Contents

Trouw (Amsterdam) — Een Fellini-achtig religieus landschap

Archives de sciences sociales des religions (Paris) — The Smoke of Satan

Pro Mundi Vita (Brussels) — Le conservatisme catholique nord-américain

Cinenews (Antwerp) — Dossier Cinema

The Guardian (Manchester, UK) — American Exorcism

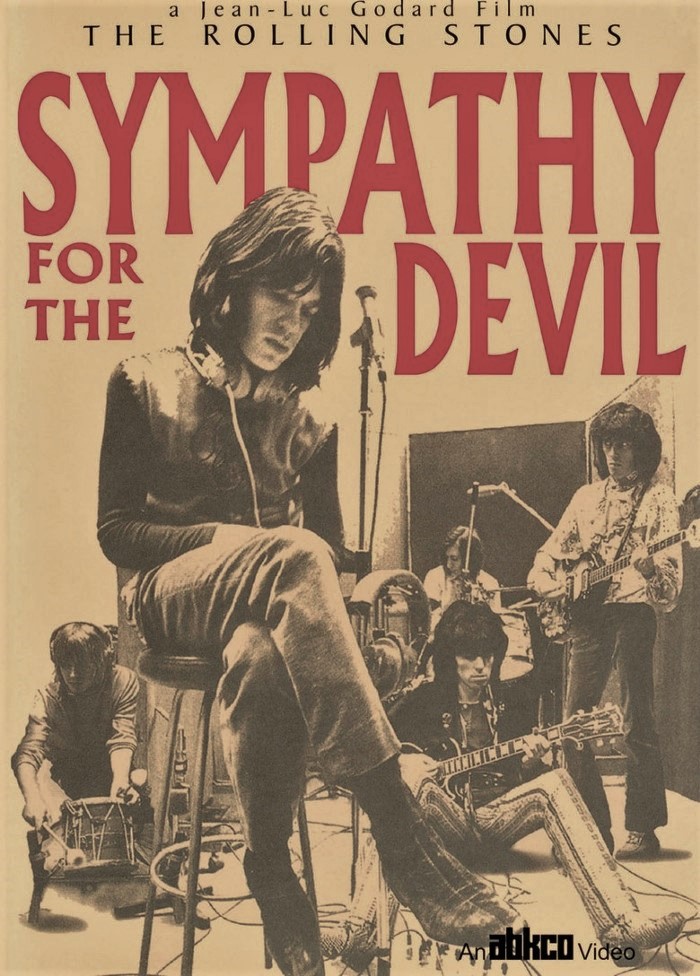

The Irish Times (Dublin) — No Sympathy for the Devil

Kristeligt Dagblad (Copenhagen) — Amerikansk eksorcisme

Montréal Gazette — Campagne de violence

Western Mail (Cardiff) — Dewis y Bagiau Papur

Irish Tatler (Dublin) — Hell Raisers

Ottawa Citizen — ‘Home Brew Exorcism’

The Herald (Glasgow) — American Exorcism

National Post (Toronto) — The Sun-Dance Secret

Birmingham Mail (UK) — Unholy War with Spirits in America

Sciences Religieuses (Ville de Québec) — Tempête en la demeure : Réflexions sur l’état des sciences des religions

The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, Australia) — Exorcism is making a comeback — and big news — worldwide

Medindia (Chennai, India) — Driving out the Devil

The Guardian (Manchester, UK) — Pope Francis and the psychology of exorcism and possession

Magonia Review (London) — American Exorcism

Penguin Random House Australia (Sydney) — American Exorcism

The Scotsman (Edinburgh) — The extreme religious sect which fuelled the passion of Mel Gibson

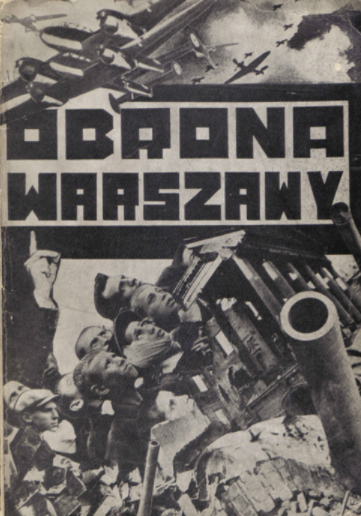

Saeculum Christianum (Warsaw) — Pismo historyczno-społeczne: American Exorcism

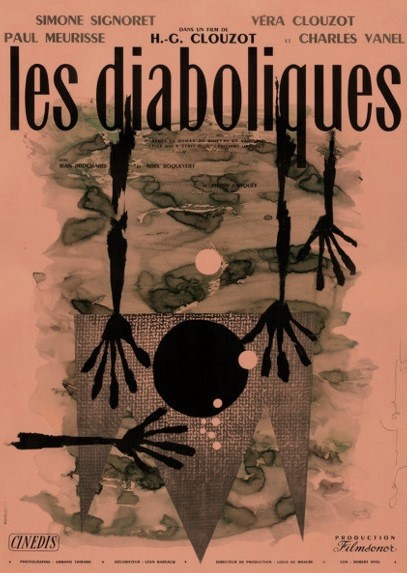

Little White Lies Magazine (London) — “The Exorcist” and the eternal struggle between religion and science

Saturday Night Magazine (Canada) — Birth Enforcement

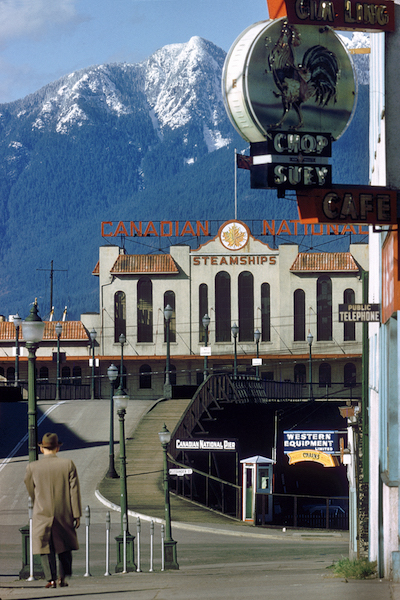

Trouw (Amsterdam)

Een Fellini-achtig religieus landschap

Michael W. Cuneo. The Smoke of Satan. New York (Oxford University Press)

door Richard Singelenberg

[excerpted]

HET ST PIUS V GENOOTSCHAP is een van de afvallige katholieke enclaves in de Verenigde Staten die de socioloog Michael Cuneo in zijn onlangs verschenen boek The Smoke of Satan in kaart heft gebracht. Want sinds Vaticanum II gist het ook in Amerika. Talloze katholieken, verontrust door de ingeslagen koers die uit dit kardinalenoverleg voortvloeide, habben zich verenigd in een Fellini-achtig religieus landschap van anti-abortus zeloten, radicale sekten, Maria-vereerders en Fatima-exegeten.

Zonder zwaarwichtige theoretische beschouwingen, maar met veel material uit eigen observaties, schetst Cuneo een boeiend beeld van deze, zoals hij noemt, ‘katholieke ondergrondse.’ Globaal onderscheidt hij een conservatieve richting, die zich met name profileert in de anti-abortusbeweging maar verder goede relaties onderhoudt met het Vaticaan, en een afvallig traditionalistische stroming die in het gunstigste geval de legitimiteit van de huidige paus in twijfel trekt.

•

Cuneo stuit op een wereld die bol staat van bloemrijke samenzwerings-theorieën, eindtijdprofetieën, rabiaat antisemitisme, onderlinge intriges en een fikse dosis paranoia jegens buitenstaanders in het algemeen en andersdenkende katholieken in het bijzonder. In die zin is deze katholieke onderbuik nauwelijks te onderscheiden van het bonte pallet van ultra-orthodoxe sekten van protestantse signatuur.

Dat geld took voor de meest radicale kenmerken. Geïnspireerd door Christian Identity, het groezelige mengsel van protestants fundamentalistisme en rechts-extremisme en een belang-rijk substraat voor de militia’s, sluiten ook sommige katholieke separatisten gewelddadig optreded in de nabije toekomst niet uit.

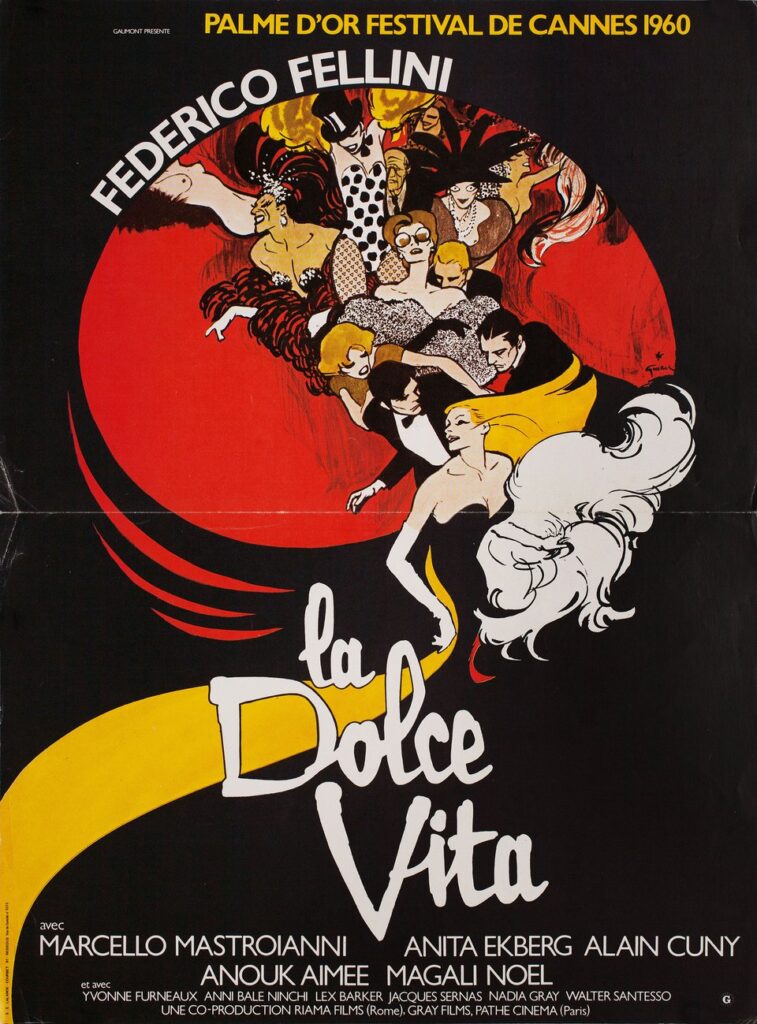

Archives de sciences sociales des religions (Paris)

Michael W. Cuneo. The Smoke of Satan. New York (Oxford University Press)

par Danièle Hervieu-Léger

EN SEPTEMBRE 1968, au moment où la publication d’Humanae Vitae suscite de vifs mouvements de protestation dans les courants libéraux du catholicisme américain, H. Lyman Stebbins, un agent de change à la retraite converti au catholicisme, fonde le CUF (Catholics United for the Faith), qui entend, dans ces turbulences, être la voix d’un catholicisme integral parfaitement fidèle au pape et résolument hostile à toutes les voix dissidentes qui suscitent le trouble et la division dans l’Église. Au moment même où le catholicisme américain accède à la pleine reconnaissance publique et abandonne la representation d’un ghetto catholique toujours menacé par l’Amérique protestante, il apparait traversé de conflits irrémédiables et menacé d’implosion. Depuis la fin des années soixante, la polarisation du catholicisme américain entre << libéraux >> et << conservateurs >> — polarisation renforcée par une tension qui traverse l’ensemble du champ religieux avec les conséquences politiques que l’on sait – s’est constamment renforcée.

