist French prelate consecrated him as Bishop McKenna, a title he now uses. And for the past several decades, he has, according to Cuneo, “been a fixture within the underground traditionalist movement of American Catholicism.”

“Father McKenna is part of a larger movement of traditionalist priests who have broken with the Roman Catholic Church,” explains Cuneo. “They are like spiritual gunslingers. They believe that the Catholic Church is beyond repair. McKenna was once a parish priest, but he now believes that the papacy is an apostate office. He and others in the breakaway movement are completely schismatic. They get their own bishops to sanction their activities. They have dynasties and lineages of bishops that are absolutely independent of the official Church.”

“I am an exorcist by default,” says McKenna. “The average Catholic priest did not want to hear about these sorts of cases, so people began coming to me for help. I don’t want to pass judgment on the non-Catholic clergy, but I can tell you that most Catholic clergy today barely believe in the devil.

“Demonic possession is a veritable plague, and it seems to be getting worse as time goes on,” he adds.

McKenna is hardly alone in his beliefs here in Connecticut, according to Cuneo. Not only are McKenna and renowned demon chasers Ed and Lorraine Warren based here, but one of the nation’s most respected psychiatrists, M. Scott Peck of New Preston, author of the phenomenal best seller The Road Less Traveled, has been a driving force in lending exorcism what Cuneo calls “middle-class respectability” and in opening the door to viewing exorcism from a scientific perspective, perhaps even as a therapeutic tool. Peck’s book, People of the Lie (1983), made it clear that he had dealt with individuals in his private practice who he felt were possessed by evil. One chapter, “Possession and Exorcism,” even details two successful exorcisms in which he participated.

Cuneo credits Peck with giving exorcism a cultural legitimacy. “Here you have the best-known psychologist in the world admitting to having participated in exorcisms and calling them an essential form of therapy.”

Peck continued to explore exorcism after publication of his book. He conducted conferences on the subject of evil and, he told Cuneo, “tried to establish a network of exorcists and sympathetic psychiatrists.” The effort never panned out, and Peck expressed his frustration to Cuneo, saying that “while many Americans seem open to the possibility of diabolic possession, most of the country’s intellectual and religious elites . . . have seemed determined to keep the door shut.”

•

While remaining somewhat skeptical, Cuneo does not dismiss the usefulness of exorcism out of hand.

“It is cathartic, there’s some visceral relief and it can be therapeutic. It is a very complex subject,” Cuneo explains haltingly. “Do demons exist or not? Did I see conclusive evidence of demonic infestation? No. But I did see a lot of exorcisms that I thought were positively beneficial to the persons receiving them. They walk away, at least for the short term, feeling relieved.”

Not all worked out this way. Cuneo is still haunted by the exorcism performed on a man in Kansas City who, while writhing and delivering up his demons, was shouting about how he stalked women and children and thought that Satan was commanding him to have sex with them. The exorcism seemed to relieve him of his obsessions, and he was allowed to leave, with no guarantee that there would be any follow-up.

“I asked myself how confident I was about my responsibility as a citizen in this situation. I was in an ethical dilemma: Is this man a menace?” says Cuneo, who followed the man outside to the parking lot. “I asked him to have coffee with me. We talked for three hours and I felt better about his prospects.”

Even so, Cuneo still has reason to doubt.

“I was glad when he contacted me eight months later, to tell me that he was doing better,” says Cuneo.

Las Vegas Weekly

Feeling Possessed? You’re Evidently Not Alone

By Joe Schoenmann

[excerpted]

MICHAEL CUNEO, author of “American Exorcism,” calls 1985 to 1995 the “age of satanic conspiracy” in the United States.

Schools were dealing with so-called “suicide cults” among teenagers. Geraldo was featuring allegations of satanic ritual abuse on his TV show. In 1991, “20/20” broadcast a live exorcism. In 1996, a Las Vegas counselor co-wrote an academic paper after a seven-year study of teenage involvement in Satanism.

Then there was Tipper Gore, hell-bent and holy-rolling her way through a crusade to Prevent Ozzy Osbourne, Judas Priest and other rock ‘n’ rollers from infecting our youth with subliminal satanic messages heard if you played their records fast enough or slow enough or backward.

“There were reports of rampant satanic ritual abuse at daycare centers,” Cuneo says. “And people were crawling out of the woodwork claiming to have recovered long-suppressed memories of hideous ritual abuse at the hands of relatives.”

