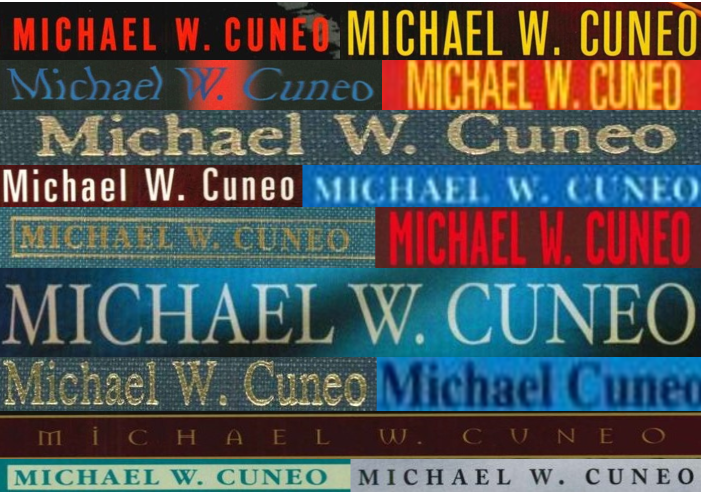

Contents

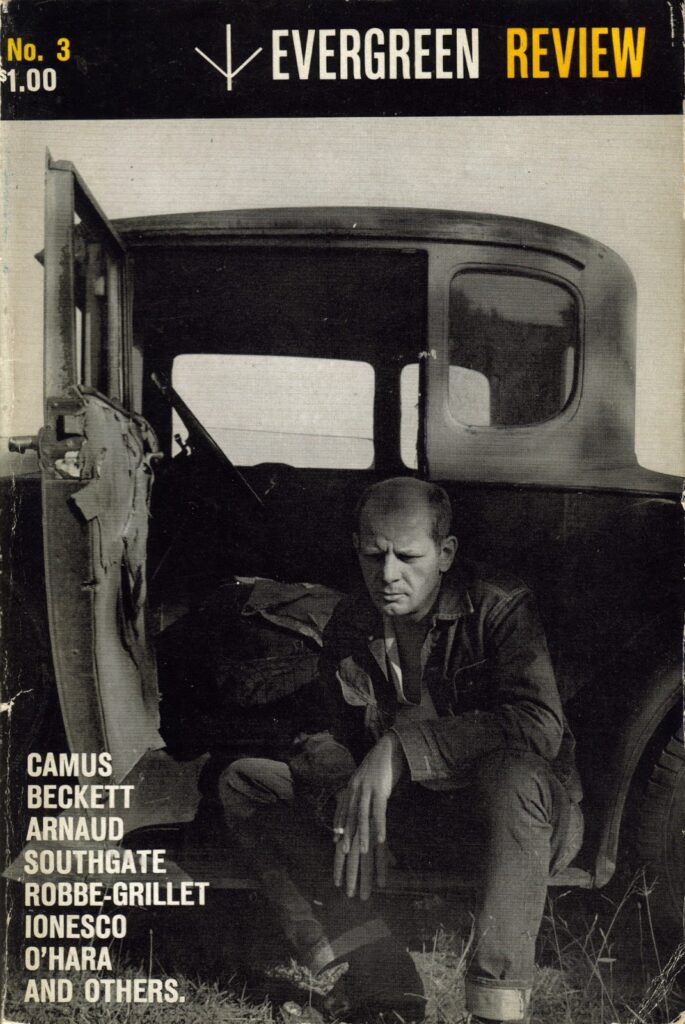

The New Yorker — The Devil Inside

Tallahassee Democrat — John Hawkes Nails the Role of His Career

The New York Times Magazine — Is the Pope Catholic . . . Enough?

The New York Times — Shoring Up Satan, Closing Limbo

The New York Times — Exorcists and Exorcisms Proliferate Across U.S.