L’intérêt du voyage que propose Michael Cuneo dans les différents groupes organisés du catholicisme ultra- conservateur est de faire apparaître que celui-ci n’est pas pour autant monolithique et qu’il rassemble des courants d’inspiration théologique et idéologique différents, unifies par l’intransigeantisme qui règle leurs relations avec la modernité sociale, politique et culturelle américaine. Des catholiques separatists rejetant en bloc les acquis du Concile Vatican II aux groupes activistes engages dans la lute contre la légalisation de l’avortement, en passant par les renouveaux d’une dévotion mariale intensive ou d’un apocalyptisme catholique activé par les défaillances de l’ultra-modernité américaine.

The Smoke of Satan identifie de façon vivante les différents modes d’invocation de la << tradition authentique >>. La description ethnographique des groupes et la reconstitution historique de leurs conditions d’émergence sont instructives.

Pro Mundi Vita (Brussels)

Le conservatisme catholique nord-américain

Cinenews (Antwerp)

Dossier Cinema

[excerpted]

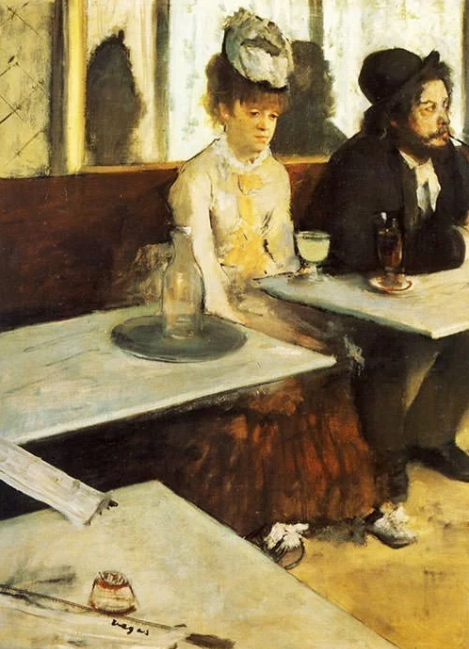

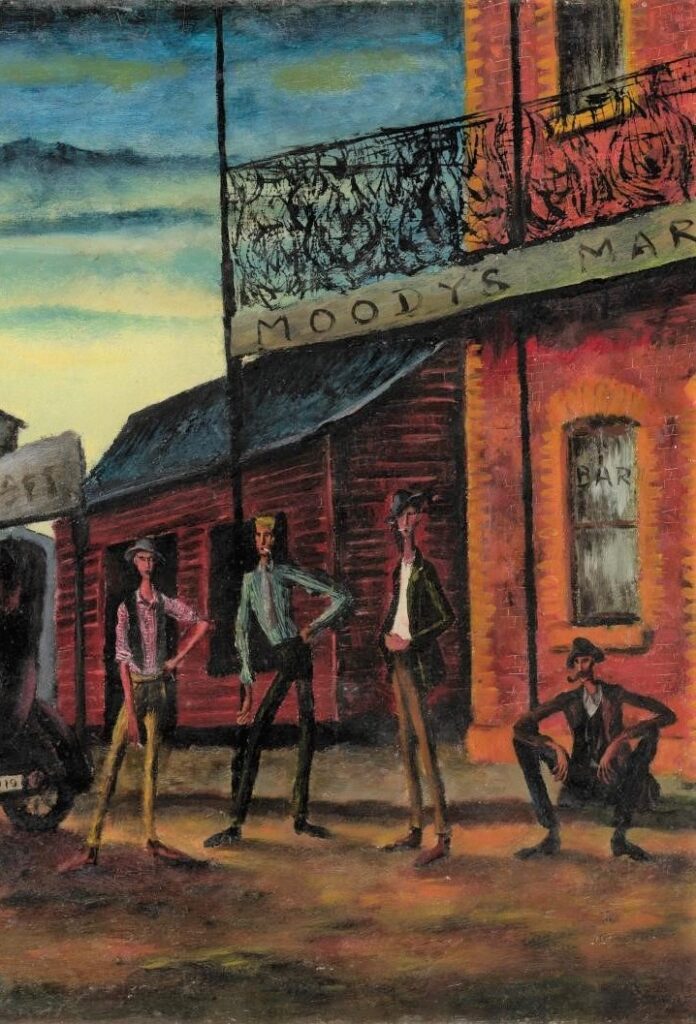

HET HUIVERINGWEKKENDE drama ‘Winter’s Bone’ heeft meer dan één reden om een bezoekje te verdienen en daar horen de vertolkingen zeker bij. De meeste aandacht gaat niet verwonderlijk naar de jonge hoofdactrice Jennifer Lawrence, die zich in de rol van de koppige Ree Dolly laat kennen als een enorme belofte. Zonder de steun van een paar rasacteurs had ze echter nooit zo kunnen schitteren, en een van die karakterspelers is John Hawkes. In ‘Winter’s Bone’ speelt hij Teardrop, de oom van het hoofdpersonage en een sujet waar je moeilijk hoogte van krijgt. Hij straalt intelligentie uit maar toch waag je je liever niet te dicht in zijn buurt, alsof hij onverwacht zijn giftanden kan laten zien. In levende lijve (op het filmfestival van Gent) is John Hawkes het exacte tegenovergestelde van zijn karakter, een zachtaardige, minzame en inschikkelijke man. Hij is al sinds jaren ’80 aan de slag maar loopt pas de laatste jaren wat in de kijker dankzij series als ‘Deadwood’ en films als ‘Miami Vice’ en ‘Me and You and Everyone We Know’.

Hawkes:

Er bestaat een boek, ‘Almost Midnight’ van Michael Cuneo, dat zich in die streek afspeelt en het over een moordzaak in het methamfetamine-milieu heeft. Ik heb dat boek gekoesterd als een Bijbel. Het legde de geschiedenis van de regio uit, waarom de mensen zich zo introvert gedragen. Waarom ze de overheid en de wet niet vertrouwen. Waarom ze liever afgeschermde gemeenschappen vormen waar ze doen wat ze willen zonder inmenging van buitenaf. Cuneo heeft het ook over bars die toeristen beter vermijden als ze in de streek zijn. Ik wil niet opscheppen maar dat waren de eerste plaatsen waar ik naartoe ben gegaan. Ik wou zien of ik me onzichtbaar kon maken en iedereen observeren. Meestal dachten de mensen dat ik een truckchauffeur of een seizoensarbeider was. Daar heb ik ook veel aan gehad.

The Guardian (Manchester, UK)

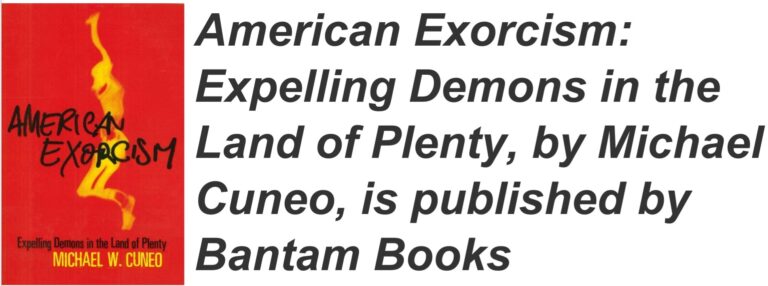

American Exorcism, by Michael W Cuneo (Bantam, £6.99)

By Steven Poole

IN THIS FASCINATING cauldron of investigative sociology, Cuneo travels around America witnessing exorcisms, trying to discover why demons seem to be in the ascendant. Much of the credit goes to The Exorcist, which, as Cuneo notes, concretised a notion of the priest-hero in popular culture. Cuneo also investigates “evangelical deliverance”, a lightweight, new-age flavour of exorcism, in which all personality defects can be ascribed to demonic influence and thus cured by a charismatic preacher. But the real action, as always, is in the Catholic church. Cuneo meets battle-scarred old priests with hair-raising stories, and psychiatrists who keep an open mind, but he never witnesses anything supernatural: the levitations and babblings in Latin always happen just after he’s left. Perhaps, as someone says to him, Satan just didn’t want to reveal himself to a writer. The devil’s greatest trick, after all, is convincing us that he doesn’t exist.

The Irish Times (Dublin)

No Sympathy for the Devil

By Anna Mundow

ON A MUGGY night in a packed auditorium outside Chicago, author Michael Cuneo recently watched white, middle-class Americans going berserk. “Throughout the auditorium, demoniacs are paired off with exorcism ministers, wailing, thrashing, regurgitating,” Cuneo wrote at the time. “Demons are being expelled in gushes of vomit and strands of mucus, and assistants pick their way through the heaving mess, handing out paper towels, holding paper bags up to peoples’ chins . . . across the hall, an attractive, middle-aged blonde woman named Linda wails constantly, a high-pitched air raid siren of a voice. Young children roam the hall, taking it all in nonchalantly.”

That night, Linda expelled her “Catholic demons”, thanks to evangelical Pastor Mike (“the hardest working exorcist in America”) who roared “Oh, yes, Roman Catholic demons, you’ve got to go . . . Mary, Queen of Harlots . . . Popes of the Antichrist . . . Demons of infant baptism . . . Demons of scapulars . . . ” And so on. Many other entities were similarly trounced – demons of depression, fornication, divorce – and at 11 p.m., people were ordered to “box” or “bind” their remaining demons until their next airing.

Which would be soon.

“Exorcism is a booming business in contemporary America,” explains Cuneo, the author of American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty. “And not just among charismatics . . . I have personally encountered more varieties of Catholic exorcism – official Catholic exorcism, bootleg Catholic exorcism, you-name-it Catholic exorcism – than I ever imagined existed.”