Cuneo says that it was also widely alleged that upwards of 40,000 young Americans were being abducted and murdered by Satanists every year. He adds that the FBI investigated these allegations “without uncovering a shred of forensic evidence in support of them.”

“It was outright cultural hysteria,” Cuneo says.

●

Nowadays Las Vegas in particular must be strewn with Satanists (and by association, demons), because the business of exorcism is flourishing.

The question isn’t whether or not Vegas is a haven for demons. The question is how do you find a good exorcist to get rid of them. The city is not lacking clergy who perform spiritual cleansings, exorcisms, deliverances – whatever you want to call it.

“I have dealt with people I believe were possessed,” says Rev. Mark Patton of El Camino Baptist Church. “And I believe Las Vegas certainly is a hub of evil.”

Pentecostal minister Louis Rios of Alpha & Omega Church, a Spanish-speaking church on East Lake Mead, says he witnesses a deliverance almost biweekly during his routine church services. “It doesn’t happen every day,” Rios notes. “The last one, about two weeks ago, was just a youngster, about 25, possessed with a demon of depression and hate. The demon was telling him to be destructive or kill himself.”

Cuneo, whose book “American Exorcism” is being re-released this month in paperback, isn’t surprised by stories of Vegas clergy performing a rite that he witnessed and researched for the better part of two years. He’s seen them all, in every manner and form, all across the country and can think of no reason why Vegas wouldn’t have its share.

“I doubt that very many people in the United States have had a better opportunity to see demons in action,” Cuneo says. “I’ve sat in on dozens of exorcisms. Some were quick and seemingly uneventful, over and done with in scarcely a whisper. Others were marathon sessions with people vomiting, flailing, thrashing – sometimes pummeling their groins and flinging themselves to the floor.”

“But at no point did I say to myself, I’m clearly in the presence of some kind of inexplicable, supernatural presence here,” Cuneo says. “Some of it was unnerving and scary – but I didn’t see what I thought was clear evidence of the demonic.”

Like the time everyone in the room saw the possessed woman levitating – everyone except Cuneo.

“This occurred a number of times, where everyone but myself was seeing something – bodies levitating, heads spinning,” Cuneo says.

Not that Cuneo precludes the possibility of demonic possession; he just hasn’t been privileged enough to see it. So what was it that he was seeing?

“Exorcism fits in wonderfully with contemporary American society, because we live in a therapeutic culture, where we’re looking for the quick fix, the nostrum to solve all of our problems,” says Cuneo, who previously authored the critically acclaimed “Catholics Against the Church” and “The Smoke of Satan.”

“And if we’re absolved of personal responsibility in the process, well, so much the better,” Cuneo continues. “People’s shortcomings aren’t their own fault. They’re afflicted by demons of lust or marital infidelity. Or demons of failure or envy or anger. Exorcism is perfectly in tune with the therapeutic temper of the prevailing society. And in the short term, you’ll likely feel better about yourself after receiving one. It’s such a cathartic, emotionally cleansing experience.”

Religion Watch

Interview with Author Michael W. Cuneo About Exorcisms

By Richard Cimino

Religion Watch recently interviewed Fordham University sociologist Michael W. Cuneo about his new book, “American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land Of Plenty” (Doubleday, $24.95). In researching the book, Cuneo observed exorcisms in Catholic and Protestant churches, as well as interviewing exorcists and those undergoing the ritual.

RW: In your book you write that the news and entertainment media have fanned the flames of fascination and shaped people’s views on exorcism. Why all the fascination, particularly among the media?

Cuneo: On one hand, the media treat exorcism as something ludicrous, an absurdity. Yet the media — and academics — also hope I’ll corroborate rumors they’ve heard about exorcism, that I’ll be able to tell them that I saw spinning heads. When I tell them I didn’t come across anything like that, they’re disappointed. Exorcism has become for them this last frontier of the supernatural and the mysterious that transcends scientific control.

RW: You trace most of the public fascination about exorcism back to the book and film, “The Exorcist.”

Cuneo: The hero-priest in the [William Peter] Blatty book and movie became part of our cultural legacy. While priests were largely viewed as laughing stocks in the popular culture during this time [early 1970s], this was the one area where the priest was the hero. It enhanced the role of the priest [when] it was being devalued.

RW: The Catholic ritual of exorcism receives most of the attention. But Protestant charismatics were involved in exorcism since the late 1960s, yet it has been pretty much ignored in the entertainment and media worlds.