The New York Times — Vatican’s Revised Exorcism Rite Affirms Existence of Devil

The New York Times — Pope’s Appeal Not Enough to Bridge Divide on Executions and Other Issues

The New York Times — Abortion Clinic Violence Stirs Debate Among Church Leaders

New York Magazine — Winter’s Bone’s John Hawkes on His Oscar Nomination

Daily News (New York City) — Exorcism, Made Easy

Daily News (New York City) — Satan and the Saint

Daily News (New York City) — Tuesday in New York

New York Newsday — In Sad Times for Church, the Spies Have It

Los Angeles Times — Exorcism Flourishing Once Again

The Philadelphia Inquirer — Deliverance Ministry Keeps Him Busy

Austin American-Statesman — Exorcisms Aren’t Rare, Writer Says

Arizona Republic (Phoenix) — Big Books

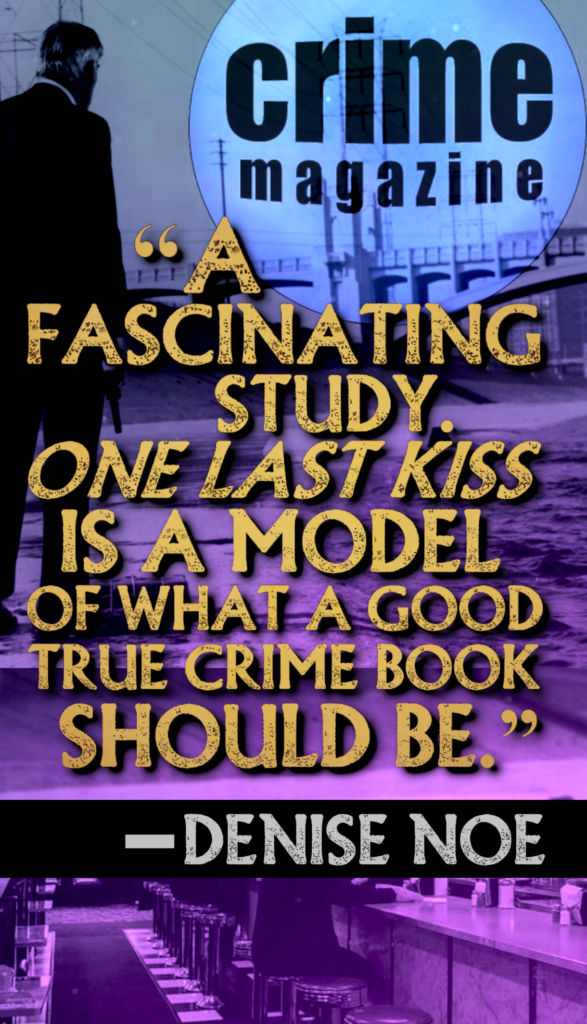

Publishers Weekly — The Year in Books

St. Louis Magazine — A Family Erased: The Chris Coleman Story

Daily Press (Newport News, VA) — Outcast Catholics Reject Reforms

ABC News — Exorcism Thriving in U.S.

The Spokesman-Review (Spokane) — The Good Fight

Tulsa World — Catholic Priest is Trained Exorcist, Calls for his Services are Increasing

Fort Worth Star-Telegram — Casting Out Demons

Fort Worth Star-Telegram — Interest in Exorcism Surges Due to Film’s Re-Release

The Charlotte Observer — ‘Duking it out with Demons’

