Contents

Publishers Weekly — The Year in Books

Arizona Republic (Phoenix) — Big Books

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution — Books Preview

The Kansas City Star — Almost Midnight Tells Tale of Murder and Mercy in Missouri

The New Yorker — The Devil Inside

The Times (Trenton, NJ) — Bell, Book and Candle

Booklist — American Exorcism

Kirkus Reviews — Almost Midnight

The Post and Courier (Charleston, SC) — Varieties of Satanic Experience

Alibi (Albuquerque) — American Exorcism

The Tampa Tribune — Catholics Fear Implosion

Book Magazine — American Exorcism

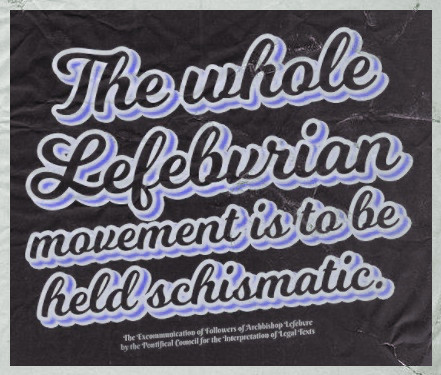

Kirkus Reviews — The Smoke of Satan

Catholic New Times — Cuneo presents balanced view of abortion issue

Daily Chronicle (De Kalb, IL) — American Exorcism

West Coast Review of Books — American Exorcism

The Christian CENTURY — Catholics Against the Church

America — The Smoke of Satan

Skeptical Inquirer — A Sociologist’s Journey into the American Heart of Darkness

The Catholic Register — Catholics Against the Church

Word Trade (Chapel Hill, NC) — The Smoke of Satan

Religious Studies Review — Catholics Against the Church

Millennial Stew — The Smoke of Satan

Choice — Catholics Against the Church

Good Reports — American Exorcism

curledup.com — Almost Midnight

The Canadian Catholic Review — The Revivalist Vision of the Church

Free Inquiry Group — American Exorcism

Studies in Religion / Sciences Religieuses — Catholics Against the Church

The Hopewell Christian Educator — God, Pentecostals and the Pope in the Ozarks

Times of Acadiana (Lafayette, LA) — Exorcisms, Demons, and American Culture

Kirkus Reviews — American Exorcism

Hartford Advocate — Deliver U.S. from Evil

Publishers Weekly — Almost Midnight

Library Journal — American Exorcism

Publishers Weekly

THIS IS THE debut of PW’s “The Year in Books,” an annual review examining noteworthy trends in books and publishing. This approach includes highlighting titles that we discern to be of exceptional quality.

• RELIGION

“Buddha,” by Karen Armstrong (Viking). Lacking details for a conventional biography, Armstrong turns this to her advantage, opting to enhance Gotama’s story with the broad canvass of his time and culture, making him accessibly human.

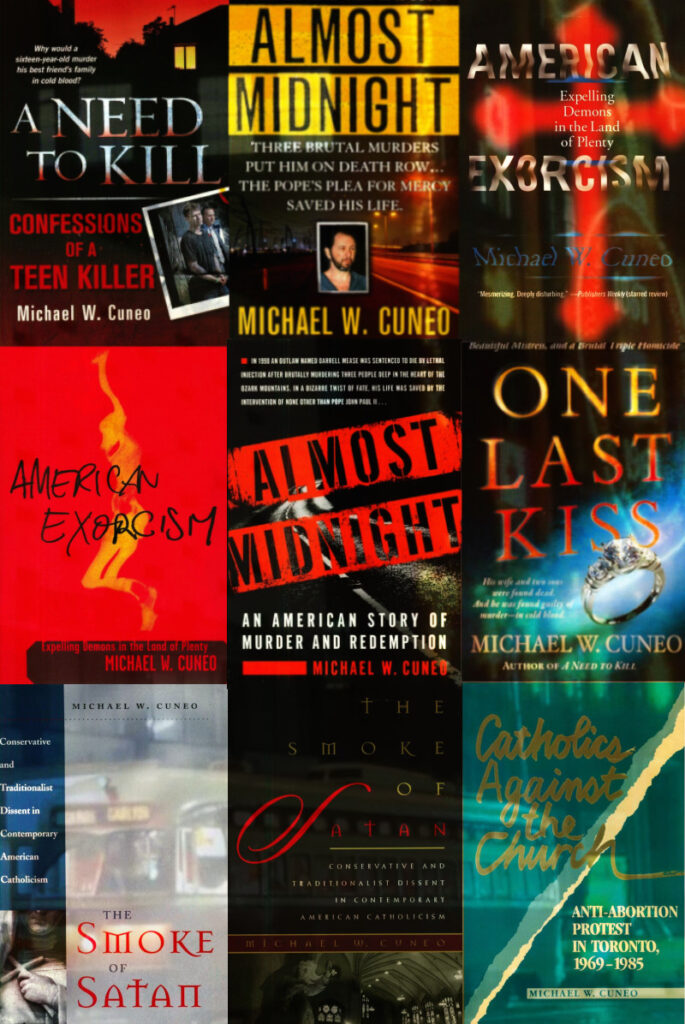

“American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty,” by Michael W. Cuneo (Doubleday). Lucidly written and riveting as any horror novel, Cuneo’s excursion into the darker paths of American faith offers a deeply disturbing, ironic vision of the unintentional consequences of popular culture for the modern religious imagination.

“A New Religious America: How a “Christian Country” Has Become the World’s Most Religiously Diverse Nation,” by Diana L. Eck (Harper San Francisco). Eck delivers a stunning tour de force that may forever change the way Americans claim to be “one nation, under God.” This is not just a book; it is a celebration.

Arizona Republic (Phoenix)

Republic staff

EACH YEAR BRINGS a throng of new books. We have assembled a panel of 13 people, including a librarian, an educator, a short-story writer, a poet and a critic or two, to identify this year’s most noteworthy.

• MYSTERIES/THRILLERS

“In the Night Room,” by Peter Straub. Enter at your own risk.

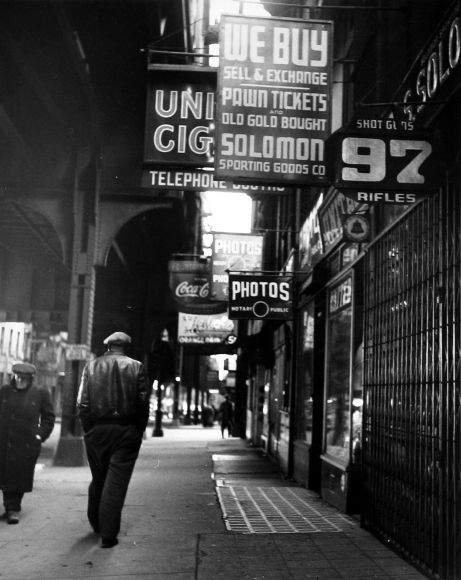

“Almost Midnight: An American Story of Murder and Redemption,” by Michael W. Cuneo. True (and truly disturbing) story of drugs and violence in Missouri’s Ozarks.

“Skinny Dip,” by Carl Hiaasen. Wetlands, crooks, wealth, a cruise.

“Destination: Morgue!” by James Ellroy. Searing nonfiction pieces make up for less interesting novellas.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

NONFICTION

● “Harvard Diary II: Essays on the Sacred and the Secular” by Robert Coles (Crossroad, $20). A Pulitzer Prize-winning author shares his observations. (April)

● “The Smoke of Satan: Conservative and Traditionalist Dissent in Contemporary American Catholicism” by Michael W. Cuneo (Oxford, $25). An assessment of right-wing Catholic groups and of militant anti-abortion activism. (May)

● “After God: The Future of Religion” by Don Cupitt (Basic, $20). The author traces the move from traditional belief to cynicism to faith after the so-called death of God. (May)

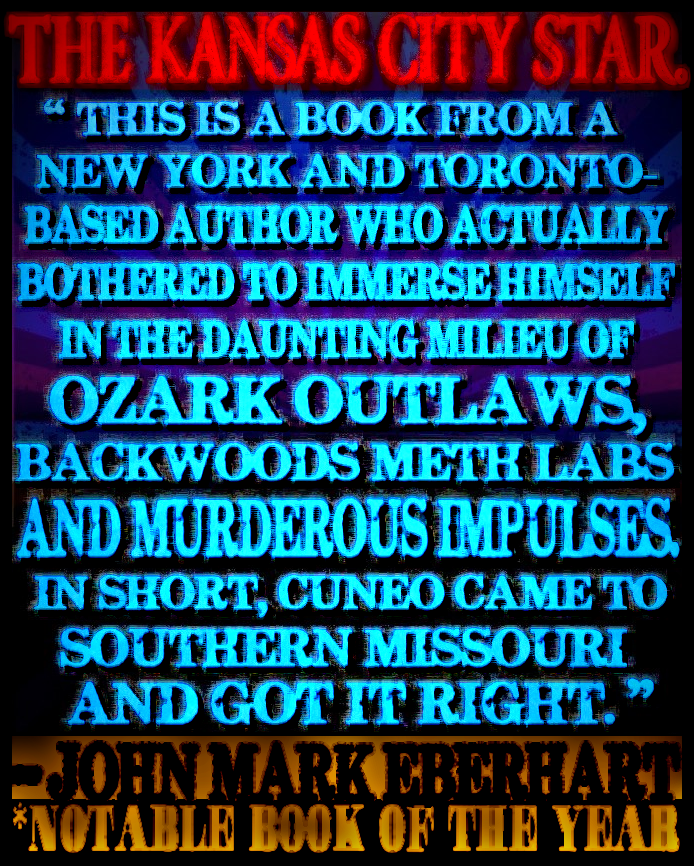

The Kansas City Star

Almost Midnight Tells Tale of Murder and Mercy in Missouri

By John Mark Eberhart

THE TROUBLE with the “true crime” genre: Its frequent extremism.

On the one hand, some of its practitioners engage in lofty literary pretensions: Norman Mailer trying to turn The Executioner’s Song into “a true life novel,” or Truman Capote getting his facts not quite right as he seeks the prose summit in the pages of In Cold Blood.

On the other hand we find countless titles that come dangerously close to being sleaze. Typically, these are quickly written, sensationally promoted or laden with lurid photos. Think of James W. Clarke’s Last Rampage or Don Davis’ The Milwaukee Murders, re-released in paperback as The Jeffrey Dahmer Story.

So it’s always great to find a well-balanced exception, such as Michael W. Cuneo’s Almost Midnight: An American Story of Murder and Redemption, a true-crime yarn built upon journalistic prose and solid research.

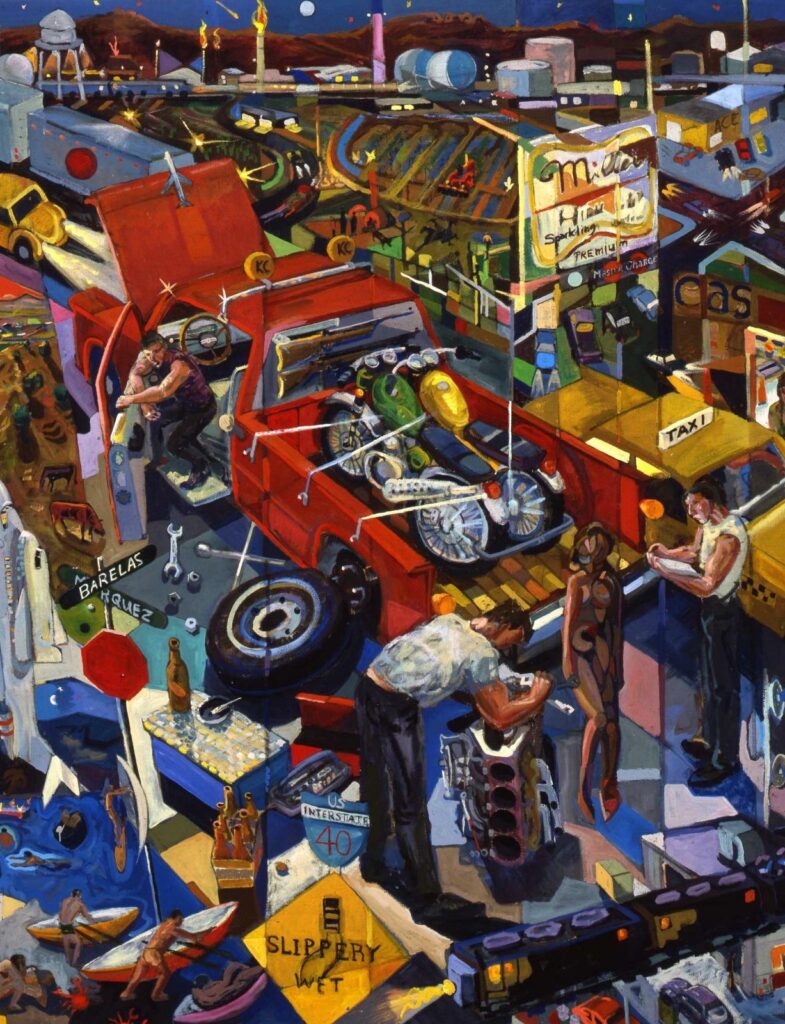

This is a book from a New York and Toronto-based author who actually bothered to immerse himself in the daunting milieu of Ozark outlaws, backwoods meth labs and murderous impulses. In short, Cuneo, despite being an outsider, came to southern Missouri and got it right.