Cuneo: That’s because Roman Catholicism is seen by many as a repository of intrigue and mystery. It’s not that one [form of exorcism] is more effective than the other. It’s that the priest is connected with this 2000 year tradition of liturgical richness.

RW: Yet “The Exorcist” and Catholic writer Malachi Martin’s book “Hostage to the Devil” created “customers” for charismatic and evangelical exorcism?

Cuneo: Right, but for evangelical exorcism, the Satanist scares of the 1980s, [when there were reports of Satanic ritual abuse], were very influential.

RW: In recent years there has been a huge increase in Catholic exorcisms around the world. But you find that the current crop of exorcists in the church have low status in the church and fall short of the expertise found in the movies. You also describe in your book “renegade priests” who perform unofficial exorcisms. Are they stealing the thunder from the official exorcists?

Cuneo: There is an effort by Rome to professionalize the exorcists . . . The official exorcists are in great demand, and not just from Catholics. It’s the difference between surgeons and chiropractors and other alternative forms of medicine. A lot of people see the renegade priests as quacks.

RW: You write in your book that understanding the phenomenon of exorcism is helpful in understanding American religion. Why is that?

Cuneo: Scholars of religion haven’t even begun to plum the enormous significance of the popular entertainment industry. Hollywood has had a tremendous impact on everyday religious behavior and belief. The only shocking thing is that more academics haven’t discovered this. How could it not have an impact when people are bombarded by these media-generated images? Exorcism as currently practiced is a synthesis of tradition, ritual, media-generated images and narratives and therapeutic elements from the broader culture . . . I’ve been in exorcisms where the model of the priest-exorcist is Damien Karras [the priest in the Exorcist] This is religious life imitating an art form.

RW: Turning to the deliverance groups among charismatics and Pentecostals, where do you see these kinds of ministries going? It seems that Catholic and Episcopal charismatics have become leaders in these ministries.

Cuneo: Catholics and Episcopal churches can have these ministries even if their congregations don’t approve of them. I’ve talked to pastors [from other traditions] who were thrown out of their congregations [for their exorcism or deliverance practices]. It’s more difficult to get Catholic priests thrown out because they are appointed by the bishop rather than by the congregation. It’s also that Episcopal and Catholics have a stronger tradition and vocabulary of symbol and ritual to address these issues . . . Among the Pentecostals, exorcism has been strongly revived in the Faith movement, which is associated with the health-and-wealth teachings and [televangelist] Benny Hinn.

RW: It was surprising to read of the burgeoning interest in exorcism and deliverance among evangelicals who are not charismatic.

Cuneo: I don’t think it’s really reaching the mainstream evangelical. There’s a concern that it is theologically irresponsible and morally corrupt. They would say it’s buying into the ethos of victimization. The evangelical vocabulary of sin and repentance conflicts with [new teachings on exorcism]. By the way, I was very impressed with the way evangelicals approached exorcism. It was approached with real pastoral sensitivity and insight. Most [attemptss of evangelical exorcism] had some psychological benefits.

RW: In your book, exorcism starts off as a very rare and dramatic ritual, and as it became more common, it seemed almost bland and routine, taking on a 12-stelp, self-help appearance. Where it used to be a last resort, now it’s almost a first choice for some psychological problems. Do you see the domesticated nature of exorcism growing in the future, with maybe even a secularized version emerging?

Cuneo: There will always be very flamboyant exorcisms. There will always be a yearning for the dramatics and fireworks. People want dramatic confirmation that they are engaged in a battle with actual diabolic forces. What’s happened is that certain deliverance ministries have followed the 12-step therapeutic model, but many people are unhappy about it becoming so domesticated. The therapeutic value [of exorcism] comes from it being rare and secret. When it becomes too common it becomes like cheap currency.

The Pitch (Kansas City)

Divine Intervention

By Annie Fischer

WED 4/28

WHEN DARRELL MEASE gunned down meth kingpin Lloyd Lawrence, Lawrence’s wife and the couple’s paraplegic grandson, it didn’t take a jury long to sentence him to death. But then Pope John Paul II visited St. Louis on the day Mease was scheduled to die and asked then-Governor Mel Carnahan to commute Mease’s sentence. Carnahan obliged, raising many questions about the interplay of religion and society. Michael Cuneo wrote about the case in Almost Midnight: An American Story of Murder and Redemption, which he discusses at 7:30 p.m. Wednesday at Rockhurst University’s Mabee Theater, located in Sedgwick Hall (1100 Rockhurst Road). To register, call 816-501-4828.