The Vatican has noticed. In its most public response to the proliferation of freelance exorcists – the 1998 publication De Exorcismis et Supplicationibus Quibusdam (Of Exorcisms and Certain Supplications) – it revised an exorcism rite that has been in use since 1614, this time emphasising the importance of prior medical and psychiatric examination while toning down the more colourful descriptions of Satan.

“The Vatican was very concerned about renegade exorcisms that capture the public imagination,” Father Christopher Coyne, a spokesman for the Boston Archdiocese, confirms. “The Church goes out of its way to avoid publicity and sensationalism. So, among other things, the Vatican called for every diocese to appoint an official exorcist, to put a tighter control on things.”

The number of full-time exorcists in the US Catholic Church was already rising. In the mid-1990s, there was just one officially appointed exorcist in the US. Between 1996 and 1997, however, that number rose to 10.

Ten official exorcists for 60 million Catholics in the US may not sound like a lot, but the Vatican’s initiative signalled a further increase. The archdiocese of Chicago has appointed a full-time exorcist for the first time in its 160-year history (he is currently investigating over a dozen cases), and New York City’s diocese now has four exorcists, including the Rev James LeBar, who became something of a legend in the field almost a decade ago when he assisted at the first televised exorcism in the US.

“Like it or not, there are many people in this country who are engaged in struggles with what they believe are demonic forces,” LeBar told Cuneo last year. “And because the Church, for quite some time now, hasn’t done its job in offering help to these people, many have been forced to turn to shady operators for help.”

Much of that help is offered by an astonishing variety of evangelical exorcist or deliverance ministries (600 by conservative estimates, but perhaps three times that many are currently operating in the US) whose healing services run from comforting to sinister.

Pastor Mike expelling Linda’s Catholic demons is an example of what Cuneo calls “the rough and ready school . . . a grapple on the floor, a slap on the back, a regurgitation, perhaps into a paper towel – no strings attached, take it or leave it”.

The Word of Faith Fellowship, by contrast, employs security guards and lawyers, promising health and wealth as it harangues the faithful into submission. “Miracle workers in pink Cadillacs and pinkie rings, soul-savers in three-piece glitter suits and $60 haircuts,” Cuneo writes. “This is the world of the Faith Movement. Gushing emotionalism, grasping materialism, tears on demand, hustles blessed with a thousand ‘Amens’.”

Evangelical congregations typically form around a charismatic minister or psychotherapist, and one of the most successful is the Rev Bob Larson, who runs an exorcism ministry in Denver, Colorado, and 40 exorcism teams across the country. “Our goal is that no one should ever be more than a day’s drive from a city where you can find an exorcist,” Larson recently told the New York Times. “Why should that freak us out?”

Catholic clerics may not be freaked out. But many are dismayed to see their flock straying to the evangelical outback and the rite of exorcism becoming a public spectacle. “Major exorcism is a very strict ritual applied in very rare cases after a thorough medical, psychological and spiritual investigation,” stresses Father Christopher Coyne. “If I’m the appointed exorcist, I’m the only person who has access to the ritual, and I carry it out in complete confidentiality.”

Explaining the difference between simple and major exorcism (the former is part of the baptismal sacrament), Father Coyne insists that baptism, confession and the eucharist continue to be the three healing sacraments in the Catholic Church.

But this is clearly too tame for a growing number of Americans who prefer their exorcism on demand, the more sensational the better.

Increased satanic activity is one explanation for that appetite. “The incidence of the demonic on the whole is rising,” Father Jeremy Davies, co-founder of the 200 strong International Association of Exorcists, observes from his Westminster diocese in the UK. “The existence of the devil isn’t an opinion, something to take or leave as you wish,” Cardinal Jorge Medina Estevez, a Vatican spokesman, agrees.

Others see cultural, not satanic, forces behind the current exorcism boom, of which perhaps the most potent expression was William Friedkin’s 1973 movie, The Exorcist. Based on Peter Blatty’s novel about a 1949 exorcism case in Washington, DC, this horror film continues to spawn hysterical fascination with demonic possession and the priest-hero.

“Making the movie was strange enough,” Father Tom Bermingham, an adviser on the film, told Cuneo. “But the aftermath was completely bizarre. Dozens of people contacted me every week . . . and they all believed that they or someone close to them might be demonically possessed.”

A few years later, Hostage to the Devil, a lurid account of five “real” exorcisms written by ex-Jesuit Malachi Martin, created more exorcism devotees, among them many alienated Catholic priests who condemned the reforms of the Second Vatican Council for giving Satan a free hand. “Before the Second Vatican Council, possession was extremely rare,” Father Robert McKenna told Michael Cuneo in 1996, “but after the council there has been a veritable plague of possessions . . . Vatican II and the new Mass gave an opening to the devil, and the devil has fully seized the opportunity.” (McKenna was dismissed from the Dominican order in 1974 for refusing to disassociate himself from the breakaway Orthodox Roman Catholic Movement.)

Back on terra firma, more subtle influences prevail. The self-expression movement of the 1960s, the charismatic and pentecostal awakenings of the that decade, the recovery movement in general, recovered memory therapy in particular and the satanic daycare abuse panics of the early 1990s all contribute to a hysterical, self-centred yet peculiarly self-exonerating approach to evil.

‘Part of the attraction of exorcism is the objectification of evil and the removal of one’s own responsibility,” says Father Coyne. “If evil comes into your life, it’s not because of anything you’ve done. It’s an outside agent. That’s very convenient.”

But Father Coyne points out that the Catholic tradition does not let the possessed off the hook: “Possession is usually assumed to be initiated by an invitation to evil on the part of the possessed. We ask what was going on in that life initially that might have precipitated the disorder. “

Having spent two years tracking exorcism ministries across the US and having observed 50 exorcisms, Cuneo admires clerics who quietly attempt to heal their parishioners, most often through prayer, sometimes through exorcism, frequently assisted by lay ministers.

Betty Brennan, for instance, born in Brooklyn, educated in a Loreto boarding school in Ireland, says that she is “the most experienced deliverance minister in American Catholicism”.

Working for the past three decades with Father Richard McAlear, she dismisses the “Hollywood theatrics and . . . the psychological acting out”, insisting that she and McAlear can “prohibit the demons from manifesting . . . We walk in and take the drama out of it”.

Calming voices such as Brennan’s, however, are currently drowned out by the howls of the possessed and the roars of their exorcist-showmen. For an increasing number of Americans, exorcism is drama – one that the Vatican can no longer direct.

Kristeligt Dagblad (Copenhagen)

Amerikansk eksorcisme

Af Merete Holck

BØGER UDEFRA: I USA er dæmonuddrivelse blevet den nyeste alternative terapiform. Det kan bruges til at forklare alt fra samlivsproblemer over depression til alkoholisme, og det har givet præster en helt ny efterspørgsel

Dæmonuddrivelse er den nyeste alternative terapi i USA, hævder den amerikanske sociolog Michael W. Cuneo. I nogle dele af middelklassen er dæmonbesættelser blevet en bekvem måde at forklare alt fra samlivsproblemer over depression til alkoholmisbrug på, og de »besatte« har hele tiden brug for flere uddrivelser. Derfor er der stor efterspørgsel på de præster, der har givet sig i kast med opgaven. »Personlig udvikling ved hjælp af dæmonuddrivelse: en smule griset måske, men forholdvis hurtigt og billigt, og moralsk retfærdiggørende. En gennemført amerikansk ordning,« skriver Cuneo.

Han har personligt overværet omkring 50 dæmon-uddrivelser hos både katolikker og protestanter. Han fortæller om sine oplevelser i bogen »American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty«. Cuneo underviser i sociologi og antropologi på Fordham University i New York.

Frem til 1970 var eksorcisme så godt som uddød i USA. Den nuværende bølge af dæmonuddrivelser startede i 1971 med udgivelsen af William Peter Blattys roman »Exorcisten« og med filmatiseringen af romanen i 1973. I 1976 udsendte den tidligere jesuit Malachi Martin den sensationsprægede bog »Hostage to the Devil«, i hvilken han hævdede at beskrive fem autentiske dæmonuddrivelser, han havde deltaget i. Blatty og Martin startede en bølge af bøger og film om dæmonuddrivelser. »Det er ikke meget af en overdrivelse at sige, at exorcisme i dag faktisk er opfundet af underholdningsindustrien,« skriver Cuneo. Og det har virket: I de forløbne årtier »har et overraskende antal hovedsageligt hvide, hovedsageligt middelklasse- amerikanere været overbevist om, at den moderne verden er stærkt befolket af dæmoner«.

De heroiske katolske præster i »Exorcisten« skabte meget opmærksomhed omkring katolske dæmonuddrivelser. Det førte til, at nogle katolske præster i det skjulte begyndte at udføre dæmonuddrivelser med det ældgamle eksorcismeritual, der stort set var gået i glemmebogen. Disse præster hørte især til på den yderste højrefløj.

En af dem siger til Cuneo, at det var det Andet Vatikankoncil, der gav Djævelen frie tøjler. Først i de senere år har den katolske kirke i USA offentligt taget initiativer på området: For et par år siden ansatte den katolske kirke i Chicago en fuldtidseksorcist for første gang i 160 år. I New York har fire katolske præster været beskæftiget med at efterforske ca. 40 tilfælde af dæmonbesættelse siden 1995.

Cuneo overværede dæ-monuddrivelser både i pinsebevægelsen, på den protestantiske højrefløj og i protestantiske mainstream kirker. Midt i 1980’erne begyndte en række protestantiske præster at uddrive dæmoner. Et af de steder, hvor der var mest røre om dæmonbesættelser, var pinsebevægelsen. Bevægelsen, der havde fokuseret på åndelige gaver som tungetale og profeti, blev efterhånden klar over, at ikke alle ånder var af det gode. Mange pinsefolk bad deres præster uddrive begær-, alkohol- og had-dæmoner. Desuden var mange protestanter bekymret over den påståede trussel fra satanisme i 1980’erne, og denne frygt gav yderligere næring til dæmonuddrivelserne.

Cuneo er ofte blevet spurgt, om han så noget overnaturligt i nogle af de mange dæmonuddrivelser, han overværede. Desværre nej, skriver han. Der var masser af opkast, men ingen hoveder, der drejede rundt, ingen kroppe, der svævede, ingen stemmer fra de døde. Alle de symptomer, de »besatte« klagede over, syntes at være fuldt forklarlige ud fra almindelig sund fornuft, skriver han.

Ikke desto mindre hævdede mange af dem, der undergik dæmonuddrivelser, at de havde fået det væsentlig bedre af det. Hvorfor? Fordi eksorcisme er »ritualiseret placebo«, skriver Cuneo. De »besatte« er på forhånd overbevist om, at deres problemer skyldes dæmoner. De forventer at få det bedre efter dæmonuddrivelsen. Og eksorcisterne selv og deres hjælpere forventer også, at dæmonuddrivelsen virker.