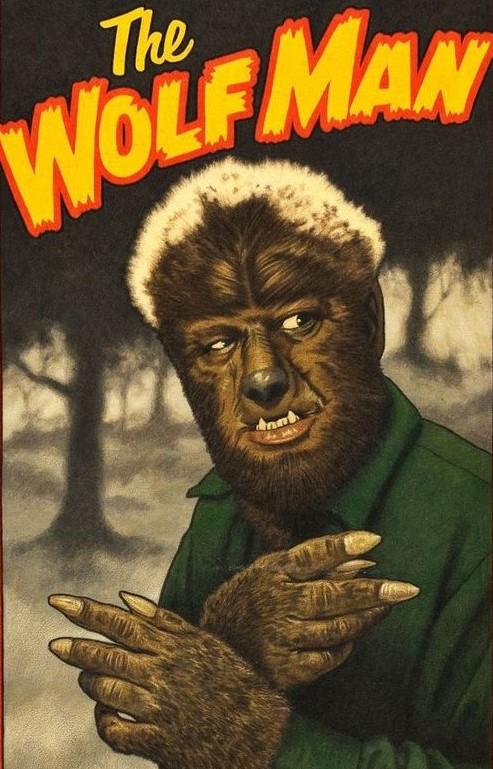

Almost Midnight chronicles the disturbing transformation of Darrell Mease. Mease was born in the late 1940s in Reed Springs, Mo., and his early life was rooted in Pentecostal religion, in the boyhood pastimes of hunting and fishing, in a lifestyle so squeaky clean that it didn’t even involve profanity.

As Cuneo writes, a tour of duty in Vietnam changed all that. When Mease returned to Missouri in the late 1960s, he came home as a young man beset by drug and alcohol problems. A turbulent marriage and a lack of any real career opportunities didn’t help matters.

Nor did the surroundings, nor the company Mease chose to keep. Cuneo’s depiction of Mease’s world is especially vivid:

“The Ozarks had always attracted outlaws, men and women who were out of sorts with mainstream society, who harbored deep grudges and had few if any bridges left to burn. The rough-and-tumble terrain, with its rugged bluffs, lost caves, and steep hillsides, afforded plenty of places for hiding out, digging in, making plans for that one last score, that one last run for happiness.”

By the late 1980s Mease saw that “one last run” as a partnership with Lloyd Lawrence, a man reputed to be setting up methamphetamine labs all over the hill country. Suffice it to say that the two men didn’t quite hit it off, partly because of Lawrence’s leering at Mease’s young girlfriend, Mary Epps.

Lawrence was no saint; because of his not-so-subtle threats, both Epps and Mease would fear for their lives — although in Mease’s case, part of the dread may have been based on his sampling of the meth, or “crank.” At any rate, the tension between the two men reached its peak in May 1988, when Mease hid out in the brush on Lawrence’s property, then shotgunned Lawrence, Lawrence’s wife, and the couple’s grandson.

Mease fled Missouri with Epps, and the couple spent much of their time in the American West, living as nomads, often down and out. When Mease finally was apprehended, he provided authorities with a videotaped confession.

Then things got weird.

In jail Mease turned to religion, but this was less a conversion than a return to the values imparted to him in his youth. Despite his 1990 conviction and death sentence, Mease’s faith convinced him he would not be executed.

He was right.

Mease was supposed to die in January 1999. That month Pope John Paul II, a strong opponent of the death penalty, visited St. Louis and pleaded with Gov. Mel Carnahan to spare Mease’s life. Only once had Carnahan commuted a death sentence, and that case had involved circumstances far more mitigating than anything Mease could bring to the legal appeals table.

But Carnahan granted the pope’s request. Mease’s sentence was commuted to life in prison without possibility of parole. Carnahan died the following year in a plane crash while campaigning for a U.S. Senate seat against John Ashcroft — and Missouri voters elected the dead man. Meanwhile, Darrell Mease remained incarcerated in Potosi Correctional Center, as he does today.

The story should end there — except that Mease’s faith seems to have no end. As Cuneo writes, Mease still believes he may be released from prison one day. Impossible? Consider Cuneo’s observation about how unusual the case already has been:

“Darrell Mease, one of the last true Ozark hillbillies, had become the first person in the history of the United States to have his death sentence commuted through the direct intervention of a religious leader from outside the country.”

Cuneo’s book, in addition to depicting southern Missouri so vividly, raises serious questions without presuming to know all the answers. Even death-penalty opponents would concede that mercy for Mease, while so many others have been executed, was arbitrary.

Gripping as it is, Almost Midnight has its shortcomings. The publisher has not seen fit to include an index. And, given the complex nature of the subject matter, a chronology would have been nice.

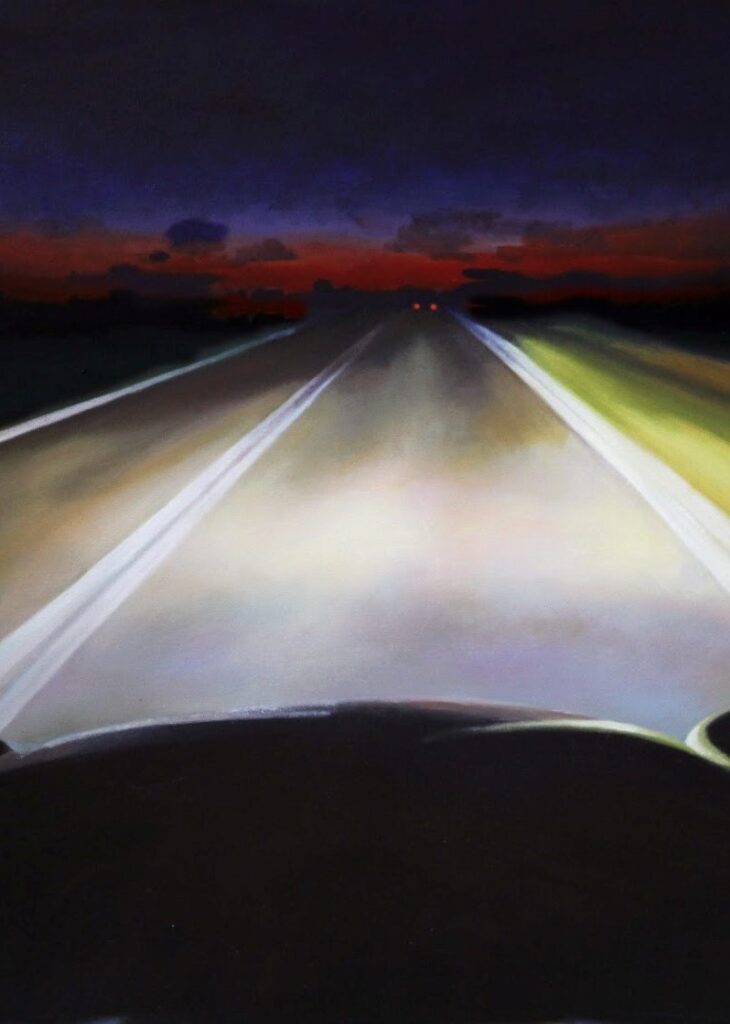

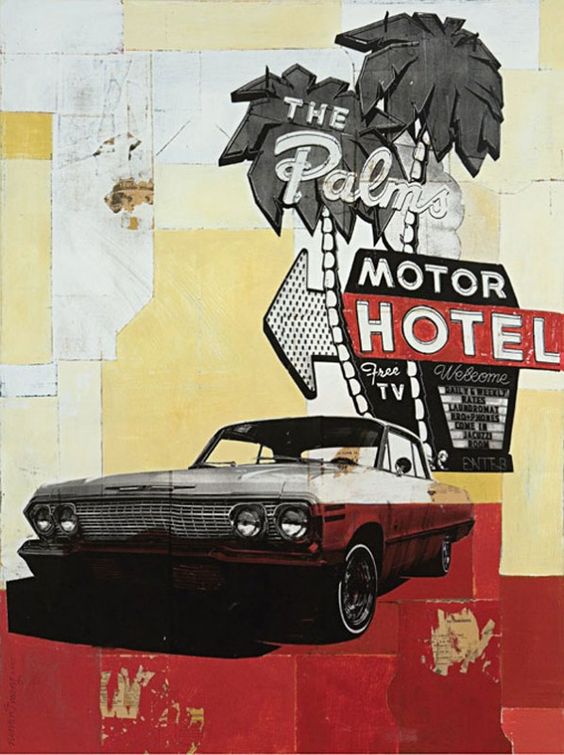

But the reading experience is undeniably potent, for Almost Midnight barrels along like a hot rod on a twisty Ozarks road. There are no photos here; Cuneo depends on his prose alone to provide the imagery.

And the author has kept up with how Missouri has changed; Cuneo’s observation that meth labs have gotten even more sophisticated, harder for law enforcement to detect (some of the labs are even mobile now) is sobering indeed.

Almost Midnight is a fast, furious read that leaves one plagued by disturbing thoughts every time one manages to pause before turning another page.