Daily Camera (Boulder, Colorado)

Feature Article

Exorcisms, though rare, on the increase

By Kevin Williams

[excerpted]

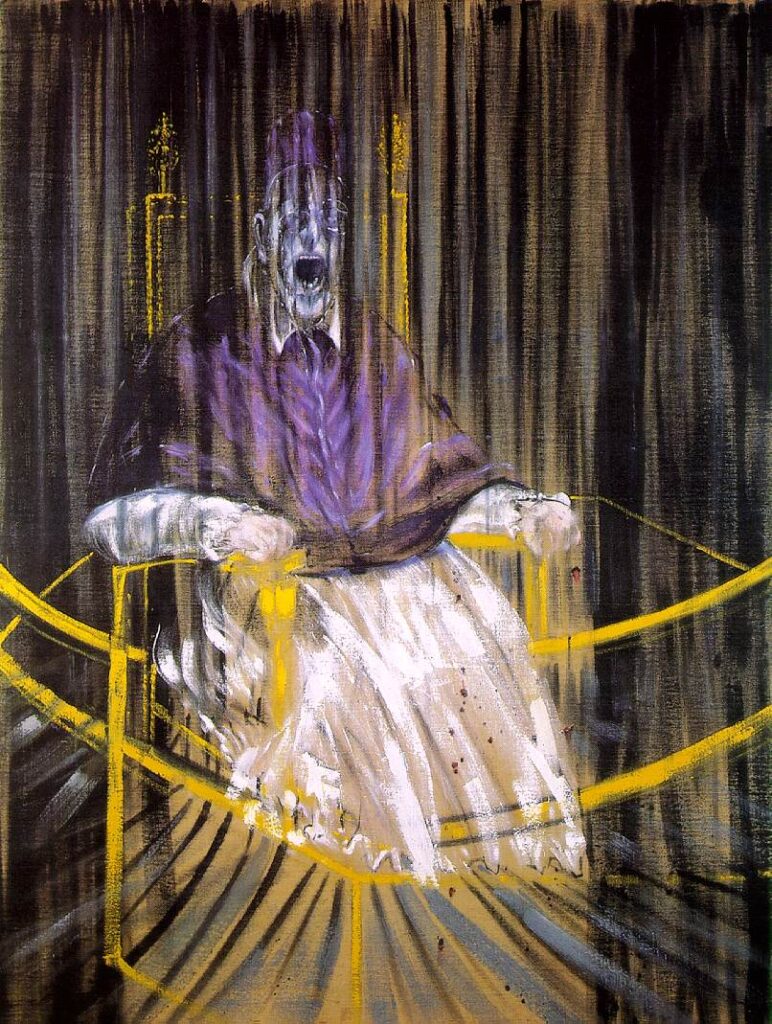

KNEELING DOWN, the priest makes his confession, renewing in his heart contrition for his sins. He then stands in front of the possessed, wearing a surplice and purple stole, and makes the Sign of the Cross and sprinkles Holy Water to invoke protection.

After the invocation, he pauses for a moment, summoning strength before reading from the traditional Catholic Rite of Exorcism: “Unclean Spirit! Whoever you are, and all your companions who possess this servant of God. By the mysteries of the Incarnation . . . tell me, with some sign, your name, the day and the hour of your damnation.”

Ever since “The Exorcist” first hit theaters in 1973, the American public has been fascinated with the subject of exorcism. And the religious community, which has historically been tight-lipped about the topic, has been somewhat more open in the past few years.

●

“There has definitely been an increase [in exorcisms] in recent years, and I think that there are two critical factors responsible,” says Michael W. Cuneo, author of “American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty.”

Cuneo cites the popular entertainment industry as the first reason for this resurgence.

“As recently as the late ‘60s, exorcism was all but dead and gone in the United States . . . it was a fading ghost long past its prime,” he says.

Then with William Peter Blatty’s novel “The Exorcist” coming out in 1971, followed by the movie, the entertainment industry found a new cash cow. More recent releases like “The Devil’s Advocate,” “The Blair Witch Project” and “Lost Souls” have kept interest alive.

“I would venture to say that if there hadn’t been these hugely successful movies, we wouldn’t have exorcisms today, or we’d have very few of them,” Cuneo says.

The second big factor, he says, is the therapy culture that is proliferating in America.

“All of these therapies are promising to cure people of their problems, restore their health, afford some kind of personal transformation,” Cuneo says. “Exorcism fits wonderfully with the therapeutic ethos of the broader culture.”