Det er nok til at give mange dæmonuddrivelser et positivt resultat, mener Cuneo. Men der er naturligvis også en bagside. Nogle mennesker bliver manipuleret til at undergå dæmonuddrivelser, og andre bruger dem til at vække opmærksomhed omkring sig selv eller til at undgå at tage ansvaret for deres fejltrin.

Cuneo konkluderer, at dæmonuddrivelserne passer bemærkelsesværdigt godt til den amerikanske terapi-kultur: »Med dens løfter om terapeutisk velvære og lynhurtig emotionel tilfredsstillelse er eksorcisme mærkeligt nok godt hjemme i indkøbscenter-kulturen i Amerika ved århundredeskiftet.«

Michael W. Cuneo: American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty, New York: Doubleday, 24.95 dollar.

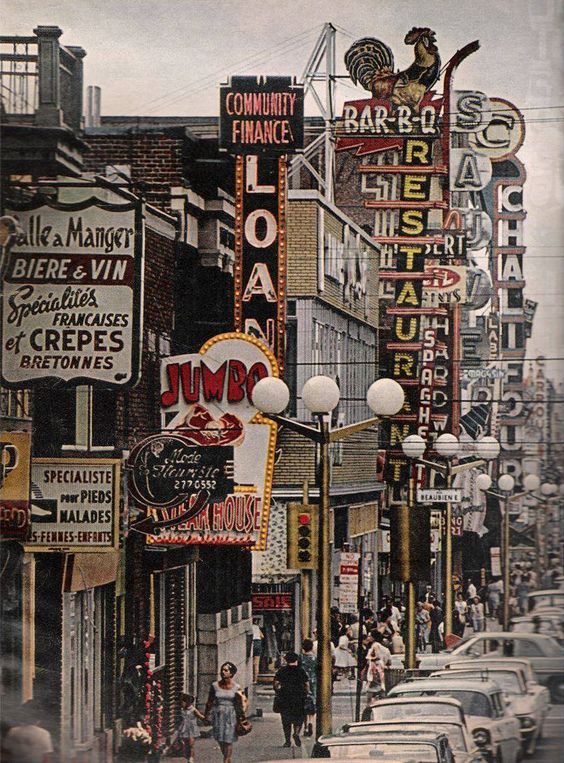

Montréal Gazette

Campagne de violence

par le personnel de la Gazette

[excerpted]

The anti-abortion movement is highly diverse, a loose coalition of organizations, informal groups and individuals. And like other social movements, it incorporates moderates and militants – those dedicated to pushing the cause through law, education and huge marches, and those who register their protests directly at the clinic doors.

“The division between the moderates and the purists in the movement is deep,” said Michael Cuneo, author of Catholics Against the Church, a study of Catholic anti-abortion activists. Among many of the most militant, he said, “it’s unqualified, no-holds-barred commitment.”

Western Mail (Cardiff)

Dewis y Bagiau Papur

American Exorcism/Michael W Cuneo/Bantam, £6.99

gan Dean Powell

EFALLAI NAD OES defod grefyddol arall yn fwy diddorol, neu’n fwy annifyr, nag exorcism. Mae hyn yn arbennig o wir yn America heddiw, lle mae gan y ddefod hynafol afael rhyfeddol o gryf ar y dychymyg poblogaidd.

P’un a yw’n cael ei gynnal gan exorcistiaid a benodwyd yn swyddogol, offeiriaid maverick neu garismatiaeth Esgobol, mae’n ymddangos bod exorcism yn fyw ac yn iach yn y mileniwm newydd hwn. Yn ddiweddar, penododd Archesgobaeth Chicago ei exorcist amser llawn cyntaf yn ei hanes 160 mlynedd, tra yn Efrog Newydd mae pedwar offeiriad wedi ymchwilio’n swyddogol i ddeugain achos o amheuaeth o feddiant demonig bob blwyddyn er 1995.

Mae Michael Cuneo yn myfyrio ar ystyr exorcism heddiw.

Irish Tatler (Dublin)

1 November is All Soul’s Day, time for good people to think about this life and the next. Do you believe in the world, the flesh and the devil? U.S. author Michael Cuneo says many people do, and that exorcists have never been busier . . .

By Vanessa Hariss

[excerpted]

“THERE IS PERHAPS no religious ritual more fascinating, or more disturbing, than exorcism.” These are the words of U.S. author Michael Cuneo, whose latest book is entitled American Exorcism. This isn’t the kind of knocking-on-walls, funny-smell-in-the-hall, isn’t-it-cold-in-here house exorcism either, but the full-blown casting out of demons.

In the States, exorcism (or ‘deliverance’) is thriving, so what’s caused this sudden interest? Films like The Exorcist started it off but, believes Cuneo, Americans are peculiarly predisposed to fall for demon-talk. “With its promises of therapeutic well-being and rapid-fire emotional gratification,’ he writes, “exorcism is oddly at home in the purchase-of-happiness culture” of the U.S.

So what happens here in Ireland? Perhaps unsurprisingly, it isn’t easy to find representatives of the different churches who are prepared to speak publicly about such a sensational subject. The Vatican isn’t so shy and in 1999 issued the first new exorcism ritual since 1614. The Pope even allegedly exorcised a woman in 1982, but all this feels very far away when phoning a diocesan office. The people I spoke to represented several faiths, and were all kind, measured men who were worried by superstition, but anxious to help troubled souls.

Cuneo emphasises that the U.S. Catholic Church is very unhappy about exorcism, saying that the only priests who will perform the ritual are renegade or ‘underground.’

The Church of Ireland does not have an official exorcist, nor do they have a specific ceremony. Instead, said my source, “It would be a laying on of hands with a simple prayer conducted within the context of the Church’s healing ministry; we would do the same thing for someone who was physically unwell.” After which, presumably, everyone has a nice cup of tea. This is a very different world from the Charismatic rituals picturesquely described by Cuneo as “puke and rebuke” sessions.

The problem that confronts everyone involved in exorcism is the spectre of mental instability. When do you know if someone is really possessed, or if they are suffering some serious form of disorder? ‘You just know,’ is the far from satisfactory answer.

The best we can hope for, perhaps, is the placebo effect. Cuneo makes it clear that many of the people he met claim to feel much better since being exorcised. The downside is that it attracts some damaged people who won’t be helped, and could be made worse by the ceremony. Cuneo refers to “self-glamorisation” and “cop-out” and people who “want to avoid responsibility for their own shortcomings by blaming them on demons.” He also reports that people have even been killed in the course of violent exorcisms.

Whatever you believe, it seems unlikely that belief in demonic possession will ever really get beyond the fringes of most faiths. Even Cuneo says, “I wasn’t counting on demonic fireworks, but neither was I counting them out. After all was said and done, more than 50 exorcisms – no fireworks, none at all.” So the jury is still out, but it seems that most people are backing medical science, despite the threat of Satan and all his works.

Ottawa Citizen

‘Home Brew Exorcism’

Man, 19, died bound to bed during three-day ordeal

By David Rider and Sarah Staples

[excerpted]

LONDON • DURING THE THREE days it took Walter Zepeda to die, neighbours heard many voices chanting and praying in his family’s home.

Now police are trying to determine how many people entered the apartment to see the 19-year-old strapped to a bed with neckties in what may have been an exorcism gone horribly wrong.

Michael Cuneo, author of American Exorcism, said yesterday all indications suggest Mr. Zepeda was the victim of a botched home exorcism.

The Toronto-born Mr. Cuneo, now based in New York City, said these “home brew exorcisms” are very common. “People become convinced someone they know or love is demonized, so they sometimes take matters into their own hands,” he said.

Mr. Cuneo, who has witnessed many exorcisms during the course of his research, said it is not uncommon for people to be restrained in some manner. “You want to prevent the so-called demons from causing damage to anyone present,” he said.

The Herald (Glasgow)

American Exorcism by Michael W Cuneo. Black Swan, £6.99

EXORCISM, says Michael Cuneo, is “a booming business.” Yet as recently as the 1960s it was an all but forgotten practice, and only became popular again after the huge success of William Friedkin’s 1973 film The Exorcist. Indeed, the entertainment business has spawned more demons than Old Nick himself – a scary number of Americans still believe their teenagers’ sullenness is caused by Satanic messages on heavy metal records. But Cuneo, a witness to more than 50 exorcisms, examines the phenomenon with objectivity.

National Post (Toronto)

The Sun-Dance Secret

By Patchen Barss

Did the Virgin Mary visit three shepherd children and tell them a trio of profound secrets? The Pope thinks so. But skeptics say there are other explanations for the supposed apparition in a Portuguese town in 1917

MONTREAL, Aug. 12 — CAN YOU KEEP A SECRET? The Pope sure can. When he visits Fatima, Portugal, today, with an expected audience of one million people in attendance, Pope John Paul II will be keeping quiet about a biggie: a holy secret that was reportedly revealed by the Blessed Virgin Mary to Lucia de Jesus dos Santos and her cousins, Jacinta and Francisco, at that same spot more than 80 years ago.

Despite tremendous pressure from many Catholic organizations, the Pope will not likely put an end to the speculation surrounding Lucia’s secret. Theories about the content of the mysterious message include warnings of apocalypse and apostasy (falling away from the faith), while theories about why it has not been revealed lean toward conspiracy.

This secret is particularly intriguing because the events surrounding it are not shrouded in mystery.

On May 13, 1917, the story goes, the three shepherd children were tending their flock in a field several kilometres west of Fatima. A flash of lightning frightened them, driving them toward an oak tree. Among the leaves of the tree, they espied a radiant figure, a woman, who spoke to Lucia. The figure said she would identify herself to the children six months hence, and in the meantime, they were to return to the site on the 13th of each month.

Word of the apparition got around, and every 13th, a bigger crowd gathered at the tree. By October 13, 70,000 people stood in the field waiting for a miracle. They got what they were looking for. Witnesses said the sun danced and bobbed in the sky (this came to be known as “the miracle of the sun”), and the radiant figure, by then identified as the Virgin, passed on a three-part revelation to Lucia about upcoming religious and political matters of the 20th century.

Lucia, who is now a 92-year-old cloistered nun, revealed two parts of the message in her memoirs. In the first part, the Virgin gave Lucia a quick glimpse of Hell, but promised that the three children would go to Heaven. The second part predicted the end of the First World War, but warned that a larger war would ensue, and that if Russia were not consecrated to her Immaculate Heart, the country would rise up to spread atheism and religious persecution across the world.

Sister Lucia never publicly revealed the third part of the secret, and today it is known only to her and to a few higher-ups in the Catholic Church.

The most popular theory about the third secret is that it speaks of a time of trial and tribulation for the Church, when many will fall away from the faith. The Vatican won’t reveal the secret, this theory goes, because it speaks of this apostasy occurring at the highest levels of the Church. Other popular theories include predictions of the apocalypse, the Antichrist or the second coming of Christ – or all of these.