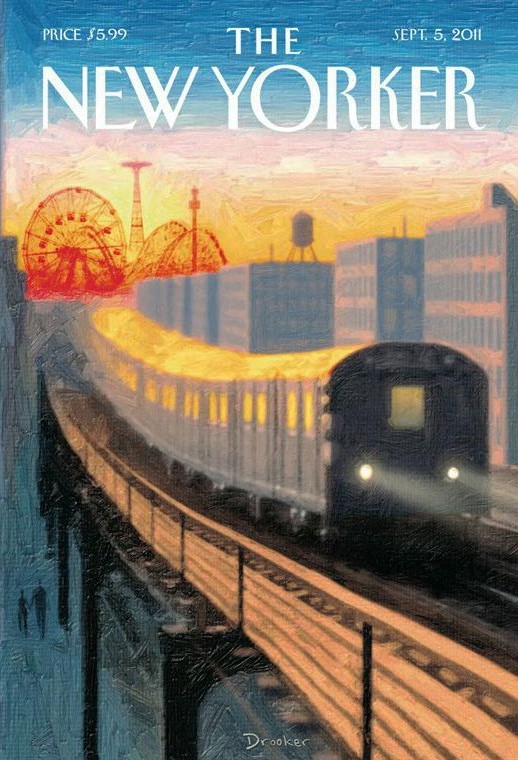

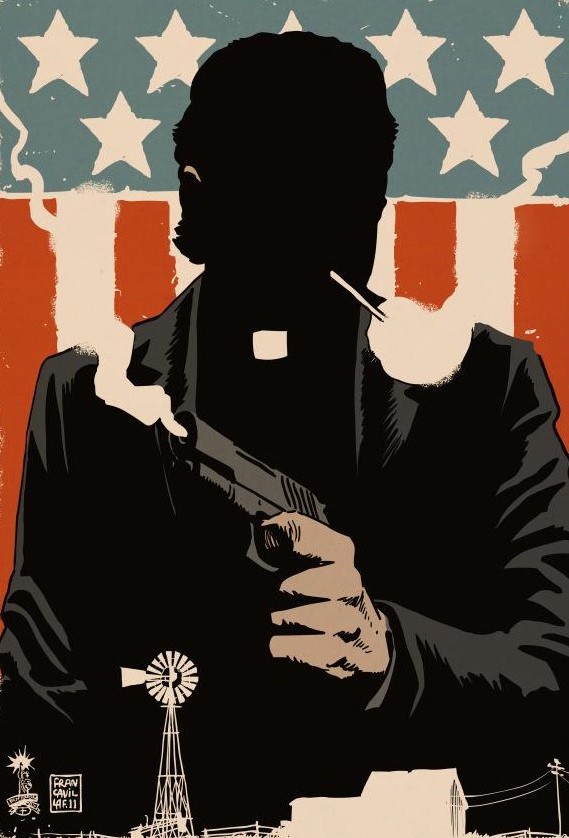

The New Yorker

By Mark Rozzo

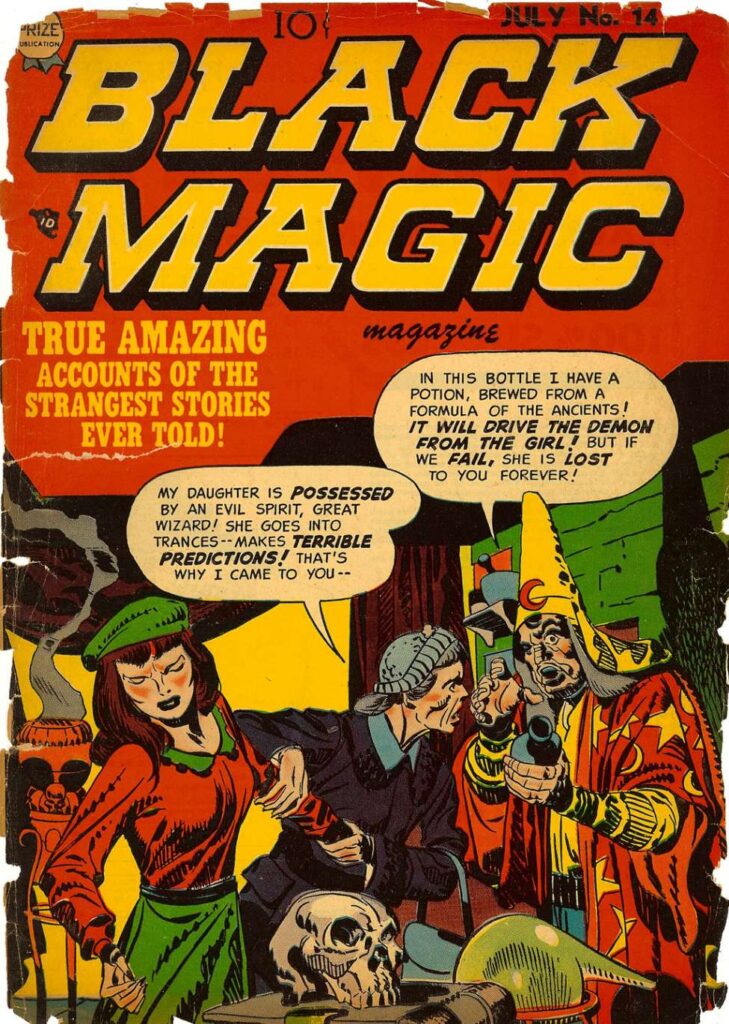

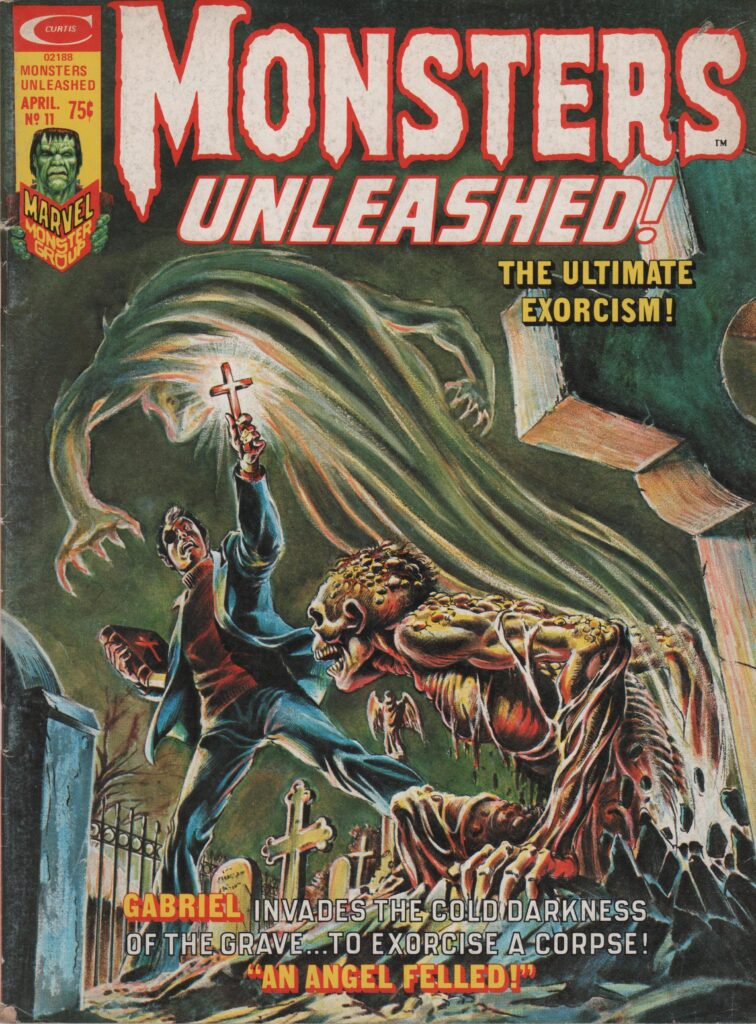

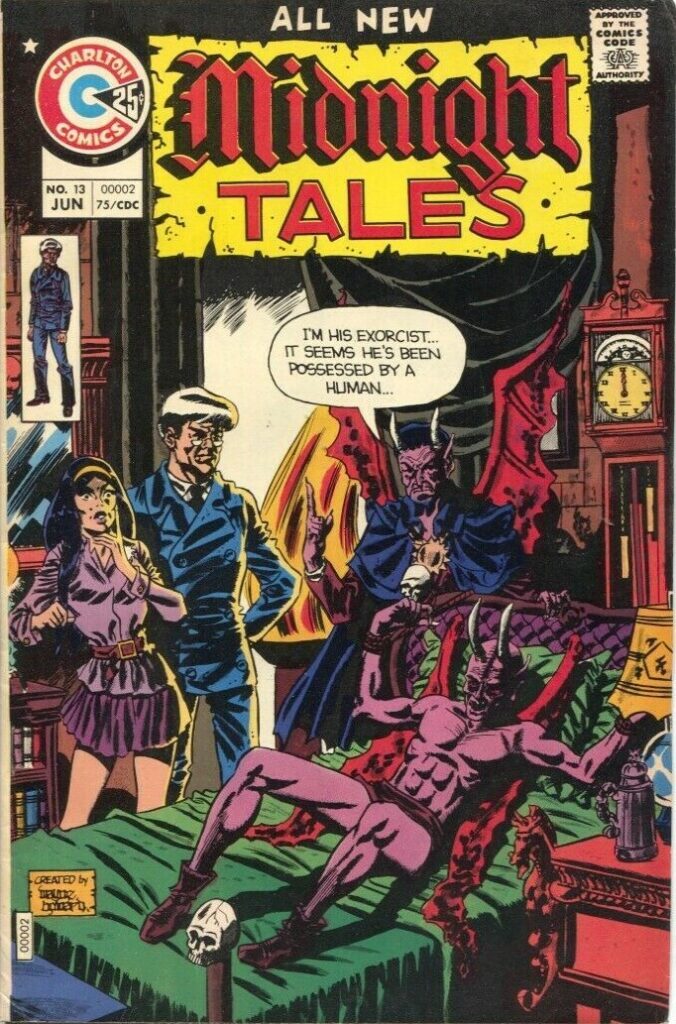

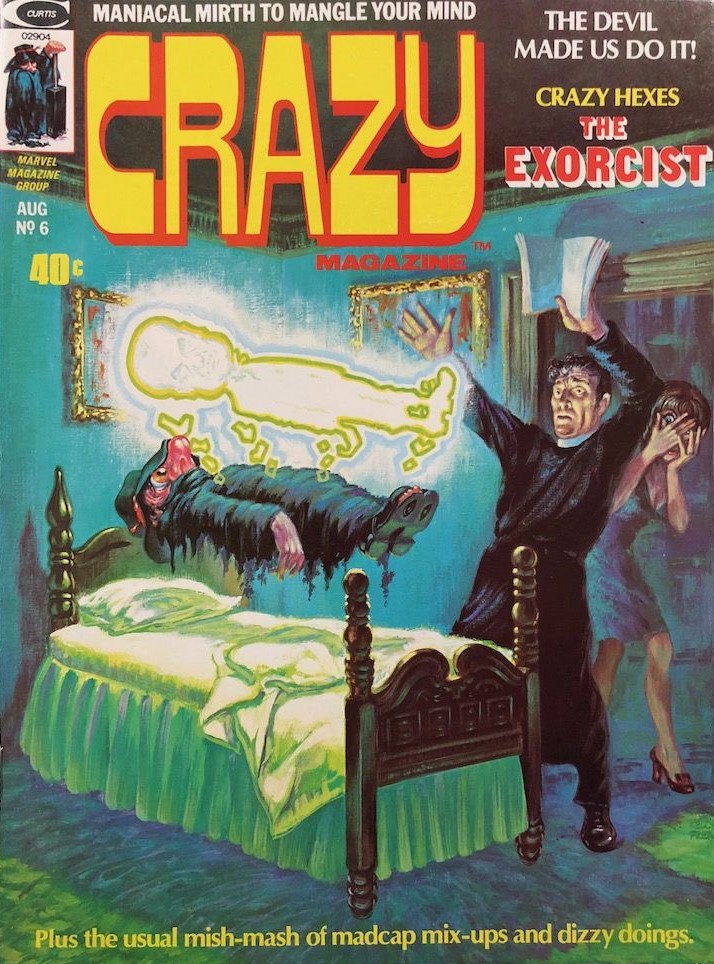

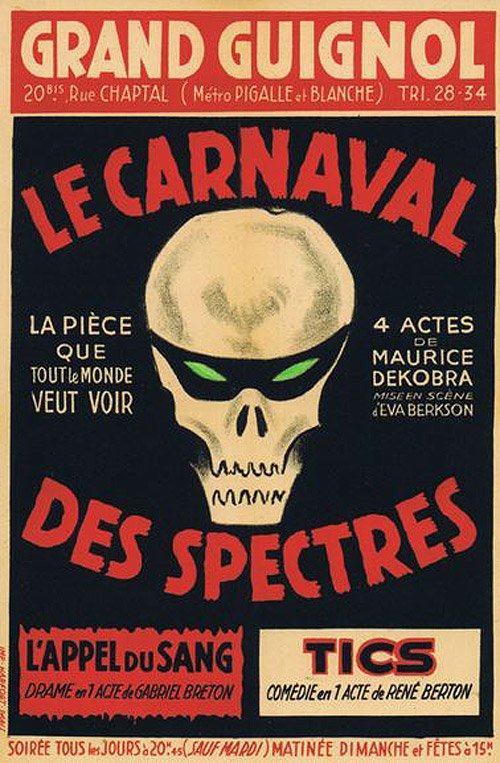

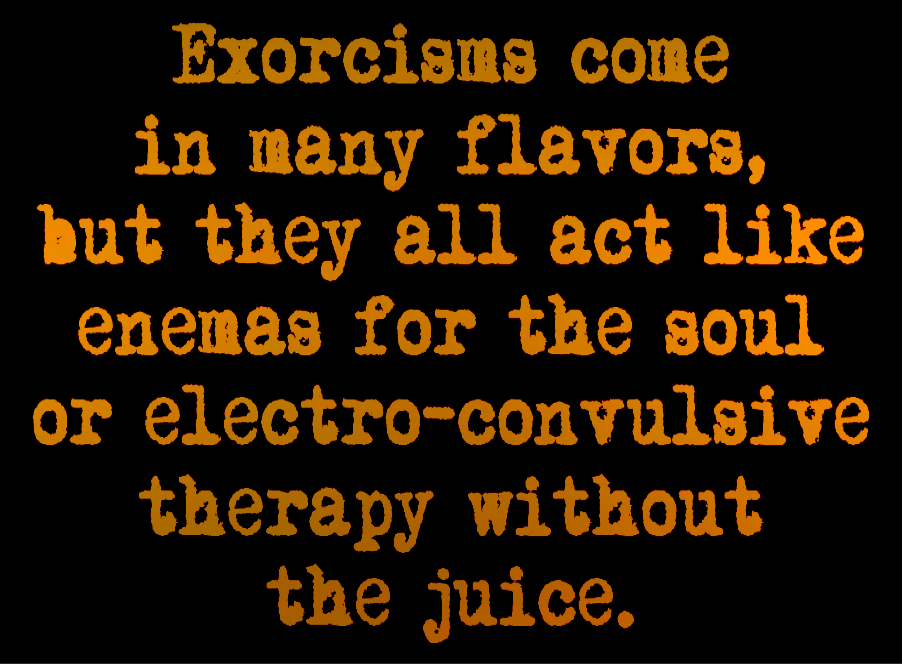

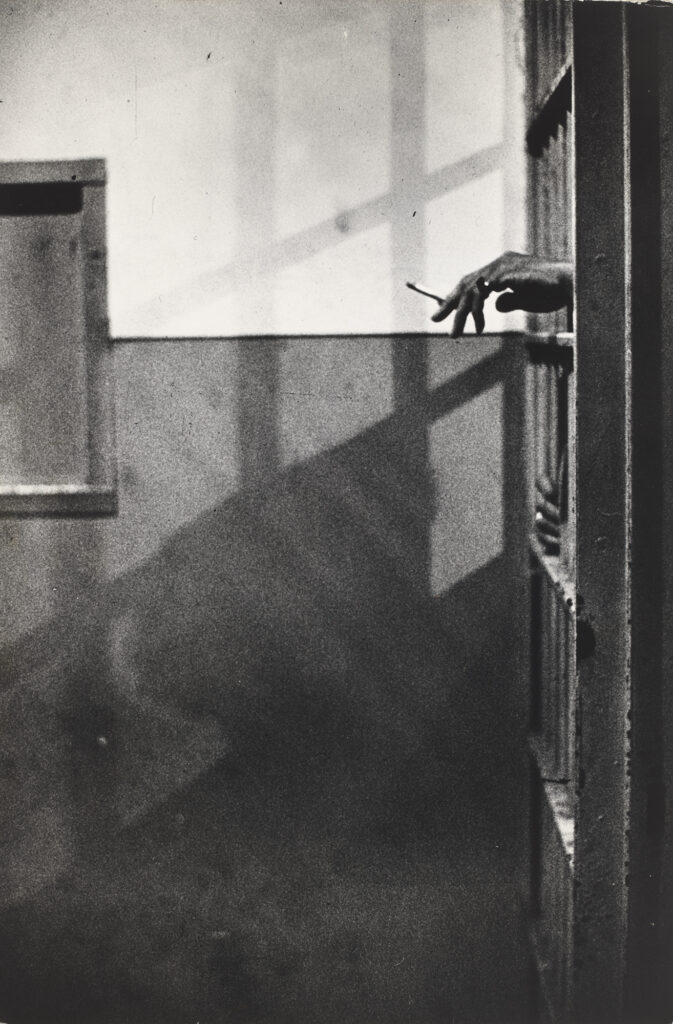

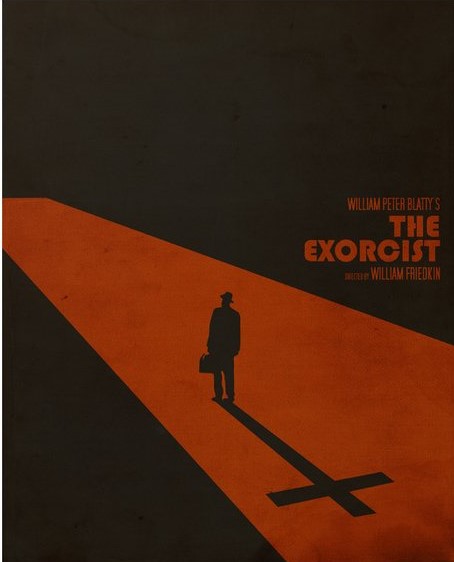

IN THE YEARS since William Friedkin’s 1973 horror extravaganza, “The Exorcist” – which was rereleased with considerable fanfare last year – the archaic rite of casting out demons has become more popular than ever. So argues the Fordham professor Michael Cuneo in his AMERICAN EXORCISM (Doubleday), a recently published history of the contemporary resurgence of exorcism and belief in demonic possession. Cuneo sat in on dozens of exorcisms, finding that these days the controversial procedure (typically scorned by Catholic officials) runs the gamut from Linda Blair-style “puke-and-rebuke sessions” to mellow suburban affairs attended by hot chocolate, cookies, and potato chips.

The Times (Trenton, New Jersey)

Bell, Book and Candle: Why Legions are Possessed by Exorcism

By Meredith Gould

THE AMERICAN FASCINATION with demons and their exorcism can be attributed to two landmarks of popular culture according to “American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty” (Doubleday, 314 pages, $24,95), Michael Cuneo’s examination of this surprisingly common phenomenon.

The first was William Peter Blatty’s bestselling 1971 novel “The Exorcist,” which was made into a blockbuster movie in 1973. A Washington Post article about an exorcism performed on an adolescent boy inspired Blatty’s heavily fictionalized account. The year was 1949, and Blatty, then an undergraduate at Georgetown University, became possessed by the story.

Next came the publication, in 1976, of Malachi Martin’s “Hostage to the Devil,” a lurid bestseller in which this former Jesuit priest described five contemporary case histories of possession and exorcism.

“Am I really suggesting,” writes Cuneo in his concluding chapter, “that the popular entertainment industry, with all its dreck and drivel, is capable of manipulating – actually manipulating – religious beliefs and behavior?”

In a word, yes.

Why, asks Cuneo, would we expect religious Americans to be any more immune to Hollywood’s charms than the rest of us? “The only surprise, in my view,” he continues, “is that scholars of religion in the United States have been so slow to make this connection.”

But the question remains: Do demons really exist? And does exorcism actually expel them? While Cuneo is more equivocal when it comes to these issues, let me just say that anyone who truly believes in demonic possession will find much to appreciate in “American Exorcism.”

Cuneo, a sociologist at Fordham University, spent two years studying exorcism ministries across the United States. He interviewed exorcists and deliverance ministers, as well as those who believed that they had been possessed by, then delivered from, evil. He witnessed the exorcisms of more than 50 people, as well as a number of group deliverances.

Apparently there’s no shortage of fodder for research these days. In New York alone, four Catholic Church-appointed exorcists have investigated approximately 40 cases annually of suspected possession since 1995. In America’s heartland, burgeoning charismatic deliverance ministries within Protestant sects have been casting out hoards of evil spirits from spirit-filled seekers since the 1980s. While most of us consider these rituals to be the domain of Catholic priests, Cuneo reveals that exorcism is embraced by many modern mainstream Pentecostals and evangelicals, as well. Indeed, sectarian nuances are many and complex, but Cuneo sorts it all out with sociological precision.

While no one levitated, broke out in “brandings” or morphed into a serpent before his eyes, Cuneo remains remarkably unwilling to declare it all a hoax. What he did – and did not – see makes for interesting reading, but what is more compelling is the case he makes for the potency of popular culture, the therapeutic value of a “placebo effect writ large,” and the simply brilliant proposition that exorcism could be considered a form of “alternative medical therapy for those who see demons, not cholesterol, not toxic particles, not environmental stress or genetic predisposition – no, not any of these, not primarily anyway – but demons, real glowering, hell-bent-on-evil demons as the major scourge of our time.” Given the American inclination to seek solace, if not illumination, through therapy, exorcism could certainly have its place in the bumper crop of contemporary treatments. Exorcism may be, says Cuneo, the “crazy uncle of therapies,” but therapy it is.