Although most people conjure up images of Roman Catholic rites when exorcism is mentioned, the truth is that “these constitute only a tiny fraction of the total number of exorcisms being performed in the United States today,” Cuneo says.

He points out that it’s still relatively difficult to get an officially sanctioned Roman Catholic exorcism. But there are plenty of other options available – “maverick” exorcisms in the Catholic tradition, evangelical Protestant, Episcopal charismatic, and Pentecostal.

Cuneo has attended more than 50 exorcisms and has seen “the possessed” regurgitate, thrash around, swear, self-mutilate and do any number of horrific things.

“[But] did I see unmistakable and conclusive evidence of demonization? No, at no point did I get that impression,” he says. “I didn’t encounter any real demonic grotesquerie – levitating bodies, spinning heads. Everything I saw was explainable, I think, in sociological, psychological, and medical terms.”

Even though he saw no indisputable proof of demons, Cuneo stops short from saying there’s no such thing as possession.

“Can demonization actually occur?” he asks. “Quite possibly, but I think it would be an exceedingly rare phenomenon.”

Although rare, Pope John Paul II himself performed an impromptu exorcism last year on a 19-year-old woman who went into a fit of rage in St. Peter’s Square, according to the Catholic News Service.

The pope’s actions, and the Vatican’s recent revision of the Rite of Exorcism, are implicit admissions that the Roman Catholic Church still takes the Devil and exorcism very seriously. The new rite, Cuneo says, dispenses with a lot of the archaic wording and places more emphasis on psychiatric evaluation.

If a parish priest believes that someone could be possessed, the case is turned over to diocesan officials, who go through an intensive interrogative procedure with the afflicted. If diocesan officials determine that an exorcism might be warranted, they bring in psychiatric professionals to discount the possibilities of mental disorder or fraud, a process than can take months or even years, Cuneo says.

After all of that, if diocesan officials still feel the person is possessed, an exorcism will be performed by a priest who is appointed by the local bishop.

What generally happens during an official Roman Catholic exorcism, according to Cuneo, is that the priest-exorcist will open with a prayer for all who are assembled. Often there are assistants and loved ones to help the procedure along. The priest will then query the possessed person about his or her problems before the Rite of Exorcism itself is read.

“It’s a very beautiful, moving and compelling rite,” Cuneo says, one that sent shivers up his spine the first time he witnessed it.

At certain points, the priest will make the Sign of the Cross, sprinkle Holy Water, and press a Crucifix against the possessed person’s temple. Cuneo says the reading of the rite takes a minimum of 30 minutes.

After it’s done, the priest and his assistants will take stock of the situation, and will often recommend follow-up therapy for the afflicted.

Whether it’s an official Roman Catholic exorcism or one of the other many variants, the person whom the rite is performed upon is obviously suffering some distress, Cuneo says. And while he admits there have been instances where people were hurt, or even killed, during exorcisms, he contends that overwhelmingly they are positive experiences performed by good people.

“Most of the exorcism ministers I’ve seen struck me as decent, humble and sincere,” Cuneo says. “And I think that [exorcisms] can be therapeutically beneficial, at least in the short term . . . as beneficial as most other therapies and decidedly more so than some of them.”

U.S. Catholic

Is the Pope Catholic?