Michael Cuneo, whose book The Smoke of Satan (Oxford University Press) examines conservative dissent in contemporary Catholicism, said in an interview that ideological extremists are the people most passionately concerned about the content of Lucia’s secret.

“There’s a whole industry within the right-wing of international Catholicism that traffics in this kind of thing,” he said. “An underground industry that really flourishes. There’s definitely a market for conspiracy theory involving the Vatican.”

But most pilgrims to Fatima, Cuneo went on, are hardly obsessed with the secret.

“They derive comfort from the idea that miracles might still be possible in the modern age,” he said. “They derive fellowship and pious entertainment from the festivities at the shrine. The secret? It’s not something that’s uppermost in the minds of most Fatima devotees.”

Cuneo is a Catholic and a Canadian who is a professor of anthropology at Fordham University in New York. He said he can’t claim to know the truth about such apparitions. “I approach this stuff from an attitude of what I’d describe as open-minded Canadian skepticism,” he said.

Joe Nickell, a senior research fellow at the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, is more skeptical than Cuneo. In his book Looking for a Miracle (Prometheus), he argues that the events at Fatima can all be explained in scientific, non-miraculous terms.

He thinks Lucia suffers from what psychologists call “fantasy-proneness.” Fantasy-prone people are neither insane nor dishonest, but they are predisposed to, among other things, having imaginary friends when they are young (long before the Virgin Mary spoke to her, Lucia had imaginary playmate angels) and to believing that they have been approached by supernatural beings (angels, aliens, ghosts, etc.) who give them a special message to pass on to humanity.

Nickell said that debunking Fatima or questioning the significance of the third secret does not represent an attack on Catholicism. “We at CSICOP don’t investigate religion, but we do investigate claims that are made in the name of religion that are investigatable.”

Michael Cuneo is comfortable with that. “When the institutional Catholic Church approves an apparition, what they are saying is, ‘Well, it seems that there is nothing here contrary to Catholic faith,’” he said. “Approval does not carry any kind of mandatory note or obligation to believe. In other words, you can still be a good Catholic and say, ‘I think this is a crock.’”

Birmingham Mail (UK)

UNHOLY WAR WITH SPIRITS IN AMERICA

AMERICAN EXORCISM by Michael W Cuneo (Bantam Books, £6.99)

By GY

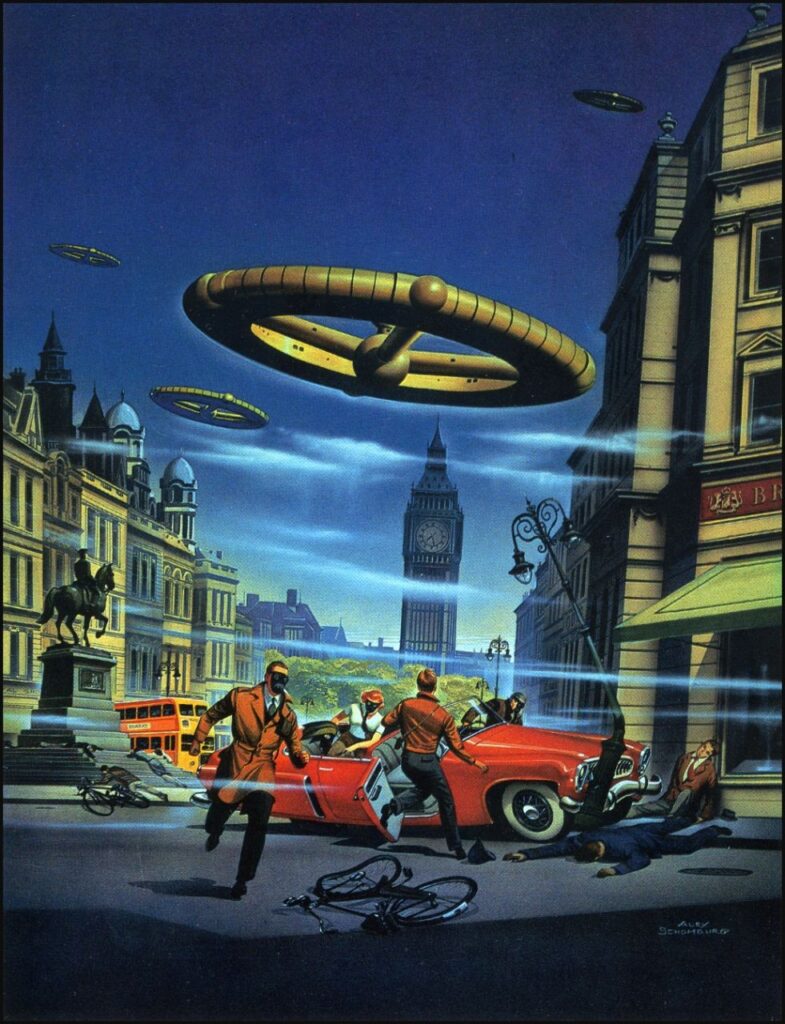

AMERICAN EXORCISM tells the strange-but-true story of one of the USA’s real boom industries of modern times – dealing with demons.

In his entertaining and down-to-earth study Cuneo starts with the controversy sparked by the 1973 horror movie The Exorcist and tells how official Catholic exorcists, maverick priests and charismatic evangelists have tackled people who believe they are possessed by evil.

With objectivity, irony and a large pinch of salt he effectively describes a phenomenon which is preposterous to some but terrifying and all too believable to others.

Sciences Religieuses (Ville de Québec)

Tempête en la demeure : Réflexions sur l’état des sciences des religions

par Mathieu Boisvert

[extrait]

L’article << Of Demons and Hollywood : Exorcism in American Culture >>, de Michael W. Cuneo, s’engage dans une entreprise différente. L’auteur essaie ici de démontrer les liens étroits entre la résurgence du phénomène de l’exorcisme aux États-Unis et les médias. Jusqu’à un certain point, on pourrait affirmer que cet articles suit les pistes de Noam Chomsky, car Cuneo arrive à la conclusion qu’il y a un lien inéluctable entre l’émergence et le maintien de certaines orientations et/ou pratiques religieuses et les émissions populaires diffusées sur nos canaux de télévision.

The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, Australia)

Exorcism is making a comeback — and big news — worldwide

By Jamie Seidel

[excerpted]

But is exorcism actually on the rise?

Michael Cuneo, sociologist and author of newly published “American Exorcism,” asserts “Exorcism is more readily available today in the United States than perhaps ever before.”

He goes on to say: “By conservative estimates, there are at least five or six hundred evangelical exorcism ministries in operation (in the US) today, and quite possibly two or three times this many.”

Australia? It’s not telling.

Unlike their overseas counterparts, Australian Catholic diocese have been backwards about coming forward with the exploits of their proactive priests.

But they’re certainly there.

Medindia (Chennai, India)

Driving out the Devil

By Thilaka Ravi

[excerpted]

Recording real-life exorcism in his book American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty, Michael Cuneo, professor at Fordham University in New York City, mentions an official church-sanctioned exorcism he watched. It involved a man (the possessed) who was a heavy drinker, had sex with whomever, whenever, was generally depressed, and had recently begun to hear voices, see things, and feel an “unbearable pressure” on his body at night. With the sanction of a psychiatrist an exorcism was arranged. Without much of the drama seen in movies, the priest prayed over the man in the basement of a building, sprinkled holy water, made the sign of the cross, and exhorted the devil to leave the man in peace. Mr. Cuneo writes, “Warren said he felt peaceful, but was also a bit confused. He thought he felt something leaving him during the exorcism, but he wasn’t sure.” There may be those who believe in exorcism and those who don’t. But Cuneo wonders: If the patient feels better after the exorcism and no one was hurt in the process, why object to it?

The Guardian (Manchester, UK)

Pope Francis and the psychology of exorcism and possession

By Chris French

[excerpted]

Last week it was reported that Pope Francis had formally recognised the International Association of Exorcists, a group of 250 priests spread across 30 countries who supposedly cast out demons.

Belief in possession is widespread both geographically and historically and is far from rare in modern western societies.

Although it may not always be immediately obvious, there are often benefits to enacting the role of being possessed. Indeed, in many societies, certain forms of possession are welcomed. For example, glossolalia, or “speaking in tongues”, is encouraged in many western Christian societies and is interpreted as possession by the Holy Spirit.

For less positive forms of possession, the benefits of taking on this role may be harder to identify but they still exist. As Michael Cuneo describes in his excellent book, American Exorcism, the phenomena of alleged possession and exorcism are much more widespread in the US than is officially recognised. For many people, the idea that all of their previous socially and morally unacceptable behaviour was not in fact their fault but due to possession by demons is appealing. Furthermore, once those demons have been exorcised, the repentant sinner is now welcomed back into the loving arms of his or her community.

Magonia Review (London)

Michael W. Cuneo ● American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty {Bantam Books, £6.99}

By Peter Rogerson

An account of Michael Cuneo’s encounters as an ‘investigative sociologist’ and observer among both Protestant and Catholic exorcists in the USA. Cuneo argues that the exorcism industry has grown into the mainstream of American culture, from a nearly forgotten backwater, following the publicity surrounding the film The Exorcist. The film and subsequent best-selling books such as Malachi Martin’s semi-pornographic Hostage to the Devil constructed images of what possession means and how it can be dealt with. Exorcism ministries grew up in a variety of charismatic, evangelical and theologically conservative groups across the United States.

In his searches Cuneo never actually comes across the sort of dramatic events he hears about, such as levitations and heads turning 180 degrees, though there is one occasion where everyone else present swears such a levitation takes place, but Cuneo sees nothing. One of the more rational Catholic exorcists having ‘seen’ such a levitation himself, now thinks that in some regard his senses were enchanted, and not by demons.

Those coming for exorcism suffer usually from a variety of anxieties; some would no doubt be diagnosed as suffering from obsessive compulsive disorder and others from depression of various severities. Others just seem to have normal human problems. Indeed, the main problem is their quite natural inability to achieve the impossible perfectionist demands of their sub-culture. In this, though it looks traditional, modern-day exorcism is very much an integral part of the contemporary therapeutic culture with its presentation of everyone as a victim (it’s not me, guv, it’s the demons), and its own perfectionism. The exorcists summon up dozens of demons to account for every human situation; the psychiatrists have ranges of diagnoses for an equal number of ordinary human situations. Behind both lies a perfectionism in which happiness is not just guaranteed by the Declaration of Independence but is mandatory, and if you are not permanently happy and satisfied you have a problem which needs professional help to solve.