As its title suggests, “American Exorcism” is about the quintessentially American character of an ancient religious ritual. “Despite being cloaked in the time-orphaned language of demons and supernatural evil, deliverance was surprisingly at home in the brightly lit, fulfillment-on-demand culture of post-Sixties America,” the author observes.

Cuneo brings to his subject a delightful combination of respect, curiosity, irony and, not least, a humor that manages to be wry without being derisive. He has written one of the few books whose footnotes merit careful reading. This is sociology at its absolute best – rigorous field work conducted in the grand Chicago School tradition of participant and nonparticipant observation – and its findings are delivered with wit, wisdom and lucidity.

Booklist

Michael W. Cuneo ● American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty (Doubleday, $24.95)

By John Green

Michael Cuneo’s passion for all things bedeviled led him to write this remarkable book, a sweeping study of exorcism in contemporary America. His hypothesis? The popularity of exorcism, especially of the difficult-to-attain Catholic variety, is due in large part to William Peter Blatty’s novel The Exorcist and the popular film of it.

Cuneo traveled the country, witnessing every variety of demonic expulsion, from official Catholic exorcisms to large meetings in which demons of lust are called out of evangelical Protestants. Cuneo’s point of view, “open-minded skepticism,” is in truth more skeptical than open-minded, but the exorcisms he saw offered little to gainsay incredulity. Written at an ironic distance that permits laughter at some of the more absurd exorcisms (e.g., a man exorcised because he sometimes disagrees with his girlfriend), the book reads like a novel. It is a wonderfully astute and readable dissertation on pop culture’s manipulation of religion.

YA/L: A fascinating study of demonology for teen fans of The Exorcist and Buffy.

Kirkus Reviews

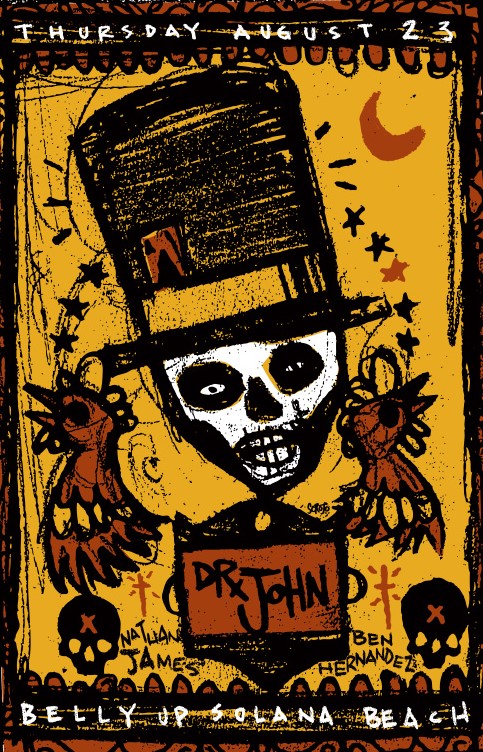

Almost Midnight: An American Story of Murder and Redemption

A strong true-crime tale with disturbing noirish undertones and undeniable spiritual flair

AN ENGROSSING EXAMINATION of an Ozarks triple murder and its strangely sympathetic perpetrator, who avoided execution via the pope’s intervention.

As in his American Exorcism, Cuneo methodically examines a tangled American subculture, rife with extremism and religious fervor. Here, he addresses the outlaw archetype that’s endured within southwestern Missouri culture, at odds with the milieu presented to the state’s Branson-bound tourists.

Darrell Mease was the most charming boy in Reeds Spring, Missouri, and his idyllic childhood bred within him the region’s strict Pentecostalism; yet Vietnam, failed marriages, and involvement in the Ozarks methamphetamine scene left him a fractured and paranoid man. Following disputes with feared local drug kingpin Lloyd Lawrence (whose ordinary lifestyle belied a brutal history, including the rape of his own daughters), Mease fled Missouri with stolen meth and with Mary Epps, whom he considered his true love; Lloyd then put out murder contracts upon both.

Cuneo argues that an unspoken code of Ozarks vengeance, developed in response to historically corrupt law enforcement, influenced Mease’s decision to return and settle accounts with Lloyd; in a shocking ambush, he shotgunned Lloyd, his wife, and handicapped grandson. After several months on the lam, Mease was captured and confessed in an attempt to protect Mary; following his 1989 conviction and death sentence, he experienced a jailhouse conversion, claiming that God would not allow his execution. Incredibly, the 1999 papal visit to St. Louis forced postponement of Mease’s execution date; after noting this, the Vatican indeed prevailed upon then-governor Mel Carnahan to commute Mease’s sentence to life. (Yet, Cuneo observes that Missouri’s pro-execution politics have since continued unabated.)

Cuneo is skillful at nailing down the elusive stories of warts-and-all heartland America; he does a fine job of untangling this complex affair’s ambiguities, in which idealized rural lifestyles collide tragically with the concentrated violence of both the drug war and state-sanctioned capital punishment.

A strong true-crime tale with disturbing noirish undertones and undeniable spiritual flair.

The Post and Courier (Charleston, South Carolina)

Varieties of Satanic Experience

A review of American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty by Michael W. Cuneo. Doubleday. 314 pages. $24.95.

By Rodney Welch

MY SOLE EXPERIENCE with demonic possession came sometime in the early 1970s, when one of my Southern Baptist preacher dad’s many eccentric preacher friends came through town. This one was a big fellow named Winifred Worley, about whom I recall almost nothing except that he claimed to see several demons sitting on the shoulder of my brother Tom. Tom can’t recall now whether Worley said it was seven, or seven on each shoulder.