Edmonton Journal — Sunday Pick

The Wichita Eagle — A Look at Devilish Developments

The Boston Globe — Atheists Claim Freedom From Religion

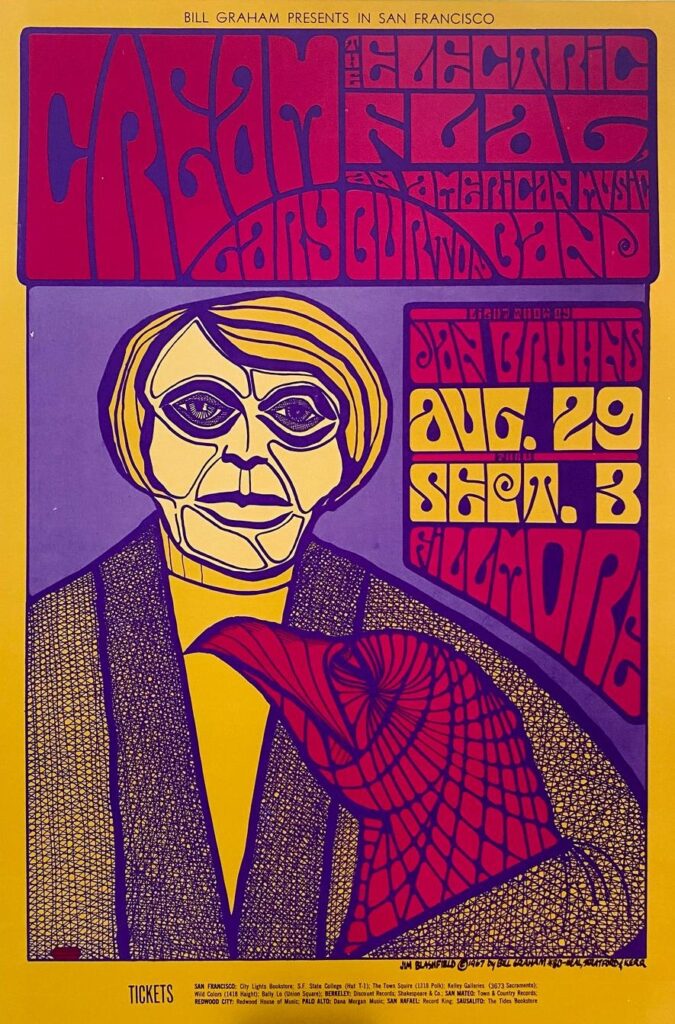

SF Weekly (San Francisco) — Return of the Devil: Exorcism’s Comeback in the Catholic Church