If there is a lacuna in this book, it is perhaps a lack of attention to the deeper causes of the exorcism movement. The Exorcist was surely a child of its times; it is no coincidence that its ‘victim’ is a teenage girl who violates the community’s sense of appropriate behaviour; she is sexually aggressive, foul-mouthed and dirty, all phenomena of the 1960s youth rebellion. The Exorcist portrays the priest-hero (Cuneo’s phrase) as defending traditional religious and social values against disturbing forces, of reinforcing the boundaries of culture against the wild things outside.

Cuneo shows how the image of the priest-hero was attractive to many priests who found their traditional patriarchal role threatened by theological and social liberalism. In the Protestant exorcism groups, there is the equal suspicion that what is really being exorcised is secular modernity itself.

More could have been made of the very high profile of women in many of these groups, as both victims and ‘discerners of spirits.’ Women also have high profiles in possession cults in other cultures. As victims they can give vent to frustrations and aggressive tendencies repressed by the culture, and blame the demons. As sniffers out of spirits (yes, many discerners claim to detect the possessed by their body odour) they can gain power and status in cultures where they are usually expected to be submissive to male authority.

As a good sociologist Cuneo won’t pronounce as to whether ‘real’ demons exist, though readers can form their own opinions. As to exorcism he is ambivalent; as a placebo it may often be of real therapeutic value, but its culture of passing the buck onto the demons and the quick-fix solution make him uneasy.

Magonia readers will find many of Cuneo’s insights into the role of popular culture in the promotion of ‘deep’ beliefs and experiences, and in world view and perception-building, applicable across a range of topics.

Penguin Random House Australia (Sydney)

Eye-opening, disturbing, surreal and often funny guided tour through the burgeoning yet mysterious business of exorcism and the darker side of American life…

Conducted by officially appointed exorcists or by maverick priests sidestepping Christian sanctions, by evangelical ministers and Episcopal charismatics, the ancient rite of exorcism is flourishing in the new millennium. In New York alone, four priests have, since 1995, officially investigated over 40 cases of suspected demonic possession, the Archdiocese of Chicago has appointed its first full-time exorcist in over 160 years while exorcists have appeared on television, courtesy of the likes of Oprah Winfrey and Larry King. Written with objectivity, insight and a healthy amount of irony, AMERICAN EXORCISM is an inside look at this – to some extraordinary, to others preposterous and to many, terrifying – phenomenon. Having attended over 50 exorcisms in person, and interviewed many of the participants – both the exorcists and those who believed themselves to be possessed – Michael Cuneo explores this netherworld of American, and ergo Australian, life, and reflects on the meaning of exorcism in the 21st century, and on the relationship between religious ritual and popular culture. As well as recounting in gripping detail the ceremonies he witnessed, he touches on such provocative topics as the ‘satanic panics’ of the 1980s, repressed memory and ritual abuse. The result is a remarkably revealing, entertaining and fascinating work of cultural commentary.

The Scotsman (Edinburgh)

The extreme religious sect which fuelled the passion of Mel Gibson

By The Newsroom

[excerpted]

RELIGION has always made for good box office returns, from Ben Hur to Field of Dreams.

However, public interest in The Passion stems less from its “sand and sandals” epic qualities than from the religious controversy it has stirred up. The Passion unashamedly ignores the advice to film makers given by the legendary Hollywood producer, Samuel Goldwyn: if you want to send a message, use Western Union. In other words, don’t mix propaganda with entertainment. But that is precisely what Mel Gibson does in The Passion.

For Gibson is a passionate member of the Catholic Traditionalist movement, a minority (but growing) Catholic sect that rejects the reforms of the Second Vatican Council in 1964-65 – in particular the abolition of the Latin Mass. The Passion is nothing short of a party political broadcast for this movement, if only in the crude way Gibson’s earlier Braveheart was propaganda for the SNP.

The Catholic Traditionalist movement is not a monolithic body, organisationally or doctrinally. Nor is it that big: of America’s 63 million Catholics, estimates of the number of Traditionalists vary between a low of 50,000 and a high of 100,000. They worship in some 600 chapels across the States, many of which are independent congregations. Traditionalists also refrain from eating meat on Fridays and women wear hats in church. Leaving aside the X-Files lunatic fringe, most Traditionalists are just ultra-orthodox Catholics. They vary between those who see the Vatican reforms as the work of foolish liberals who will eventually see the error of their ways, and a more conservative wing which sees the Vatican as genuine heretics.

Is there anything to be feared from the Catholic Traditionalists, who are normally ultra-right-wing in their politics? Yes, says Professor Michael Cuneo, who studied their activities in his 1997 book, The Smoke of Satan. He thinks the Traditionalists “would like nothing more than to be transported back to Louis XIV’s France or Franco’s Spain, where Catholicism enjoyed an unrivalled presidency over cultural life and other religions existed entirely at its beneficence”.

Saeculum Christianum (Warsaw)

American Exorcism : Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty : Doubleday, Michael W. Cuneo, New York-London-Toronto-Sydney-Auckland

Bp Andrzej F. Dziuba

Wielka problematyka wszechstronnej posługi chrześcijaństwa obejmuje wszystkie dziedziny życia oraz wszystkie sytuacje życia indywidualnego czy społecznego oraz wspólnotowego. Otwarta jest na wielość tak radości jak i smutków. Ewangeliczne orędzie adresowane jest bowiem zawsze, w każdym miejscu i czasie, i to do wszystkich. Nie ma ono ograniczeń czy preferowanych dziedzin, sfer czy środowisk.

W bogactwo codziennego życia, rozeznawanego przez chrześcijan – tak to m.in. wskazuje objawienie – wpisana jest świadomość istnienia oraz działania złego ducha. Jest on przede wszystkim uświadamiany w kategoriach wiary. Współcześnie jednak jest on także jeszcze wyraźniej widziany oraz doświadczany w kategoriach zewnętrznych, wręcz fizycznych przejawów oraz działań. Wobec tych wielorakich przejawów czy form jego manifestowania się staje fenomen egzorcyzmów oraz osób je spełniających czy poddających się im. W przeszłości był on raczej związany tylko z Kościołem katolickim, co zresztą było jednym z tematów jego krytyki, ale dziś obejmuje szersze wspólnoty chrześcijańskie, a nawet i pozachrześcijańskie.

Bardzo popularnej i obecnej w wielu mediach problematyce egzorcyzmów w USA poświęcona jest najnowsza praca Michael W. Cuneo. Jest on wykładowcą socjologii i antropologii w Fordham University w Nowym Jorku a także autorem m.in. The Smoks of Satan oraz pisze artykuły m.in. dla New York Times i Los Angeles Times.

Prezentowaną książkę otwiera dedykacja (s. V) oraz klarowny spis treści (s. VII- -VIII). Nie mniej użyte tutaj sformułowania są raczej tylko hasłami a mniej autentycznymi wskazaniami odnośnie do prezentowanej treści.

Po podziękowaniach (s. IX) zamieszczono formalne wprowadzenie (s. XI-XV). Tu zaprezentowano m.in. materiały źródłowe, podano ogólny plany badawcze oraz omówiono układ całej książki.

Z kolei całość studium M. W. Cuneo podzielona została na sześć różnych objętościowo części, a w ich ramach kolejno wskazanych 16 rozdziałów czy bloków tematycznych. Te ostatnie niekiedy podzielono na jeszcze mniejsze fragmenty opatrzone specjalnymi tytułami czy innymi wyróżnieniami, choćby tylko graficznymi lub odstępami edytorskimi (s. 4, 7, 13, 14).

Część pierwsza, wprowadzająca nosi tytuł Egzorcysta jako bohater (s. 1-24). Autor nawiązuje najpierw do faktoru wywołanego przez książkę W. P. Blatty i powstały na jej podstawie film Egzorcysta. Mówi tutaj także o swoistych zakładnikach Malachiasza, widzianych szczególnie w kontekście egzorcyzmów.

Przedsiębiorcom czy impresariom egzorcyzmów poświęcona jest druga części prezentowanej książki (s. 25-70). To dotknięcie kwestii złego ducha jako kłamcy. Następnie jakby demoniczne zapaści czy upadki. Także ukazano tutaj kapłanów egzorcystów jako swoistych bohaterów, ale w takim rozeznaniu wymagających jakby pewnej rewizji czy nowego lub innego spojrzenia.

Część trzecia podejmuje zagadnienie charyzmatycznych świadectw ministrów praktykujących działania egzorcystyczne (s. 71-164). To nawiązywanie do idei wyzwolenia, ale jakże różnie pojętego oraz rozumianego. W to wpisują się szczególnie współczesne liczne w USA Kościoły i ruchu pentestekonalne. Nawiązuje się tutaj m.in. do swoistego szczytu charyzmatycznych wyzwoleń. Jakby z innej strony wskazuje się jednocześnie także na krytyczne czy dobre demony. Wreszcie autor, wpisują się jakby w psychologiczne tendencje, wskazuje także na terapeutyczne znaczenie egzorcyzmów.

Kolejna część ukazuje swoistą, czasem wręcz krańcowo przeciwstawną szkołę spojrzenia na prezentowane zagadnienie egzorcyzmów (s. 165-192).

Część piątka koncentruje się na pewnych osiągnięciach nurtu ewangelicznie pojętego wyzwolenia (s. 193-236). To dostrzeżenie swoistej konspiracji szatańskiej we współczesnym świecie. Z innej zaś strony to stanięcie wobec pewnego frontu licznych problemów czy początku dostrzeganej rzeczywistości.

Egzorcyzmy rzymsko-katolickie to tytuł szóstej części prezentowanej rozprawy M. W Cuneo (s. 237-269). To przybliżenie wiele oficjalnych i nie oficjalnych czy nawet quasi oficjalnych kwestii.

W całości zamieszczono ważne elementy formalne tj. zakończenie (s. 270-281), przypisy (s. 283-301) oraz indeks (s. 303-314).

Śledząc całość rozprawy M. W. Cuneo można zatem powiedzieć, że części pierwsza i druga pokazują popularność oraz znaczenie wręcz kulturowe bardzo zróżnicowanego przemysłu rozrywkowego w USA. Z innej strony ta właśnie sfera wyjątkowo stymuluje egzorcyzmy, szczególnie, ale nie wyłącznie, w Kościele katolickim oraz wielu innych nurtach chrześcijańskich.

Części trzecia do piątej pokazują szczegółowe przypadki egzorcystów w szeroko pojętym religijnym świecie, a więc odpowiednio w odnowie charyzmatycznej, ekstremie prawicowej protestantów oraz protestantach ewangelicznych. Wskazuje się tutaj także na prowadzone badania jak ci ministrowie protestanccy, pod wpływem trendów terapeutycznych, wpisują się w szeroko pojętą współczesną kulturę, także bez wyraźnie akcentowanych wartości religijnych czy wręcz chrześcijańskich.