I never learned what became of Worley until reading American Exorcism, Michael Cuneo’s wide-ranging and rather sympathetic survey of people who occupy this shadowy corner of religious life. The late, “now largely forgotten” Worley plays quite a role in the book, as something of a trailblazer in bringing “deliverance ministry” into American Protestantism. Where mainstream preachers, such as my dad, generally regarded casting out demons as sensationalistic, backwoodsy, tent-revivalist stuff that belonged to a more primitive past, Worley began in late 1970 “performing exorcisms, wild, rambunctious affairs that sometimes raged on well past midnight.” And he did it all before The Exorcist hit the theaters – before, that is, the modern history of the subject really began.

As Cuneo charts it, William Peter Blatty’s novel and subsequent film hit something of a nerve in the American psyche; people “who might not otherwise have even considered the possibility that their problems were demonic in nature now had positive cultural incentive for doing so.” After the movie’s release, demon-spottings and demon-busting soared. Satanism, either in fact or in the popular imagination, took hold in America. In the paranoid culture of the 1980s, it figured into murder cases and rock lyrics, as well as one custody battle, “recovered memory” incident and daycare center case after the next.

Cuneo, who attended some 50 exorcisms in the course of his research, details the different ways this strange type of work is practiced across the Christian spectrum. Catholics, of course, have had a ritual for the expulsion off demons since 1614, but the church generally finds it an embarrassment and those who practice it, at least until recently, have tended to do so on the sly. For charismatic Christians – which include a variety of multi-denominational believers who embrace a “spirit-filled” life that includes speaking in tongues and faith-healing – possession and exorcism are all about “affliction” and “deliverance.” Here, the focus isn’t so much on demons who enter the body of a hapless lost soul as it is on waging war with the demons who torment the faithful. According to the people in the deliverance side of the house, demons may well be something you’re born with – they even talk of “transgenerational” evil that you inherit from your forebearers. There’s even one Christian psychotherapist in the book who employs something called a “genogram,” a genealogical tracking chart that helps determine where the demons first began to infect the family tree.

Groups differ as to the best way to cast out demons; for some it’s a sloppy public sideshow, for others a matter of prayer, devotion, and serious therapy. Do you let demons curse and scream, much as they did when they inhabited Linda Blair, or do you “bind them,” telling them to shut their blasphemous mouths in the name of the Lord? For some exorcists, all the shrieking, screaming, and puking are a vital part of the ceremony: “a certificate of authenticity, the surest, most visceral proof that demons – real spitting, jeering, profanity-addled demons – were actually being engaged in combat.” For others, letting Satan take the spotlight is just a drain on everyone’s time.

For people of a purely rationalist bent, all of this will likely seem quite mad, and people who see demons may not appear much different from people who see UFOs. But part of the reason for our lingering interest in both areas is that fairly serious people share the stage with outright kooks. How much of the truth is “out there,” and how much is the work of an overactive imagination?

Cuneo, not surprisingly, says that in all his time amidst the demons he never saw any head-spinning, levitation or fleshly graffiti, but he doesn’t dismiss exorcism out of hand either. In cases, it has a “placebo effect” for certain ills, regardless of whether demons were actually involved.

American Exorcism makes for an absorbing social history of a contemporary phenomenon, and our own continued fascination with the devil’s work.

Alibi (Albuquerque, New Mexico)

American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty, Michael W. Cuneo (Broadway Books ● Paperback ● $13.95)

By Steven Robert Allen

NEW OUT in paperback is a surprisingly open-minded look at a fun hobby that’s almost as popular now as it was back in the Middle Ages. No, I’m not talking about bloodletting or self-flagellation. I’m talking, of course, about exorcism. Cuneo goes several steps beyond mere anecdotal accounts of this widespread practice. He shows the relationship between these bizarre rituals and popular culture, exposing an aspect of modern American life that’s almost too freaky to believe.

The Tampa Tribune

Catholics Fear Implosion

The Smoke of Satan: Conservative and Traditionalist Dissent in Contemporary American Catholicism. By Michael W. Cuneo. Oxford University Press. 214 pages. $27.50

By Maggie Hall

THERE ARE POCKETS of the faithful who claim that the Roman Catholic Church went to hell in a handbasket after Vatican II, Pope John XXIII’s council to let fresh air into the sometimes-musty corners of the church.

The Tridentine Mass – now, there was spirituality, according to the anti-Vatican II set. Aging baby boomers remember Latin Masses intoned by a priest whose back was to the congregation.

Traditionalists eschew the folk Masses, Communion received in the hand and nuns without the wimples and heavy habits of long ago, all of which Vatican II brought in its wake.

Some dissenters are content to drive out of their way to attend Latin Masses, but others take their post-Vatican II opposition much more seriously. A diehard enclave in the Northwest has installed its own pope in opposition to John Paul II, whom they see as an agent of Satan.

In “The Smoke of Satan,” author Michael W. Cuneo distills conservative dissent in Catholic America into three groups, each of which attacks the changes from Vatican II in contradicting ways.

Catholic conservatives are moral militants who are still loyal to all of the Holy See’s teachings; they’re diehard in their anti-abortion stance and find commonality with other Christians in the Moral Majority.

That proximity to other Christians and their alliance to Rome horrify separatists, who might be called the lunatic fringe of Catholic dissent. Catholicism as it existed since St. Jerome was killed by Vatican II, they say. It’s up to them to purify the faith by dissociating themselves from things as they are. They form their own communities shut off from society; some ordain women and married men as priests.

Marianists, on the other hand, rely on visionaries – who are usually working-class women – to bring them dire warnings about the state of the world directly from Mary, the mother of Jesus. Their faith is grounded in the messages of the visionaries, who predict global destruction unless the world dedicates itself to Marian principles.

To the Catholic faithful, Mary is everywhere, even on the windows of a finance building in Clearwater.

The cult surrounding the late Veronica Lueken is Cuneo’s focus in the Marianist chapters. He interviews the still-faithful and the fallen away, who were mesmerized by the New York housewife’s conversations with Mary at Flushing Meadows, a park in the shadows of Shea Stadium in Queens. When Lueken drew groups to the grounds of her parish church, it took a denunciation from the pastor to drive them away. Lueken died in 1995, but her “Baysiders” continue to gather at Flushing Meadows to pray and discuss her transcribed messages.

If Lueken is the Marianist Madonna of dissent, then maverick priest Nicholas Gruner is the movement’s testy St. Paul. His Fatima Crusade group continues to press the pope to consecrate Russia to Mary, which the Vatican says it performed in 1942 and 1982.

According to Gruner’s flock, a consecration following the instructions communicated by Sister Lucia, the last surviving Fatima visionary, hasn’t been done to their satisfaction.

They claim that satanic elements in the Vatican are preventing this from happening, and the fate of the world is at stake.

One group decries conservatives who picket abortion clinics because they sing Protestant hymns, which they feel corrupts the Catholic faith. Another sect founder admits that his opposition to Rome puts him closer to traditional Protestant beliefs than to Catholicism.

Cuneo handles his interviews with great restraint, giving every point of view its voice. “Baysiders” who left the movement in disappointment over Lueken’s lifestyle and former members of the more radical sects balance the powerful personalities of the founders of the movements he profiles.

Cuneo’s treatment of a “jihad”-like Catholic underground that uses pamphlets in place of car bombs is not only enlightening but necessary. The average Catholic sitting in the pew on Sunday may not realize that Vatican II did more than change the language of the Mass.

Book Magazine

Michael W. Cuneo ● American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty (Doubleday, $24.95)

By Chris Barsanti

IF THERE WERE ever any question about the power of pop culture to influence people’s behavior and beliefs, it is put to rest by Michael Cuneo’s provocative and frightening book on exorcisms in modern-day America. Once an almost forgotten Roman Catholic rite, exorcism – the act of casting demons out of the supposedly possessed – was reintroduced into the popular imagination in part by the 1973 horror film The Exorcist and the hysterical 1976 bestseller Hostage to the Devil: The Possession and Exorcism of Five Americans. Since then, according to Cuneo, thousands of people have used demonic possession as a way to explain mysterious illnesses and mental problems, much to the chagrin of the church, which usually tries to distance itself from the practice.

Cuneo paints a broad portrait of an America where rogue Catholic priests and even Protestant (mostly Episcopalian and Pentecostal) ministers routinely perform exorcisms (called “deliverances” by non-Catholics). His research takes him to some fascinating places where ancient religious dogma meshes with New Age therapy. He’s so worried about not being judgmental, however, that he lets most of these self-styled spiritual warriors (the vast majority of whom seem little more than evangelical shysters) off the hook too easily.

Kirkus Reviews

Michael W. Cuneo ● The Smoke of Satan (Oxford)

A THOUGHTFUL, detailed exploration of three small but growing fundamentalist groups within post-Vatican II American Catholicism. The sweeping changes instituted by the Church in the 1960s were not greeted with equal enthusiasm by all American Catholics: A small but highly vocal minority felt the Church had impulsively abandoned its defining precepts. Cuneo (Catholics Against the Church) examines several distinct groups that have emerged from the “crisis of identity” caused by change: moral conservatives, including the militant late-20th-century crusaders against abortion; Catholic separatists, who have withdrawn from the Church and created their own isolationist communities; and Marianists, who seek guidance from the apocalyptic messages of the Blessed Virgin’s miraculous appearances.

Of these, the last two are perhaps the least understood. The conspiracy theories of separatists—who believe that John Paul II is a false pope, selected by communist forces intent on infiltration—are fodder for ridicule, but Cuneo never mocks his subjects. Rather, he seeks to understand separatism’s origins in the seeming vacuum of authority created by Vatican II, which liberalized the priesthood, granted power to the laity, and acknowledged nonpapal sources of truth. Similarly, the author places the Marianists in a context of the demythologization of Catholicism after the Council. Marianism explicitly rejects the deep-sixing of miracles, affirming a divine control of human history.

This is a winning ethnography of some unusual religious sects.

Catholic New Times

Cuneo presents balanced view of abortion issue

By Gerald J. Stortz

Michael W. Cuneo. Catholics Against the Church. University of Toronto Press

MICHAEL CUNEO teaches sociology at New York’s Fordham University. Previously, he co-authored (with Anthony J. Blasi) Issues in the Sociology of Religion.

Catholics against the Church is a rarity in the literature dealing with the abortion issue. The book is a finely tuned, academically sound, sociological study, and despite Cuneo’s protestations that it “is a historical investigation only in a quite secondary sense,” it is also a detailed chronicle of the anti-abortion movement in Toronto.

The book is noteworthy on two other grounds. Despite the fact that Cuneo lives and works in New York, he obviously has Toronto roots and understands the context about which he writes. The study is also balanced with representatives on both sides of the issue allowed to debate their case.

Cuneo has structured his work in a very traditional fashion, dealing with a brief history of the anti-abortion movement, the relationship between church hierarchy and movement, and a four-chapter analysis of anti-abortion protest.

In the early chapters, there are two things which stand out. The first is Cuneo’s reminder that, despite media characterizations of anti-abortion protesters as “Catholic,” the movement is not only multi-denominational but includes agnostics and atheists.

The second is the difficult position in which the Catholic hierarchy in general (and Cardinal Emmett Carter of Toronto in particular) finds itself. Although Cardinal Carter does not gain my sympathy on all issues, in this case he was in a no-win situation.

If he failed to speak out against abortion, the militant Catholic wing of the movement chastised him for lacking moral fiber. But whenever he did speak out, the liberal wing (which also included a good many Catholics) couldn’t help but cringe. In Canada’s pluralistic culture, the last thing they wanted was for the anti-abortion cause to be too closely identified with Catholicism.

This sometimes apparently schizophrenic relationship between protesters and church hierarchy consumes the rest of the book and renders it as important as it is.

Perhaps Michael Cuneo’s most valuable contribution comes in chapters 5 through 7. In “Varieties of Anti-Abortion Activism,” he takes pains to point out through biographical profiles that there is no typical pro-lifer; that activists come from a variety of educational, socio-economic and political backgrounds.

Particularly fascinating is Cuneo’s description of Catholic Revivalists, a group which equates a “soft” stance on abortion with the degeneration of the Canadian Catholic church, epitomized by the emphasis in recent years on social justice, which seems more concerned with mundane matters than with spiritual.

One must admire Michael Cuneo for writing a provocative, often disturbing work.

Daily Chronicle (De Kalb, Illinois)

Michael W. Cuneo ● American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty (Doubleday, $24.95)

‘American Exorcism’ a very interesting, compulsively readable book

By Chris Rickert

AUTHOR MICHAEL CUNEO’S driving thesis in the titillatingly titled “American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty” is simple enough.

Exorcism and its less ritualistic younger sibling, deliverance, are thriving in the technologically advanced, secularist culture of turn-of-the-century America, he says, thanks in large part to the popular media’s fascination with the subject and a malleable population eager for new-age healing and alternative therapies.