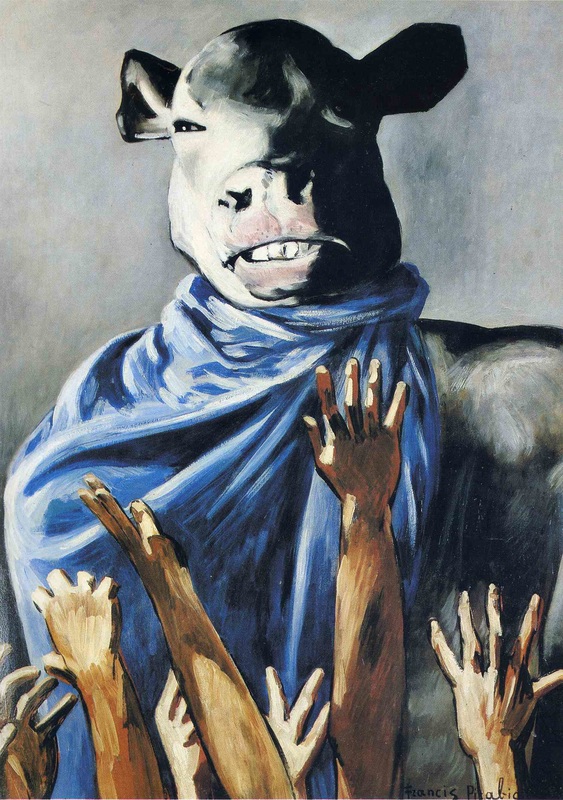

CANADIAN-BORN Fordham University anthropologist Michael Cuneo discovered that many militant prolife protesters in Toronto were Catholic conservatives who believed the church to be in crisis. It led him to wonder if such an animal existed in the United States. The result of his investigations is The Smoke of Satan: Conservative and Traditionalist Dissent in Contemporary American Catholicism (Oxford, hardcover; Johns Hopkins, paperback). The title refers to Pope Paul VI’s cryptic words in 1972, “Satan’s smoke has made its way into the temple of God through some crack.”

Travel with Cuneo, and you will meet conservatives ferociously loyal to the papacy, traditionalists who cling to a pre-Vatican II past, and apocalypticists whose antennae are tuned to messages from heavenly figures. While most Catholics would consider many – if not all – of the people Cuneo talked with to be marginal, they may be challenging the mainstream to question what it believes and what kind of commitments it makes. Cuneo is also the author of the forthcoming American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty (Doubleday).

THE EDITORS INTERVIEW MICHAEL CUNEO

How did you get interested in Catholic conservatives and traditionalists?

A few years ago, I wrote a book called Catholics Against the Church: Anti-Abortion Protest in Toronto (University of Toronto Press). In Canada, some of the most dedicated right-to-life activists – people going to jail for civil disobedience – were Catholics, but Catholics of a very particular theological disposition.

Almost all of them believed that Canadian Catholicism was in a state of crisis and had capitulated to the prevailing secular culture, and so it was up to them as a beleaguered minority to retrieve an ultimate Catholic commitment.

When I went to Fordham University in New York City, I was intrigued to investigate whether there were Catholic movements in the United States that bore some resemblance to the Canadian phenomenon. And, listen, I found more than I could’ve bargained for.

In America there is a near-bewildering variety of groups, movements, and publications – all of which hold that institutional Catholicism in the United States is in desperate condition. They’re convinced that something must be done to retrieve the authentic faith that has been lost.

What exactly do they feel has been lost?

First and foremost, a supernatural worldview. They believe that American Catholics, prior to the Second Vatican Council, shared a common sensibility. The signature of this was the sacred, incarnational universe that Catholics inhabited, which was exemplified by the sacramental life of their church.

A second – and related – concern is the question of cultural distinctiveness. Catholics in the 1950s believed that they were a people different in critical respects from mainline Protestants and from the broader society. Where, conservatives would ask, has Catholicism taken the worst beating in recent decades? In its liturgy. In sexual ethics. Prior to the council, nothing set Catholics apart from the prevailing secular culture more than the Mass and the church’s distinctive teaching on sexual ethics.

Prior to the council, Catholics knew implicitly what it meant to be Catholic. Now this has been lost. Now everything seems up for grabs and negotiable.

All the disparate groups I cover in The Smoke of Satan would agree that the Second Vatican Council was an event of extraordinary significance. The 1960s was a pivotal decade when, in their view, authority in general – and all structures and principles of authority – were being relentlessly challenged. That Vatican II took place at precisely this time, they would argue, is a big reason why Catholicism has gone into precipitous decline.

How real is the church they want to recover?

It seems to me that the Catholics I write about romanticize and sentimentalize the 1950s in some respects. That period seems to them far more uniform in terms of Catholic practice and belief – far more peaceful and pleasant – than it actually was.

What are the characteristics of the conservative position?

Conservatives, unlike some of the other groups I write about, accept the legitimacy of the Second Vatican Council. But they also believe that liberal theological elites in the American church and elsewhere have hijacked the council’s documents and given them an unwarrantedly subversive interpretation.

And conservatives without exception espouse a strict ultramontanism: They claim unbridled allegiance to the papacy of John Paul II. This is one of the hallmarks of Catholic conservatism in the United States. Conservatives locate ultimate authority in Rome. When all is said and done, Rome is the bastion, the center – our assurance of salvation.

What I’ve discovered, however, is that this is sometimes a highly selective ultramontanism. Certain papal teachings are easier to swallow than others, even for people who claim absolute and unqualified loyalty to Rome.