Natomiast ostatnia, tj. część szósta podaje oficjalne przypadki oraz i jakby podziemne znaki egzorcyzmów praktykowane w katolicyzmie amerykańskim. Taki obraz w całej proponowanej pracy to efekt ponad dwóch lat pracy i także udziału w egzorcyzmach czy liczne rozmowy z różnymi osobami (s. XV).

Już u samego początku wszelkich analiz warto tutaj pamiętać, że przełomowym elementem w kwestii spojrzenia oraz dyskusji nad problematyką egzorcyzmów był film W. P. Blatty The Exorcist z 1973 r. (oparty na jego książce z 1971 r.) oraz książka M. Martin Hortage to the Devil z 1976 r. Te dwa momenty otworzyły gotowość dyskusji wokół tych problemów, choć jednocześnie w swej specyfice ukierunkowały ją tak w zakresie formy jak i treści.

M. W. Cuneo wyraźnie wskazuje, że problematyka egzorcyzmów szczególnie intensywnie występuje we współczesnej Ameryce nie tylko w Kościele katolickim, ale także i w innych Kościołach chrześcijańskich, zwłaszcza protestanckich, i to najnowszej proweniencji. To istotne wskazanie na ważne zjawisko, które dziś przybiera na sile i ma coraz więcej zewnętrznych znaków nie tylko religijnych.

Dobrze, że M. W. Cuneo ma świadomość, że szeroko pojęta problematyka egzorcyzmów to niejednokrotnie swoista forma współczesnego bissnesu oraz bardzo powierzchownego ich odczytania ukierunkowanego tylko na korzyści ekonomiczne. Zauważyć można zatem – zwłaszcza m.in. w tym kontekście -, że aktualna refleksja, aby poprawnie zrozumieć kwestie egzorcyzmów winna być bardziej twórczo otwarta ku bogactwu każdego człowieka, oraz jego wspólnot, i to w wielorakości wszelkich jego relacji oraz odniesień.

Czytając prezentowaną książkę warto pamiętać, że oparta jest na wielu osobistych wywiadach także z licznymi egzorcystami i ich wieloma klientami oraz także w oparciu o interesujące obserwacje oraz przemyślenia, i to z pierwszej ręki z ponad 50 egzorcystami. Oczywiście taka baza źródłowa jest ważnym, pozytywnym argumentem źródłowym w prezentacji podejmowanej tu problematyki.

Co więcej, w tym właśnie kontekście, autor pracy badawczej słusznie zapewnia, że wszystkie dane w sferze badawczej są prawdziwe, mając jednocześnie na względzie swe podstawy w prowadzonych badaniach oraz prowadzonych studiach nad chrześcijaństwem przełomu czasów (s. XIV). Wydaje się jednak, że tak bogaty oraz wszechstronny materiał ma jednak swoje przekonujące argumenty źródłowe. Nie są one jednak w pełni przekonujące i twórcze.

Książka amerykańskiego profesora, jak to zresztą sam wskazuje, ma dwa podstawowe zadania. Ma ona najpierw opowiedzieć historię realnego życia oraz zaangażowanych w to osób praktykującym egzorcyzmy w USA. Natomiast drugie przesłanie książki to przebadanie wielorakich dróg, na których różne kultury pomagają w inspiracji i popieraniu osób świadczących egzorcyzmy, pojętych jako swoiści ministrowie tych działań (s. XIV).

Prezentowana książka to bardzo interesujący kulturowy komentarz, a nie ostateczna ocena zjawiska egzorcyzmów (s. XIV). Fenomen ten wymaga także spojrzeń z innej strony, a zwłaszcza teologicznej oraz dyscypliny kościelnej. W tej jednak dziedzinie można zaobserwować dużą wstrzemięźliwość.

Ogólnie książka amerykańskiego badacza pokazuje współczesne znaczenie fenomenu egzorcyzmów, tak w sensie historycznym, psychologicznym jak i socjologicznym. Tak bogata i szeroka płaszczyzna jest znakiem pewnego obiektywizmu badawczego. Nie mniej jednak prezentuje sobą znaczące słabości, wręcz braki i błędy w płaszczyźnie teologicznej. Autor wręcz zdaje się często zupełnie nie dostrzegać tego wymiary. Jednak jego pominięcie to zupełne wypaczenie samego fenomenu oraz odejście od szansy jego poprawnego rozeznania oraz zrozumienia.

Zamieszczony na końcu indeks prezentuje tak elementy personalne jak i rzeczowe.

Warto zauważyć, że dość obszerne przypisy są nie tylko klasycznymi odniesieniami bibliograficznym. Zamieszczono w nich bowiem także liczne wyjaśnienia oraz uzupełnienia i dopowiedzenia. Zauważa się bardzo szerokie odwoływanie się do codziennej prasy. Czasem podaje się informacje i różne dane anonimowe, ale odnoszące się faktycznie do niezidenyfikowanych przypadków (s. 287, 291, 294, 299). Jednak oparcie się na prasie codziennej w znacznym stopniu obniża wartość merytoryczną książki. To uleganie danym, które zazwyczaj nie mają głębszych uzasadnień oraz motywacji, wymagają one bardziej pogłębionych badań i studiów.

Trzeba wskazać, że w rozdziałach 6 , 9, 11, 14, 15 używane są liczne pseudonimy lub zmieniono inne dane identyfikacyjne osób oraz różnych innych elementów. Faktycznie jest to dopuszczalne, ale praktycznie to także jeden z kolejnych elementów osłabiających wiarygodność treściową książki.

Natomiast wręcz swoistym dziwactwem jest informacja o leczeniu homoseksualizmu egzorcyzmami (s. 224-225). Jednak tendencje kulturowe w USA zdają się i to tłumaczyć oraz usprawiedliwiać.

Jako znaczący brak całej refleksji zauważa się zupełne pominięcie nauczania Jana Pawła II, który tak wiele razy nawiązywał do tej problematyki, tj. osobowej kwestii złego ducha jak i jego działania. Podobnie szkoda, że autor nie cytuje wskazań „Kodeksu Prawa Kanonicznego” oraz nauczania „Katechizmu Kościoła Katolickiego”, a więc szczególnie ważnych wskazań obowiązujących dla całego Kościoła katolickiego. Wyraźnie zauważa się także brak odniesień do „Lambeth Conferences” oraz wypowiedzi innych nurtów chrześcijańskich. Taka postawa wyraźnie świadczy o spłyceniu i zupełnym niezrozumieniu problemu egzorcyzmów, a faktycznie osobowej rzeczywistości złego ducha. Widzenie w egzorcyzmach tylko fenomenu kulturowego, to spłaszczenie działania złego ducha, to jakby owoc jego działania.

Wręcz kuriozalnym jest w rozdziale jedenastym w części czwartej wskazanie na specjalne demony rzymsko-katolickie, demona antysemityzmu, nietolerancji, seksualnych perwersji czy rzymskiego katolicyzmu. Takie sformułowania wydają świadectwo o samym autorze oraz jego generalnych założeniach w proponowanej książce. Te informacje zdają się podważać powagę całej pracy i wyraźnie wskazują na ideologiczne przesłanki proponowanych treści.

Natomiast rozdział dwunasty zawiera wiele elementów antyklerykalnych. Są to jednak pewne określenia i sformułowania, które być może w sensie ideowym są dalekie dla autora ksiązki. Użytku tutaj język jest bardzo negatywny, zwłaszcza wobec struktur kościelnych oraz nosi w sobie znaki wypaczonego czy błędnego obrazu tych elementów chrześcijaństwa (s. 182-183, 191-192).

Śledząc wiele informacji o zjawiskach religijnych czy kulturowych odnoszących się do kwestie egzorcyzmów można zauważyć w tej dziedzinie wiele pozytywnych bogactw, ale jednocześnie także wypaczeń. Przykładowo jednak ciekawym zjawiskiem jest, że wiele osób w Północnej Dakocie związanych jest z Scandinavianspiritism (s. 196-198). Fenomen ten, obok wielu innych, świadczy o otwartości, a jednocześnie i łatwości, szerokich wpływów opartych na motywach religijnych, które jednak faktycznie mają zupełnie inne przesłanki.

Dobrze, że autor wskazał m.in. na wielkie dziwactwo, które ukazało się w związku z telewizyjnym egzorcyzmem dziewczyny o imieniu Gina w programie „20/20” (s. 61-63, 65-66, 160, 243, 267). Okazuje się jednak, że tak oczywiste nadużycia nie mają wyraźnego przełożenia praktycznego w konkretnych postawach Amerykanów. Istnieje bowiem niezwykle silna postawa osobowego zaangażowania, która nie ma odniesień do negatywnych przykładów; po prostu nie są one znakami refleksji decyzyjnej.

Ciekawym wnioskiem jest stwierdzenie autora, że idealnym egzorcystą katolickim jest ten kto nie chce nim być (s. 268). Wydaje się, iż stwierdzenie to niesie w sobie wiele pozytywnych treści i jest w pewnym sensie uzasadnione. Nie można tutaj bowiem ulegać pewnym odczuciom czy rozeznaniom dalekim od wiary i jej świadectwa.

Śledząc historię problematyki egzorcyzmów można zauważyć w Kościele katolickim dużą wstrzemięźliwość czy wręcz dyskrecję. Dostrzeganie czy wręcz uświadamianie faktu wymagało zawsze czasu ku oficjalnemu rozeznaniu. Warto dodać, iż np. w Chicago w ponad 160 letniej historii lokalnego Kościoła pierwszy egzorcysta powołany został dopiero w ostatnich latach. Natomiast w Nowym Jorku, w ostatnim czasie poddano specjalnym badaniom 4 księży, którzy prowadzili działania egzorcystyczne od 1995 r.

Książka M. W. Cuneo stara się patrzeć od wewnątrz na fenomen relacji między religijnością rytualną i popularną kulturą. Zaproponowany obraz może jednak budzić wiele pytań czy wątpliwości. Wydaje się bowiem, iż książka jest zbyt jednostronna, jakby odpowiedzią na kulturowe zapotrzebowania środowiska amerykańskiego. Pójście po linii kulturowej czy socjologicznej nie może do końca tłumaczyć zjawisk religijnych oraz licznych wyrazów wiary i postaw świadectwa. To uleganie pewnym tendencjom, które starają się czysto racjonalne wytłumaczyć obserwowane zjawiska.

Oczywiście w tym szerokim kontekście pozostaje ciągle aktualnym pytanie o zagadnienie egzorcyzmów, tak w Kościele katolickim jak i chrześcijaństwie. To ostatecznie pytanie o fundamentalne spotkanie człowieka ze złym duchem, oraz sferę jego wielorakiego oddziaływania indywidualnego oraz wspólnotowego.