For Cuneo, William Peter Blatty’s 1971 novel “The Exorcist,” along with the 1973 movie of the same name, was key to the rebirth of this ancient practice. And in something of an ethnographic tour, he goes from coast to coast detailing all the different forms exorcism has taken over the past 30 years – from the formal exorcism performed by the Catholic priest, to mass deliverances in which entire roomfuls of people writhe and blaspheme and wrestle with lay ministers bent on forcibly evicting scores of demons.

That said, Cuneo takes great pains to leave the door open to the possibility that Satan is real, his minions are frequently cavorting among us and exorcisms really do work. The fact that he never reports seeing any credible evidence of any of this in the more than 50 exorcisms he attended might just mean he was continually at the wrong place at the wrong time.

What the reader is left with then is the age-old, logic-defying problem of faith. As a good academic, Cuneo cannot bring himself to abandon his well-honed objectivity, damn the relativistic posture of the modern university, and declare these people nutcases.

Which is fine. The argument that “just because you can’t see it, touch it, hear it or feel it, doesn’t mean it isn’t there” can become tedious – after all, anyone of us could simply be a brain in a jar, hooked up by some mad scientist to electrodes that merely make us think we eat, talk, live and breathe. But just as tedious is 300 pages of slamming an easy target.

“Some of the people I met during my research claimed to have experienced significant improvement in their personal lives as a result of undergoing exorcism,” Cuneo writes. “Their depression lifted, their fears fled, their inner torments dissipated.”

Wonderful. More power to them.

“American Exorcism” is a very interesting, compulsively readable look at a phenomenon that most people probably weren’t very aware of, questions about the existence of the Antichrist aside.

West Coast Review of Books

Michael W. Cuneo — American Exorcism (Doubleday, $24.95)

By B.W.F.

“IT’S ALL IN YOUR MIND!” would be a succinct summary of Michael Cuneo’s position on demonic possession. After attending fifty exorcisms, twenty of them the ones so sparingly performed by Roman Catholic priests, he has not yet seen any phenomenon that he can explain only by evoking supernatural powers. However, he is a professor of sociology and a skeptic – what the para-psychologists would call a goat – to delight Isaac Asimov and Randi: when every other witness sees the subject levitate, he sees nothing.

Although exorcism, in the strict sense, is a Roman Catholic ritual, the more charismatic Protestant faiths have a corresponding service called a deliverance. Cuneo reports that in some churches numerous believers experience deliverance simultaneously (but, correspondingly, the sufferers may require multiple treatments). However, there is obviously a temptation for persons to say, “The devil made me do it,” rather than admitting sin and undertaking penitence. And, as Cuneo notes, it is entirely possible for the minister to actually create the condition he, or she, is curing – vide the innumerable cases in which child abuse is remembered only after therapy is undertaken.

Cuneo finds it striking that demonic possession should have blossomed after the film The Exorcist and the novel Hostage to the Devil appeared (instead of the media only following behind the popular culture). But readers familiar with C.S. Lewis and his great classic The Screwtape Letters will see that this is reasonable indeed: the devil’s modern strategy of pretending not to exist allowed him to succeed in making so many conquests – but only until it was exposed. The philosopher Pascal pointed out that, because one cannot prove the non-existence of God, the safe wager is to behave as if He exists: correspondingly, the safe course is to assume that the devil can indeed possess souls.

Cuneo has a mastery of language that renders his work a pleasure to read, e.g., “American Catholicism probably has more bona fide exorcists at its disposal today than at any given time since the invention of color TV.”

While this book is no doubt intended for the general reader, there are ample references for anyone wishing to follow up the (gruesome) details.

The Christian CENTURY

Catholics Against the Church. By Michael W. Cuneo. University of Toronto Press, 288 pp., $40.00; paperback, $16.95

THIS BOOK is important both to readers in Canada, which is embroiled in a tense abortion debate, and in the U.S. Cuneo takes an almost absolutely noncommittal stand on the morality of abortion, and then applies social-scientific tools and good powers of observation to look at Canadian Catholicism.

No, opposition to abortion did not unite Canadian Catholics – anything but. Activists to the right make antiabortion the test of orthodoxy; those to the left insist on choice. Between them are church elites, including most bishops, priests and nuns, who “treat the issue with a circumspection bordering on avoidance.”

Cuneo’s findings show how Canadian Catholicism is in disarray, and how the abortion issue adds to the confusion. Indeed, it exposes the futility of hard-line and the precariousness of soft-line Catholicism as it resists or yields to modernity, pluralism, secularization and the like.

Neither Catholics nor people on either side of the abortion issue can take cheer from this study; it may alert other churches in Canada and in other nations. And it will shatter stereotypes.

America

Book Review: The Smoke of Satan by Michael W. Cuneo (Oxford)

By Martin R. Tripole

‘dissent (di sentﹶ ), v.i. 1. to differ in sentiment or opinion, esp. from the majority’

ꟷ Webster’s College Dictionary

MICHAEL W. CUNEO has given us a witty, even hilarious, and sometimes frightening study of the inner workings, the theological convictions and the major gripes of three different “factions” on the Catholic right: conservatives, separatists/traditionalists and apocalypticists and mystical Marianists.

I question whether it is fair to group the first with the last two (should one rank the reasonable alongside the eerie and kooky?) or to call them components of an “underground” church, when they all seem evidently above-ground. But Cuneo’s analysis of their views tries to be balanced. While he accepts the criticism that the post-Vatican II church has given us “an age of deadened ritual and flaccid theology” that spurs on the right, he also makes it clear he finds much of what the right supports to be lunacy.

What precisely is the cause of the religious right’s anguish? All of these factions are united in their rebellion against the equation of Catholicism and its countercultural values with the laissez-faire secular humanism of our liberated American society. Nearly a century after Pope Leo XIII’s condemnation of Isaac Hecker’s Americanism, Hecker’s brand of American Catholicism has come to dominate. And with it has come disintegration and disaster in just about every aspect of Catholic life.

There are significant distinctions among the three factions. For the conservatives, the aftermath of Vatican II has led to a crisis of morality, rooted in the widespread contraceptive mentality that rejects Humanae Vitae and makes abortion inevitable. There is also a crisis of theological identity. Theologians have traded a deposit of revelation rooted in the transcendent for the immanent possibilities of human life. And, most importantly, there is a crisis of authority; the intellectual elites now rule and personal conscience is master. The conciliar bishops have unwittingly catered to these crises due to their lack of spine. It is the task of the dedicated laity to restore the faith. The answer: Accept Vatican II and, by “public witness” against the inroads of abortion, keep genuine faith alive and rejuvenate the church.

The separatists are deeply divided among themselves, as schism after schism occurs, but conspiracy theories abound. False popes (e.g., John Paul II) have destroyed the church with heretical teaching, while the real pope is either imprisoned or the See of Peter is presently vacant. Some groups, such as the sizable Mount St. Michael community in Spokane, Wash., manifest certain Catholic militia tendencies toward the U.S. Government, which is viewed as trying to overthrow religion and establish a single world government. Their goal is to restore Christendom and the Tridentine Mass while advocating strict isolationism from a hierarchical church that is evil and irreformable.

Finally, there are the apocalypticists and mystical Marianists. The former propose three stages of chastisement and peace leading to a new Christendom ruled by Pope Gregory XVII, otherwise known as Father John Gregory of the Trinity, current head of the Apostles of Infinite Love. But this utopia will lead, unless their warnings are heeded, to a new period of chastisement and eventually to war and world destruction. There are also the Fatima Crusaders, whose goal is to publish the Third Secret of Fatima and have Russia consecrated to Mary – both with the approval of the bishops throughout the world. According to the Fatima Crusaders, Satan is still at work in the threat from Russian Communism, and unless the world repents, we are doomed. In addition, there is the movement of Veronica Luecken in Bayside, Long Island, where prayer vigils and messages from the Virgin Mary electrify countless thousands.

What is most amazing about the separatists and apocalypticists is the utterly bizarre nature of their forebodings of the end of time and the incredible depth of their convictions in strange, fantastic scenarios. Their leaders are scary individuals. In Veronica’s case, you either do what you are told or you are condemned to hell.

Cuneo has done his homework. His book is filled with direct data from personal interviews he conducted with the leaders of all the groups he analyzes (I counted at least 18). He makes us aware for the first time of the insidious nature of many of those seemingly innocent newsletters we receive from right-wing groups apparently in sympathy with the church. Sparkling with irony, he provides a clear picture of the deep divisions occurring in the right-wing of the church. At the same time, his reflections on their sinister operations leads to a disturbing question: How far will these divisions go, and when will they cease?

The Smoke of Satan is a cautionary tale containing an important lesson.

Skeptical Inquirer

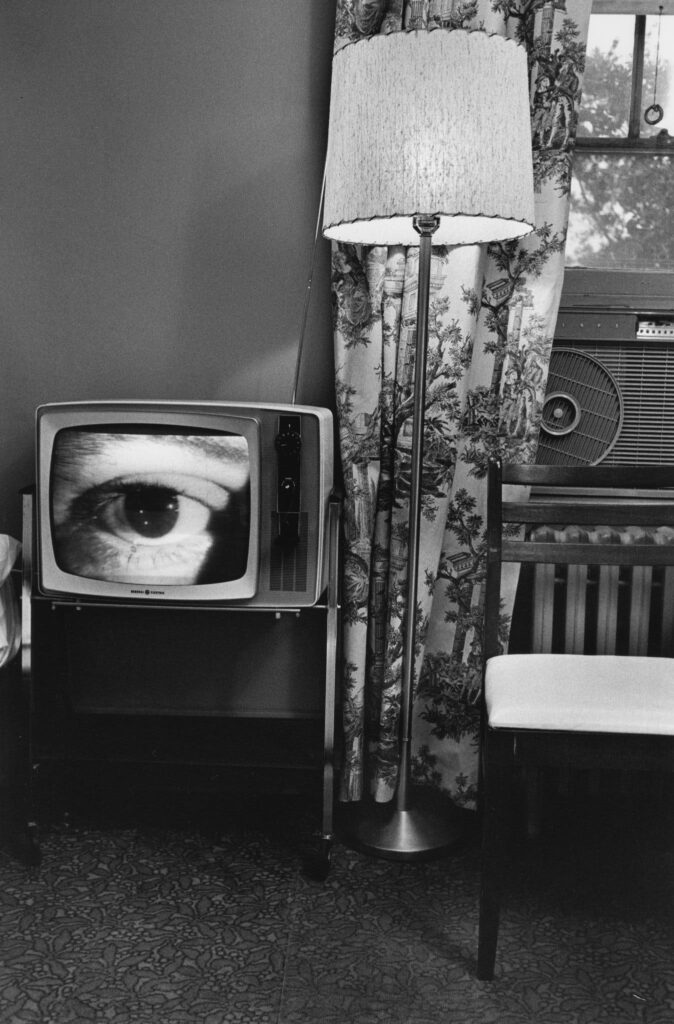

FOR SKEPTICS AND most other people, the word exorcism immediately evokes images of Catholic priests, holy water, and bizarre, other-worldly behavior. Most of the popular literature and media coverage focus exclusively on this Hollywood version of modern exorcism, a vicarious adventure into the dangerous side of religious experience. American Exorcism takes us beyond such cliché into the real believing subculture and the broader phenomena of demonology and ritual.

Author Michael Cuneo delves deeply into modern American beliefs in demon possession and the various practices of demon expulsion. Although his opening chapters focus mostly on exorcism as a Roman Catholic ritual, Cuneo is quick to disabuse readers of the common assumption that the task of expelling demons is limited to priests. His later chapters closely examine the history and current practice of Middle-America exorcism – the deliverance ministries of Baptist, charismatic, and Pentecostal churches and deliverance groups. Cuneo is also careful to make sure the reader understands that although Protestant deliverance ministry and the resurgent Catholic rite of exorcism are essentially grass-roots practices, the renewed popular belief can be credited almost entirely to Hollywood.

“This conjuncture of commercialism and religious ritual, of profits and piety, should come as no surprise,” Cuneo writes. “Over the course of the twentieth century the popular cultural industry, with its endless run of movies, books, and digital delights, has gained a pervasive influence over the national consciousness. It has become part of the very air that Americans breathe and, as such, it has attained an enormous capacity for shaping everyday beliefs and behaviors . . . When Hollywood and its allies put out the Word, somebody’s guaranteed to be listening.” Cuneo repeatedly reminds the reader of the role of American media in the resurgence of the belief in demonic possession. Only the most willfully naïve reader could overlook the role of motion pictures, TV talk shows, book publishers, and the insatiable appetite for publicity among exorcism authors and self-styled “researchers” after reading Cuneo’s perceptive accounts of the rise of demonic awareness in the land of plenty.