Another hallmark of Catholic conservatives in the United States is that they espouse total fidelity to Humanae vitae, Pope Paul VI’s 1968 encyclical prohibiting artificial birth control. They regard fidelity to Humanae vitae as the litmus test of authentic Catholicism. Are you, conservatives ask, with the prevailing consumerist, secular, sexually permissive culture – or are you with the age-old teaching tradition of the church?

What do they see as the distinction between the prevailing culture and Catholic tradition?

They believe that American society has gotten soft since the Second World War. It’s become an endlessly commiserating society. We have a proliferation of 12-step groups, the recovery movement, the codependency movement, the culture of victimization and complaint – the sense that we’re all somehow victims, and we’re all looking for recovery. And it’s so wondrously American because there are so many nostrums available for purchase and consumption, panaceas for whatever real or imaginary complaint or grievance we might be suffering.

What conservatives believe is that Catholic liberals have turned the church into just one more vehicle for addressing people’s personal grievances. If I’m feeling emotionally beleaguered, I can go to this particular ritual – something that happens to meet my needs at the time. But it’s my personal needs that are of paramount importance. Catholicism is now being reduced to just another kind of therapeutic outlet – nothing of profound importance. Nothing that you would live or die for.

Conservatives would say that most American Catholics have forgotten that the point of worship, finally, isn’t temporal well-being but rather eternal salvation.

What role do conservative prolife protesters play?

The most striking of the conservatives from my point of view are the antiabortion activists. In the United States, people generally assume that it was Operation Rescue, the evangelical Randall Terry’s outfit, that pioneered direct action and street militancy outside abortion clinics. But it was actually John Cavanaugh-O’Keefe and Joseph Scheidler, both of whom are Catholic conservatives.

For many Catholic conservatives, militant street protest against abortion is a kind of public ritual, a living testimony. It’s how they testify to their religious values and commitment.

The fetus – for conservatives – is a symbol of the transcendent. When they’re out on the street, they are not simply protesting abortion. They’re also making a dramatic statement about who they are as Catholics and what Catholicism should stand for at the start of the 21st century. This is why they engage in undisguised, blatant religious ritual and activity while they’re on the picket lines – brandishing images of Mary, praying the Rosary.

Strategically, this is disastrous. Where is it going to get you? One could argue that if you want to make a convincing case against abortion, you have to do so on secular grounds – appealing to science, civil rights, and so forth. You have to compartmentalize some of your religious convictions.

But when you go out there and pray the Rosary and sing hymns, you’re not engaging in instrumental protest. You’re engaging in symbolic protest. You’re making a statement about yourself and your religious convictions. And that’s the thing with conservative Catholic activists: They seem as much concerned with announcing their religious identity and their aspirations for salvation as with influencing the debate on abortion.

As an interesting sideline, almost all of these militant, conservative Catholic protesters espouse a philosophy of nonviolence. They’re opposed to the death penalty, for example. This is something you don’t get from the news media.

What do conservative Catholics have to offer the church in the United States?

A constant reminder that the current compromise between American culture and Catholicism is not the last word. Catholics must find ways to be more faithful – more truthful – to their traditions. And they also must be concerned with finding ways to engage more productively, fruitfully, and creatively with cultural developments. Conservative Catholics can also serve as a reminder that passive compliance isn’t necessarily an appropriate response to social change.

Do you sense that conservative young people have a much better knowledge of the Catholic faith than more liberal Catholic college students?

There are fairly new and alternative conservative Catholic colleges – Thomas More in New Hampshire and Christendom in Virginia, for example. I spent some time at these places, and I remember thinking, “Boy, I wish I could discuss Aristotle and Aquinas with my Fordham students the way I can with these kids.”

We have to recognize that some of the grievances held by conservatives are absolutely legitimate – especially rampant theological illiteracy within American Catholicism. Some of my Fordham undergraduates have never heard of basic Catholic doctrines that an earlier generation would’ve taken for granted.

When I visited these conservative Catholic colleges, I was impressed with certain things and less so with others. Students should be literate about developments outside of the tradition, too. They should be critically engaged with that. The sectarian response will likely always be inadequate as a Catholic response. My students at Fordham are more creatively engaged with certain intellectual and cultural developments outside of the Catholic tradition, but some are woefully illiterate about the Catholic tradition itself. At these conservative Catholic colleges, it’s typically the reverse.

How many conservatives are there?

Probably five percent, at most, of American Catholics. But there are a lot of American Catholics who’d be sympathetic. There are a lot of Catholics who’d think, “We like the ideals.”