Little White Lies Magazine (London)

“The Exorcist” and the eternal struggle between religion and science

By Lara C Cory

[excerpted]

“The story is so utterly theatrical” says John Pielmeier “I mean what’s more dramatic than a life-and-soul struggle that takes place in a child’s bedroom?” In 2008 William Peter Blatty gave playwright John Pielmeier the rights to the stage production of his 1971 novel ‘The Exorcist’. The show opened at the Geffen Playhouse in Los Angeles in 2012 to mixed reviews. After a major re-write, and securing the efforts of celebrated director Sean Mathias, The Exorcist will make its west end debut in London this October.

In 1973, exorcism was an anathema in an increasingly secular western society. In 2017, despite an unlimited access to information, the crisis of faith rings truer than ever for many. In March, the Catholic News Agency reported that, “there is an alarming increase in demonic activity.” Exorcist for the Archdiocese of Indianapolis, Father Vincent Lampert believes that while steps are being taken to increase the number of exorcists, demand is still outpacing supply. According to Lampert and the International Association of Exorcists, “there is a great need for more exorcists.”

One private exorcist practitioner told The Economist that business is thriving in France “following the terrorist attacks in France late in 2015”, while sociologist Michael Cuneo, author of ‘American Exorcism’, believes that “exorcism is more readily available today in the United States than perhaps ever before.” Elsewhere The Telegraph has reported that “in the US, over the past 10 years, the number of official priest exorcists has more than quadrupled from 12 to 50.”

Saturday Night Magazine (Canada)

By Anne Collins

THE ABORTION DEBATE. It’s a wonder that we still describe it as such when neither side can bear to listen to the other’s arguments and no one ever really wins. Things that look like victories – to the pro-choice, for instance, the striking down of Canada’s old abortion law by the Supreme Court in 1988 – soon become grounds for new battles. Both sides had criticized the old law as a bad law, a typical Canadian compromise that neither put the decision squarely in a woman’s hands nor forbade her to abort. But after a summer of ex-boyfriends seeking, and even winning, injunctions and anti-abortionists practising passive resistance in the arms of police officers in front of the country’s abortion clinics, to some even the old law looks good. The call is once again going out to federal legislators to create some kind of law, a “typical Canadian compromise” that won’t please activists on either side but that the rest of the country can live with.

In that reasonable if amnesiac call for compromise is buried a profound misunderstanding of the abortion debate: that it is a political issue that will be amenable to a political solution. The quickest antidote to that idea may be to read Michael Cuneo’s new book, Catholics Against the Church: Anti-Abortion Protest in Toronto, 1969-1985. In early 1985, Cuneo set out to document both pro-choice and anti-abortion protest in Toronto, the epicentre of the controversy in English Canada since a Morgentaler Clinic first opened its doors there in 1983. But Cuneo soon abandoned the pro-choicers; he found story enough in the lay Catholics of the anti-abortion movement. His book is a fascinating account of how that movement, over the course of two decades, slowly turned on itself to eliminate “impure moderates” and present its most intransigent face to the world. Its target now, claims Cuneo, is as much the hierarchy of the Canadian Catholic Church as it is those who procure or perform abortions. It has evolved from a movement that would have settled for political reform to one that is on a “sacred crusade” to purify both the culture and the Catholic Church.

The common prejudice about anti-abortionists is that they are minions of the Catholic hierarchy. In the U.S. that prejudice has some basis in fact. After the American abortion law was struck down in 1973, the Catholic bishops moved to fund and organize a protest movement, right down to organizing at the parish, diocesan, and state levels political-action committees dedicated to elect anti-abortion candidates to office. In Canada, however, the Church has never been the driving force behind the movement; lay Catholics may have formed its largest contingent, but the hierarchy has for the most part kept its distance. The institutional Church has donated office space and services to local right-to-life organizations, allowed them to use the parish networks to get the word out, and left it to the discretion of priests to make small gifts of church money to the cause. But the Church has not funded the movement, lobbied the politicians, or even offered much of a public blessing; relatively few priests and nuns get out on the street when a demonstration is called.

It’s not that the Church hierarchy believes abortion is all right (though there is a group of “Catholics for choice”). It’s just that too heavy an emphasis on the abortion issue doesn’t suit the Canadian Church’s agenda in this undeniably secular age. The die was cast in the late 1960s, as Cuneo points out, by the Church’s attitude to the decriminalization of contraception: one of the bishops’ statements to Canadian politicians read, “that which the Church teaches to be morally reprehensible should not necessarily be considered as indictable by the criminal code of a country.” The modern Church is driven by a desire for political action on issues embraced by its “social gospel” – unemployment, poverty, war, human rights – but shies away from the political when it comes to private morality. Cuneo perceives, sharply enough, that to the Catholic bishops, abortion is too Catholic an issue; stringent statements from Catholic officials on ensoulment, sex, and murder could upset the delicate and much-lauded ecumenical balance achieved with Canada’s other Christian Churches through the 1970s and 1980s.

At first there was little conflict between anti-abortionists and their Church because they shared similar strategies and attitudes about bridge-building with a secular society. The early Catholic lay activists modelled their protest against abortion on civil-rights battles, and believed that if the facts were only known they could create a consensus on the status of the fetus. Science, they argued, was making it compellingly obvious that personhood attached to life from the moment of conception. They were patently not fanatical or right-wing. Martha Crean, for instance, who helped found the Coalition for the Protection of Human Life, the early political lobby group, was a model of reason and compassion, interested in “saving who we can.” That meant demanding the provision of more daycare and more support for low-income mothers as well as lobbying against abortion; as Crean said, “I’m not interested in condemnation” which “slam[s] the door on dialogue, on people’s fingers, in fact.” But Crean and others who shared her consensus-seeking approach were purged from positions of power in the movement in the late 1970s by a new breed of activist who found reasonableness an affront. In 1978 the Coalition was shoved off centre stage by the birth of another political organization, Campaign Life, which preferred to practise all-or-nothing politics rather than seek a compromise.

Both the old civil-rights supporters and the new leaders of Campaign Life shared a bleak worldview: in short, that the late twentieth century had gone to hell in a handcart. But the civil-rights supporters thought that they could chip away at the dross, that they could mitigate the circumstances that were forcing women to choose abortion – in other words, that there were pressing, comprehensible reasons that drove women to abortion and that these conditions had to be fixed before a legal ban could be orchestrated. On that score, Campaign Lifers were all attitude: abortion was the symbol of a world gone sour; only obdurate all-consuming resistance to the very idea of abortion would create the appropriately symbolic response. If you scratched the surface of such long-time activists as the Toronto lawyer Gwendolyn Landolt and Laura McArthur, who headed up the Right to Life Association of Toronto and Area, you found not so much an idea of how to move forward but a longing to go back – into a 1950s-nostalgia world in which everyone accepted that a family was nuclear, a woman looked after her children, and a man looked after her. Crean and others like her (still active, if low-profile, anti-abortionists) viewed themselves as feminists; Landolt and several other core women of the Campaign Life ilk in the 1980s formed the pro-family, anti-abortion, anti-feminist group REAL Women.

When I researched the movement in 1983 and 1984, I recognized its nostalgia, its anti-feminism, and its absolutism, but I missed the elements of true-believing Catholicism Cuneo says now defines the movement. I noticed that the Campaign Life newspaper, The Interim, hit its bitterest notes when it derided Catholics it decided were soft on abortion, but I also noticed that even the hard-bitten fighters at Campaign Life found the Catholicism of Joe Borowski, the former Manitoba NDP cabinet minister turned anti-abortionist, somewhat embarrassing. In 1981, Borowski had fasted into the realm of religious visions and near-death to protest the fact that the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms did not intend to recognize the fetus as a person; only a phone call from the pope’s Canadian emissary deterred him at the eighty-day mark. Borowski was willing to get himself arrested, to stake thousands of dollars on a court challenge on behalf of the fetus (since failed, at the Supreme Court level), to bear witness in front of clinics, to call himself a prophet in his own land. A few years ago, it was easy to describe him as a maverick within the movement; it’s not so easy now.

Borowski would meet many kindred spirits on the picket lines in front of the two abortion clinics in Toronto, where Michael Cuneo spent time as an academic “participant-observer.” Seventy percent of the picketers were Catholic and of them the majority were what Cuneo has called “Catholic revivalists”; he similarly categorized the largest proportion of the 111 activists he interviewed. The new lay activists are out of step with the Church – betrayed, they say, by a clerical hierarchy and intelligentsia that won’t act on abortion. Though some of these revivalist Catholics are well under thirty, they trace this betrayal two decades back to Vatican II, when the Church attempted to democratize itself to face the modern age. A large group of the picketers Cuneo interviewed are converts to Catholicism or had strayed and then come back to a Church they found too relative for them. They want an all-or-nothing Catholicism, ultramontane, infusing every aspect of their lives – not a Church that gives their consciences back on a platter. They sought religious intensity and commitment, and found the anti-abortion movement. In their view anti-abortion protest separates the wheat from the chaff of the Church – and they are the wheat. Where others might eventually quail at the opprobrium heaped on them by passers-by, revivalist Catholics view the picketing and civil disobedience as acts of witness that bond them with others who are also true believers. As one of them told Cuneo, “What you see here is the remnant. The phoenix will rise from people like this. The Church is alive and well here. I think the Church will be stripped to its bare bones and will be made up of only the true believers who’ll put their lives on the line for the faith.” In their minds, the pro-life movement has become the prototype of a reborn Church.

Much of Michael Cuneo’s energy is spent documenting the sway these revivalist Catholics now have on the movement, and their war with the Canadian Catholic Church. As he announces in the introduction of the book, he’s academically determined to stay neutral on the issue of abortion; he spends no time speculating on how the new Catholic fervour will affect the politics of abortion. Since the rise of Campaign Life, few mainstream anti-abortionists have had any respect for or understanding of their opposition; their attitude to women “in trouble” has been at best charitable, at worst punitive. If the movement now so vitriolically writes off “soft” Catholics, will it ever have any time for the “other side” – the embodiment of “evil”?

From the evidence in Cuneo’s book the hardliners are certainly not operating in a pragmatic mode where they could consider any solution to the crisis other than an absolute ban. The revivalist Catholics he describes are too busy being “religious athletes” – picturing their martyrdom – to think about the realities of abortion. In a chapter of portraits of the activists, Cuneo quotes every revivalist as being willing to be martyred for the cause. How they intend to do that leaves the mind spinning.

The one distinction on which I’d quibble with Michael Cuneo is attaching the word “sacred” to the current anti-abortion crusade; spiritually, these activists are orthodox foot soldiers, not holy men or women. Until the true believers graduate even to the level of religious faith (where doubt is always a partner), compromise on the abortion issue is a chimera. No political solution will soothe the souls of the true believers.