American Exorcism is a remarkable synthesis of interviews, historical research, media studies, and hands-on field research. Cuneo interviews the various players in the modern exorcism revival. He offers compelling assessments of desires and motives of the exorcists and the possessed – tempered by objective evidence and judgment. He shows forbearance and sympathy to those who participate in exorcism and deliverance ministry, but he is also skeptical and frank.

Cuneo begins his book with a poignant and timely lamentation of the modern Catholic priesthood: “The past three decades haven’t been particularly kind to the Catholic priesthood. One would be hard-pressed to find another profession that has fallen harder or further from grace in so short a period of time.” He notes the dramatic thinning of the ranks beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, the frantic scramble to find relevance in the modern world, and the endless sexual scandals. The image of the Catholic priest, writes Cuneo, “has more often been the priest as pious fraud, the priest as philanderer, the priest as yesterday’s man – equivocating, beleaguered, and thoroughly redundant.”

In one exceptional area, however, the priest remains a cultural hero. “That area,” writes Cuneo, “is exorcism, and it is the priest-as-exorcist that has somehow managed, in defiance of all odds, to retain a heroic grip on the popular American imagination.” Modern Catholic liberals had hoped that exorcism would be relegated to Church history along with other medieval trappings and customs. What such Catholics never anticipated, according to Cuneo, was the modern media’s role in breathing new life into the ancient rite of exorcism.

In the first four chapters, Cuneo deftly sketches out the sundry sources of the exorcism revival. He begins with the well-known pop Ursprung: William Peter Blatty’s 1971 novel, The Exorcist, and the 1973 film of the same title that it inspired. He characterizes Blatty’s work as a massive structure of fantasy resting on the flimsy foundation of a priest’s 1949 diary account of the possession of a young boy in Mount Ranier, Maryland.

Cuneo then introduces the reader to fascinating and seldom-cited sources: ex-Jesuit priest Malachi Martin, author of the 1976 book, Hostage to the Devil, paranormal authors Ed and Lorraine Warren, and, surprisingly, the grandfather of pop-psychology and self-help, The Road Less Traveled author M. Scott Peck.

Malachi Martin pronounced his final vows as a Jesuit in 1960 and took a position at the Vatican’s Pontifical Biblical Institute. He abruptly left his post in 1964 and the Society of Jesus in 1965, after being granted a provisional release by Pope Paul VI. Nearly fifty years later, there are conflicting accounts of why Martin, such a promising scholar, left everything behind. Cuneo writes:

“According to the most popular account (which is the one usually favored by Martin himself), he felt morally compelled to leave the priesthood over the new, decidedly more liberal direction the Catholic Church was taking as a result of the Second Vatican Council. Unfortunately, this stricken-soldier-of-conscience version of events hasn’t always squared with the facts. Far from being a tormented conservative during his years in Rome, Martin was actually a theological liberal, and while the council was in full swing, he was closely (and publicly) aligned with such leading liberal lights as Monsignor George Higgins and the eminent American Jesuit John Courtney Murray.”

Digging further, Cuneo finds “fairly reliable evidence” that Martin threw away his religious career in the wake of “romantic intrigue” – an affair that occurred in 1964 while he taught theology part-time at Loyola University of Chicago’s Rome Center.

If readers are to believe Martin, Satan was hard at work in New York City during the 1970s. He claims that the possessions and exorcisms described in Hostage are true accounts. Cuneo checks with Catholic experts, including Franciscan Father Benedict Groeschel, the expert Catholic officials turned to in the 1970s and 1980s when they were confronted with the “inexplicable.” Groeschel was not aware of anything on the scale Martin portrays. Furthermore, Groeschel and others insist that for the mainstream Catholic Church, exorcism was the last resort; earthly explanations were preferred and pursued first.

In his 1983 book, People of the Lie: The Hope for Healing Human Evil, Peck is unequivocal about his belief in demonic possession, and he remains a staunch believer in supernatural demonic possession to this day. Many in the charismatic deliverance movement see People of the Lie as a mainstream validation of their beliefs. When Cuneo asked Peck in a phone interview whether he thought that exorcism would someday become a serious subject of scientific investigation, Peck expresses doubt for absolutely shocking reasons. He is not pessimistic due to the fact that there is no credible evidence for the reality of demonic possession. Instead he asserts – in the tradition of a dime-a-dozen pseudoscientists rather than a trained psychiatrist – that the “country’s intellectual and religious elites” are to blame, including “the leaders of the American Catholic Church,” who “have seemed determined to keep the door shut.”

In Part III, “Charismatic Deliverance Ministry,” Cuneo sets Catholicism aside and begins with an account of a fifteen-minute exorcism of a young man named Paul. Paul, plagued by years of aberrant sexual fantasies and violent urges, had driven 200 miles to Kansas City to obtain an exorcism from Protestant deliverance ministers Ellen and Felix. The rite Cuneo describes is not an all-night vigil of sweating priests dodging projectile vomit. It involved a prayer, a recitation of Psalm 37 and Luke 10:17-19, some speaking in tongues, and a prayer of repentance followed by a prayer of exorcism appealing to the power of Jesus Christ, repeated six times for each demon within Paul. Cuneo remarks that the “whole business” was “orderly and efficient.” He also includes a postscript stating that six months later, Paul claimed that he had not experienced any of his old symptoms and “for the first time in his life felt truly at peace with himself.”

Cuneo then recounts the history of the rise of modern Pentecostal and charismatic deliverance ministry. Although it dates as far back as the very beginning of Pentecostalism in Los Angeles in 1906, the modern revival can be traced to the 1960s. At that time, deliverance ministry was a sporadic guerrilla movement, led by mavericks like Disciples of Christ minister Don Basham, Pentecostal minister Derek Prince, and, among charismatic Catholics, a Dominican priest named Francis MacNutt.

Cuneo’s historical account of deliverance ministry from the 1960s through the 1980s is filled with quotations from his interviews, providing an intense human portrait of what both leaders and followers in the movement felt and the role deliverance ministry played in their lives. Readers will also find a continuing interplay between Catholic and Protestant brands of exorcism. For instance, Malachi Martin’s pulp thriller, Hostage to the Devil, was a great influence on some of the modern Pentecostal deliverance ministers Cuneo spoke with, and many Catholics turned to Pentecostalism in their quest to infuse their faith with renewed fervor.

Cuneo spends time at Hegewisch Baptist Church in Indiana with Pastor Mike Theirer, “the hardest working exorcist in America.” His account stands in complete contrast to the more private and peaceful affair described above. Theirer’s deliverance sessions are auditorium affairs. “Throughout the auditorium, demoniacs are paired off with exorcism ministers,” writes Cuneo, who himself helped to wrestle down a particularly violent demoniac to prevent him from further battering Pastor Mike. People belched and (literally) vomited their demons out in an intense charismatic spectacle.

Cuneo’s close involvement with congregations practicing deliverance ministry gives him a compelling inside look and first-hand perspective on the conformist (sometimes cult-like) pressures exerted on members regarding belief and practice. Cuneo writes:

“Consider also the distinctive style of so many charismatic prayer groups: the ecstatic worship, the gushing emotionalism, the breathless solidarity. All of this gave rise, as often as not, to an atmosphere of suggestibility, of hothouse conformity. Individual charismatics, even relative newcomers, easily surmised what was expected of them in the way of belief and conduct, and there was no shortage of cues to help them along. Imagine a fairly new recruit to the renewal movement, impressionable, eager to please, seeing two or three, or fifteen or sixteen, spiritual brethren writhing and moaning in demon-induced torment. And then seeing the performance repeated time and again. It would take an iron act of will, arguably, for such a person not to go along for the ride.”

Cuneo describes how, at a symposium on deliverance, he himself was confronted by an overly zealous charismatic convinced that he was possessed. He also relates interview accounts of fascistic group leaders who quashed dissenters by attributing their complaints to demons of willfulness and condemning them to corrective exorcisms. He stresses, however, that such abuses are the exception rather than the rule.

Michael Cuneo’s conclusions on the actual existence of demons and the use of deliverance ministry and exorcism will almost certainly disappoint many Skeptical Inquirer readers who feel that the throat of patently unscientific nonsense should be slit wide open. Cuneo reserves judgment on many matters for which skeptics will see a clear verdict. After sitting in on fifty exorcisms, he is unequivocal about the fact that he saw nothing supernatural – certainly nothing out of The Exorcist or Malachi Martin’s salacious pulp-religion paperbacks. However, he remains equivocal about the possibility that demons exist. While his views on the efficacy of exorcism are tempered by documented tragedies of exorcists inadvertently killing their hapless subjects, Cuneo, who conducted follow-up interviews of people whose exorcisms he had observed, apparently accepts that exorcism might have therapeutic value.

Cuneo does emphasize one conclusion that all skeptics will gladly embrace. The Holy Army of priests, ministers, and laity who do battle with demons unquestionably takes its lead from the American mass media. Without Hollywood, ABC, or Malachi Martin’s publisher, the exorcism business would never have gotten off the ground. While Cuneo may in some cases be slow to condemn what is scientifically damnable, I believe that no skeptic’s library on occult or supernatural claims would be complete without American Exorcism. Cuneo has done quality research on all levels and from many angles. He opens the door for readers into a strange and amazing world, where people fervently believe that Satan and his minions are at work in a struggle that is simultaneously personal and cosmic. He also does an excellent job tracking the media’s role in popular belief, and he is refreshingly scathing in pointing out those who see religious beliefs as a means to pop fame.

The Catholic Register

Michael W. Cuneo. Catholics Against the Church (University of Toronto Press; $40 cloth, $16.95 paper)

By Suzanne R. Scorsone

[excerpted]

MICHAEL W. CUNEO is not only bright, thorough and systematic: the guy can write. The concluding chapter is perforce in sociologese. The rest of the book is in plain, vivid English. Whether or not you agree with all his analyses, you will find this book difficult to put down.

I am particularly struck by the objectivity, clarity and care with which Cuneo has laid out the perceptions and concerns of the various movement subgroups. He has his opinions, but allows the activists to speak for themselves. This is all the more admirable given the tendency of the wider society to stereotype all anti-abortionists.

Cuneo identifies three main categories of activists: civil rights, family heritage and Catholic revivalist.

●

For Catholic revivalists, according to Cuneo, anti-abortion activism is a venue for expression of dissatisfaction not only with contemporary society but with the post-conciliar Catholic Church.

“It seems to revivalists that the Catholic Church in North America has deserted the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob and converted to the Feuerbachian god, that projection onto the cosmos of humanity’s deepest aspirations and unrealized possibilities,” Cuneo writes. “In attempting to make faith relevant, progressives have debased it to a weepy sentimentality or, at best, a sociological hypothesis and, accordingly, have removed any compelling reason for becoming or, for that matter, remaining a Catholic” (p. 193).

As to Church structure, Cuneo writes, revivalists invoke a conspiracy theory. “Liberal theologians and diocesan bureaucrats, no longer themselves in possession of supernatural faith, have assumed the role of ‘second magisterium’ and are determined to convert the Church to the characteristic values and thought modes of secular humanism . . . This ‘revolt of middle management,’ according to revivalists, has brought into the open a confrontation of forces struggling for control of the Church” (p. 194).

The revivalists see themselves as a faithful remnant of laity, calling the Church to take a counter-cultural stand against the broader secular society.

Cuneo does overcome stereotypes. He makes it clear that revivalist Catholics are not anti-intellectuals defending their status against the enlightened. Their ranks are heavy with PhDs and professionals, along with white and blue-collar workers. The mothers of six tend to be university graduates who have chosen to remain at home with their children. Some revivalists are indeed nostalgic for the Latin Mass and the certainties of their youth, but most of these have acted on reflection. They are often under 30 and/or converts: they have chosen their piety.

The younger revivalist activists tend to be politically distant from the right. They trust neither capitalism nor communism: they see abortion-on-demand as symptomatic of the shallowness of the prevailing consumerist culture. Cuneo makes a point of saying that revivalist activists tend to be opposed to capital punishment, knocking yet another stereotype into a cocked hat.

●

So would I suggest that you read this book to better understand the anti-abortion movement in Canada?

Definitely.

This is good social science, very good social science. I wish there were more of it around.

Word Trade (Chapel Hill, North Carolina)

Michael W. Cuneo. THE SMOKE OF SATAN (Oxford)

AT THE SITE of the Vatican Pavilion at the old World’s Fair grounds in Queens, New York, where the late Veronica Lueken for years came to receive messages from the Blessed Virgin Mary, her followers still gather with apocalyptic expectancy before a portable statue of the Virgin. They are convinced that virtually the entire world, including the great majority of Catholics, will soon perish in a horrible chastisement, and that they alone will be saved.