Conservative Catholics insist not only that traditional teaching on sexual ethics and so forth be maintained, but also that everyone live up to it. A lot of other Catholics would say, “No, we can’t live up to it, but that doesn’t mean we want the teaching changed.” A lot of ordinary Catholics seem comfortable with that kind of split mentality.

How are conservative Catholics able to have an influence beyond their numbers?

Instant mobilization. Rapid response. If there’s a bishop they don’t like, they mobilize. They’ll organize letter-writing campaigns and boycotts, and do so very effectively. Catholics, historically, haven’t been very good at that in the United States. But these people have been influenced by the direct-mail campaigns of the Moral Majority and Protestant evangelicals in general.

They’ve incorporated those political and organizational tactics into their own apparatus. They give the impression of being much larger than they really are because they’re so heavily mobilized. They’re able to make appeals to Rome directly, and some conservative groups have sympathetic ears in the Vatican.

What about the second group you write about, the Catholic traditionalists or separatists?

Whereas conservatives locate ultimate authority in the papacy and accept – grudgingly, sometimes – the validity of the Second Vatican Council, separatists – I call them separatist although their preferred term is traditionalist – reject unequivocally both the Second Vatican Council and the new Mass.

They think that the council was a conspiratorial undertaking designed to subvert authentic Catholicism. They differ on how the conspiracy came about, but the council itself in their view was entirely illegitimate. They regard the new Mass as a counterfeit of authentic Catholic worship, an ugly caricature.

And so they place ultimate authority not with Rome but rather with the presumably “unchanging” and “unvarying” teachings of Catholic tradition – they love those words. The Council of Trent would be their historical center of gravity. And many traditionalists are convinced that Pope Pius XII was the last authentic pope, although some would keep open the possibility that John Paul II, for example, is an authentic pope.

But the really radical traditionalists, the sedevacantists – those who believe that the papal throne has been vacant since the death of Pius XII – absolutely repudiate not only the Second Vatican Council and the new Mass, but they also reject all the popes of the council from John XXIII on. They believe these are antipopes, imposters, precursors of the anti-Christ, or quite possibly even the anti-Christ.

Sedevacantists have cut themselves off completely from the institutional church. And if you follow their logic, this is something they have to do because in their eyes the institutional church is apostate.

Imagine that you’re a devout Catholic, and you’re convinced that Rome is making pronouncements that directly contradict centuries of Catholic teaching. You were always told that outside of the Catholic Church there was no salvation, and then the Second Vatican Council comes out with its documents on religious liberty and ecumenism.

Traditionalists say: Is the institutional church now claiming that its age-old teaching was wrong? But how could it have been wrong? Isn’t the church indefectible? It couldn’t have failed to be right. Which means that the church which is altering traditional doctrine is really a bogus church. So they believe that the only way to preserve authentic Catholicism – a Catholicism that is constant in its fidelity to unchanging, timeless, invariable Catholic tradition – is to break away from the institution. They see themselves as the true believers, the remnant church.

How do they organize themselves?

Traditionalists use the Tridentine Mass. They have their own church plants and complexes, but they also have their own priests, nuns, schools, and very often their own bishops and episcopal lines of succession. Their priests and bishops are not recognized by Rome, of course.

What traditionalists try to do is build theological utopias-in-miniature – countercultural communitarian structures that permit them to preserve authentic Catholicism. Many of the people living in separatist communities whom I interviewed had pulled up their roots – given up careers, moved their kids – and were economically improvising. Imagine the impressive level of commitment this reflects! All in the name of religious values and principles.

There’s considerable irony here. Catholic separatists are proliferating, and a big reason for this is that the United States is such a congenial place for the growth of culturally deviant and heterodox movements such as theirs. There is a long, rich history of countercultural religious movements developing and burgeoning on American soil, and it seems to me that Catholic traditionalists are tapping into this ethos.

They absolutely reject pluralism and view the United States as an irredeemably corrupt place, but they flourish on American soil precisely because of the pluralism that is entrenched here.

If these groups weren’t Catholic, would we refer to them as cults?

Yes, in the same way that we would have referred to primitive Christianity as a cult. Structurally and socially, primitive Christianity was strikingly similar to the groups we would castigate as cults today. Give up your previous life, turn your back on your previous commitments and lifestyle, and do something radically new because you now know the ultimate truth.

Would it be fair to characterize Catholic separatists as fundamentalists?