In the theological underground of American Catholicism, mostly hidden from public view, the followers of Veronica are just a few among the many who regard both the broader society and the broader church as irredeemably corrupt.

Now, Michael Cuneo’s THE SMOKE OF SATAN brings these groups vividly to life, shedding valuable light on the current state of Catholicism in North America – and, more generally, on religion in our society.

Images on television and in the popular media have made the Christian right a household concept – but what that usually means is the Protestant Christian right. Cuneo’s insightful, provocative study highlights the equally vigorous though less well-known Catholic counterparts, ranging from the Marianists, such as the followers of “Blessed Veronica” of Bayside, to picketers at abortion clinics across the United States and Canada (militant lay Catholics who believe that “public witness” is a vocational enterprise of the highest order, one which the vast majority of bishops, priests, and nuns are too lacking in faith and nerve to perform themselves); from separatists who believe that even Rome itself has fallen and that true Catholics should withdraw and form alternate communities, to Latin Mass advocates who believe the reforms of Vatican II are the work of Satan himself.

These American Catholics are united by a common conviction: in the space of just several decades, the mainstream Catholic church in the United States and elsewhere has fallen into alarming decline, and the task of preserving authentic Catholicism (and thus Christianity itself) from outright extinction has fallen to small bands of the truly faithful. As Cuneo draws striking portraits of these faithful few, he also provides some fascinating asides on contemporary issues, including an innovative analysis of the ideological relationship of right-wing Catholic groups with the militia movement and a provocative assessment of militant Catholic prolife activism.

In 1972, speaking in the aftermath of Vatican II, Pope Paul VI said “the smoke of Satan has entered by some crack into the temple of God.” In this first full-scale account of Roman Catholic fundamentalism, Cuneo details what these disaffected Catholics believe the “smoke of Satan” to be, and what they plan to do to halt its spread.

Cuneo’s profiles of these right-wing groups and the various strategies they have adopted in attempting to carry out this task make for one of the most fascinating stories in contemporary American religion.

Religious Studies Review

Michael W. Cuneo. Catholics Against the Church (University of Toronto Press)

By Fred Maher

FASCINATING study.

Anti-abortion activism within the Catholic Church in Canada is interpreted as a struggle for the soul of the Church. “Revivalists” take to the streets to protest the perceived failure of the clergy to oppose, with real commitment, abortion and moral decay generally. Clerical lack of commitment is attributed to the priority the bishops place on ecumenism and on their alliance with “Social Justice” Catholics, who are more comfortable than the “Revivalists” with Vatican II, pluralism, and moral relativism.

Serious, insightful, and accessible. Anyone interested in the fault lines in the Catholic Church and/or the politics of abortion should read this volume.

Millennial Stew

Michael W. Cuneo: The Smoke of Satan (Oxford, 214 pages, with footnotes)

By G.B.S.

AN ILLUMINATING account of the schism which has occurred within contemporary American Catholicism since Vatican II, resulting in what the author has labeled as three distinct factions: Catholic Conservatives, Catholic Separatists and Catholic Marianists/Apocalypticists. Cuneo successfully presents the dominant themes which unite and, more often, divide these marginalized Catholics.

Though not dealing specifically with millennial issues, this book examines the unquestionably apocalyptic themes found within the Catholic Marianist/Virgin Mary phenomenon. Familiar apocalyptic Christian themes are echoed in the miraculous prophetic apparitions of the Virgin Mary, from La Salette, France, to Bayside, New York, including an imminent worldly cataclysm, the persecution of the true church, the evils of the modern (i.e., secular) world and the ever-present threat of communism.

It is interesting to note that many of the conspiracy theories and themes often trumpeted by conservative Christian Evangelicals such as the threat of a one-world religion and the controlling of international finance by a satanic elite called the Illuminati are also clearly present in the beliefs of these Catholic Apocalypticists. Unfortunately, so is the implicit and sometimes explicit anti-Semitism which so often accompanies such conspiratorial thinking.

Cuneo provides a fascinating glimpse not only into these movements and the attraction they hold for a growing number of Catholics, but also into the appeal that apocalyptic thinking can have for the marginalized and disenfranchised.

Choice

Michael W. Cuneo. Catholics Against the Church. University of Toronto Press. $40.00; paperback, $16.95

By D. Campbell

A READABLE, scholarly sociological and historical examination of the Canadian Catholic pro-life movement. Although its scope is intentionally narrower than Kristin Luker’s study of pro-choice and pro-life activists in Abortion and the Politics of Motherhood, Cuneo’s book is of much wider significance than its subtitle might initially suggest.

Both in his case studies of Canadian Catholic pro-lifers and in his treatment of “the politics of ecumenism” in the Canadian Catholic Church, Cuneo presents some provocative material that is of primary importance to those who wish to understand the recent history of the Roman Catholic Church.

Cuneo’s treatment of the Canadian bishops’ relationship with the pro-life movement underscores the not-so-subtle differences between the American and Canadian Catholic communities even as his penetrating portrait of contemporary “Catholic Revivalists” – a constituency sometimes called Catholic Traditionalists or Catholic Fundamentalists – illuminates a critical development in the recent history of the Catholic Church throughout the English-speaking world (and beyond).

Recommended for graduate and upper-division undergraduate students.

Good Reports

Michael W. Cuneo ● American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty

By Alex Good

WHEN WILDE WROTE that life imitates art, he was really only stating the obvious. Life, considered as the way we choose to live our lives, is an art. The things we make instruct us (for good or ill) how to go about it.

But we should be wary of extending his epigram too far. As an example of what can happen if we do, Michael Cuneo brings us this report (from the trenches, as it were) on exorcism in America.

Before 1971 exorcism, or the casting out of demons, was an obscure Catholic ritual that few people knew anything about. That all changed with the publication of William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist, a book that, by itself, gives its author a persuasive claim to being the most important Catholic novelist of the twentieth century. Its presentation of a pair of relevant (nay, heroic!) Catholic priests struck a chord with a church that was feeling under siege.

The notorious film version that came out two years later only further opened the gates of hell. Almost overnight a small cottage industry in exorcism sprouted up, even spreading to various Protestant denominations (though it has been hard for the Holy Rollers and other groups to match the spiritual cachet of the full Catholic ritual). Cuneo’s explanation for why this happened is commendably clear. In the first place he blames the media: Blatty and his spawn. The exorcisms Cuneo attends play out like amateur versions of scenes from The Exorcist and other movies, albeit without any of the special effects. It seems nothing is sacred from Wilde’s mimesis in reverse:

“Am I really suggesting,” Cuneo writes, “that the popular entertainment industry, with all its dreck and drivel, is capable of manipulating – actually manipulating – religious beliefs and behavior? Indeed, this is one of the main contentions of the present study, and there seems nothing (to my mind) especially far-fetched about it. Like it or not, the products of Hollywood and the tabloid media are an inescapable fact of life in contemporary America . . . they play a crucial role in shaping public sentiment and engaging the national psyche. Why should religiously inclined Americans be less susceptible to their charms than anyone else? When Hollywood or Oprah or Madison Avenue advertises the existence of demons and satanic cults, it is hardly surprising that at least some Americans will comport themselves accordingly.”

The second contributing factor has been the “therapeutic ethos of the prevailing culture.” The notion that one’s drunkenness and lust are the result of demonic infestation rather than personal weakness suits us well:

“No less than any of the countless New Age nostrums or twelve-step recovery routines on the current scene,” Cuneo writes, “exorcism ministries offer their clients endless possibilities for personal transformation – the prospect of a thousand rebirths. With its promises of therapeutic well-being and rapid-fire emotional gratification, exorcism is oddly at home in the shopping-mall culture, the purchase-of-happiness culture, of turn-of-the-century America.”

curledup.com

Almost Midnight. Michael W. Cuneo. Broadway Books. Hardcover. 352 pages

By Barbara Bamberger Scott

DARRELL MEASE is in prison for life, but not forever. God is his lawyer, and he figures the Almighty will spring him one of these days, for sure. After all, he was saved from execution by the Pope and he’s not even Catholic. With a miracle like that on your rap sheet, the sky’s the limit.

Not bad for a guy who murdered three people – man, woman and crippled teenager – in a cold-blooded vicious manner that certainly begged the death penalty, according to a jury of his peers. But Darrell is a man with few peers.

Michael W Cuneo, author and professor, has gone as deep into the life and ethos of Darrell Mease as anyone should dare. He has a respectful relationship with the murderer, and he wants the world to understand Darrell as well as he does.

Mease grew up in the hard-scrabble Ozarks, before Branson brought a modicum of respectability to what had always been seen as a hillbilly enclave, where local heroes were likely to be legendary bank robbers or mountain men with long knives. Darrell is a kind of local hero. Brought up Pentecostal, he is still adored by his mother, Lexie, who sees him as God’s instrument and who has spent hours on her knees praying for him. As a boy, Darrell was likeable and not much of a scholar, though he had smarts. He just loved to hunt and roam the woods, and he learned from his Daddy how to shoot and kill innocent critters.

Vietnam moved him up a gear in the killing game. He came back haunted by survivor’s guilt, though no one’s trying to make too much of that. Darrell had chances, like we all do, and he made a mess of two marriages and all attempts at gainful employment. He wasn’t lazy, and he had his pride. But he blew a lot of good opportunities and wound up in a nasty vendetta scenario with a man named Lloyd.

Lloyd was a mixed bag, like Darrell. He dealt hard drugs, and those who hated him were as many as those who thought him a pretty nice fellow. He’d play Darrell along, promising him things and not delivering, and finally put a hit out on Darrell, who, it must be said, was hoping to share Lloyd’s limelight as a bigtime drug empresario.

Darrell and the love of his life, Mary, left the Ozarks and traveled in a big crazy circle out West and back. Mary wanted to settle down, but Darrell was obsessed with the paranoid notion that Lloyd would somehow track him down. The only solution was to hit before he got hit. In the commission of this crime, he just had to knock off Lloyd’s wife and his paraplegic grandson, who happened to be at the scene.

Darrell and Mary took off again, Bonnie and Clyde-like, living the outlaw life out West. They held hands and looked at sunsets, and fought hunger and despair while she worked as a waitress. When finally apprehended, they were sleeping in their car, their last possession of any value. Not exactly an enviable finish to a grubby, violent story.

Darrell had a conversion while awaiting trial. Even those who were meeting him for the first time commented on his placid demeanor. But he was convicted and slated for lethal injection, and that seemed to be that. A date was set.

On January 27, Darrell’s death date, the Pope was going to visit Missouri, so the execution was postponed. It was well known that the Pope disapproved of capital punishment and wouldn’t like a man being executed on his watch. Who’d have thought it? The Pope personally asked the Governor of the state, Mel Carnahan (who was killed shortly thereafter in a plane crash), to “have mercy on Mr. Mease.” The Pope felt it would be unfair to stay Mease’s death for a few weeks just because of his visit, and then snuff him once his temporary savior was back in the Vatican.

On such a feeble thread Darrell’s life appended, and on Carnahan’s decision he was granted a permanent stay, in prison, with no chance of parole.

But Darrell, and his mom, believe he’ll walk free one day. That would make one hell of a sequel.

The Canadian Catholic Review

The Revivalist Vision of the Church

By Keith Cassidy

Michael W. Cuneo. Catholics Against the Church (University of Toronto Press; soft cover, $16.95)

[excerpted]

ANYONE SERIOUSLY interested in the current state of the Catholic Church in Canada or in the abortion controversy must read this book. Not that this necessarily implies that all will agree with its contents – far from it – but the author has asked important questions, pursued his inquiries vigorously, and has presented his conclusions with considerable verve and intelligence.

This work is so rich and suggestive that a short summary of its argument is necessarily unsatisfactory. In essence, however, Cuneo maintains that the abortion controversy, rather than being a bond of unity among Catholics, is a source and symbol of bitter divisions.

Those Catholics (referred to by Cuneo as “Revivalists”) for whom abortion is a momentous issue on which there can be no compromise have found themselves frustrated and appalled by what they perceive as the timidity, accommodationism, and failed spiritual commitment of much of the hierarchy and its apparat. These have reciprocated with hostility or disdain.

Cuneo suggests that “Revivalist Catholicism” is based on the twin convictions that North American culture has lapsed into moral anarchy, which has been absorbed by the institutional Church, and that the authentic Church is “an enclave of stalwart believers” who are faithful to Catholicism’s unchanging teachings and “at war with the neo-paganism of society.”

More provocatively, Cuneo argues that the anti-abortion activism of Revivalist Catholics “is incompletely understood without an appreciation of its symbolic meaning.” In other words, even when their style of protest is counter-productive, it is a means of “producing and consolidating a contracultural religious identity.”

●