The Cincinnati Post — Demon Buster

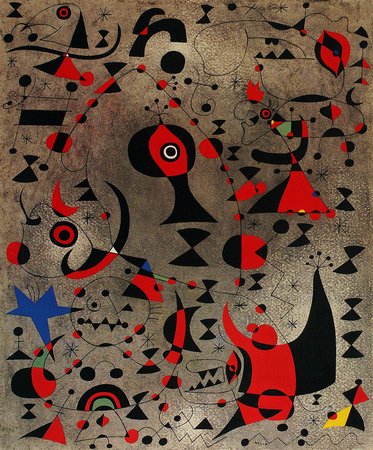

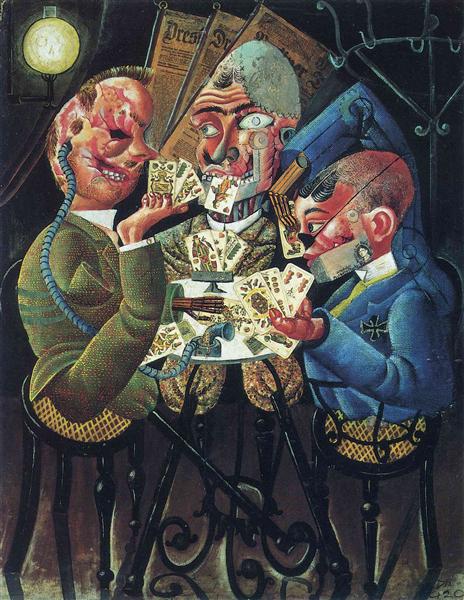

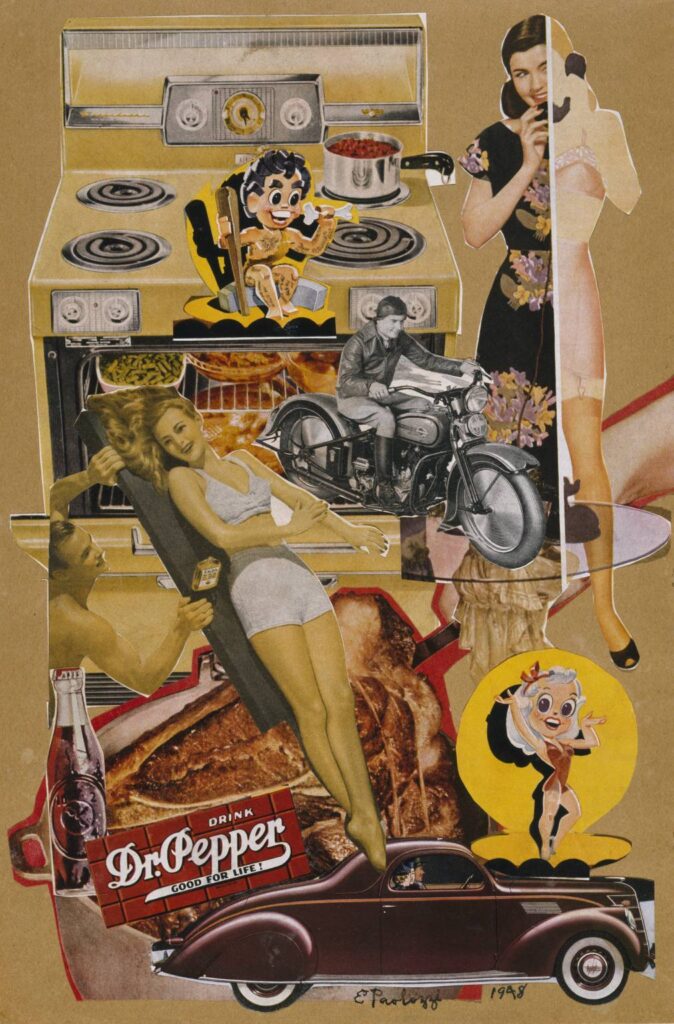

Contexts — The Devil’s Playthings

Newhouse News Service — Both Sides Trying to Eliminate Violence from Abortion Dispute

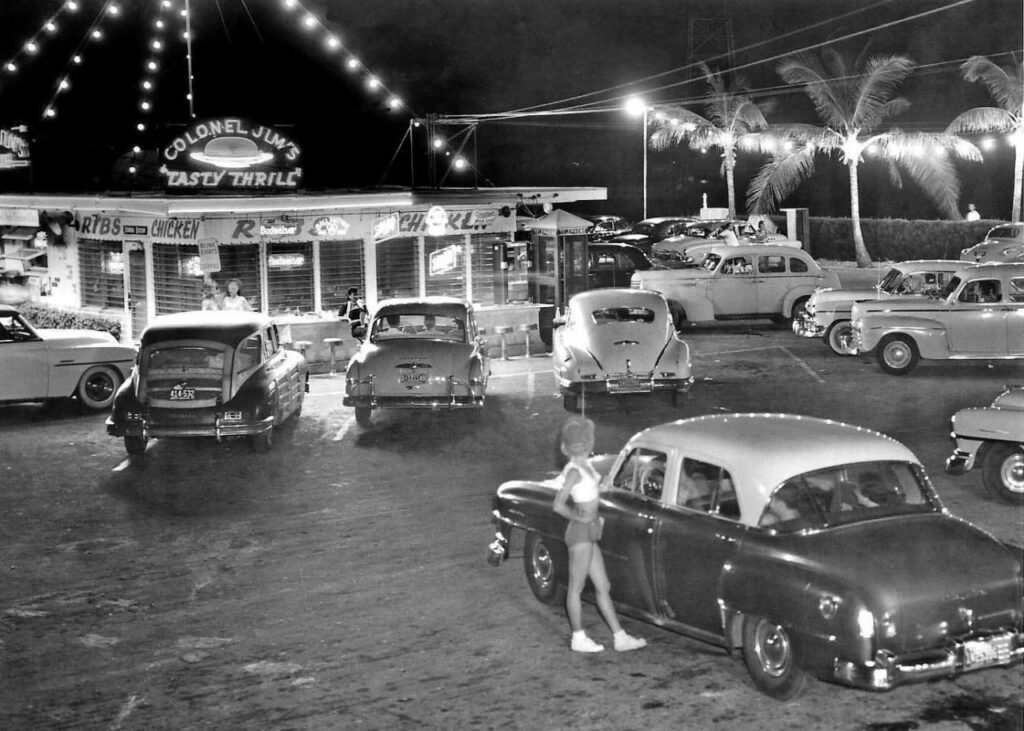

Miami Herald — Some Catholics Hold Fast to Tradition

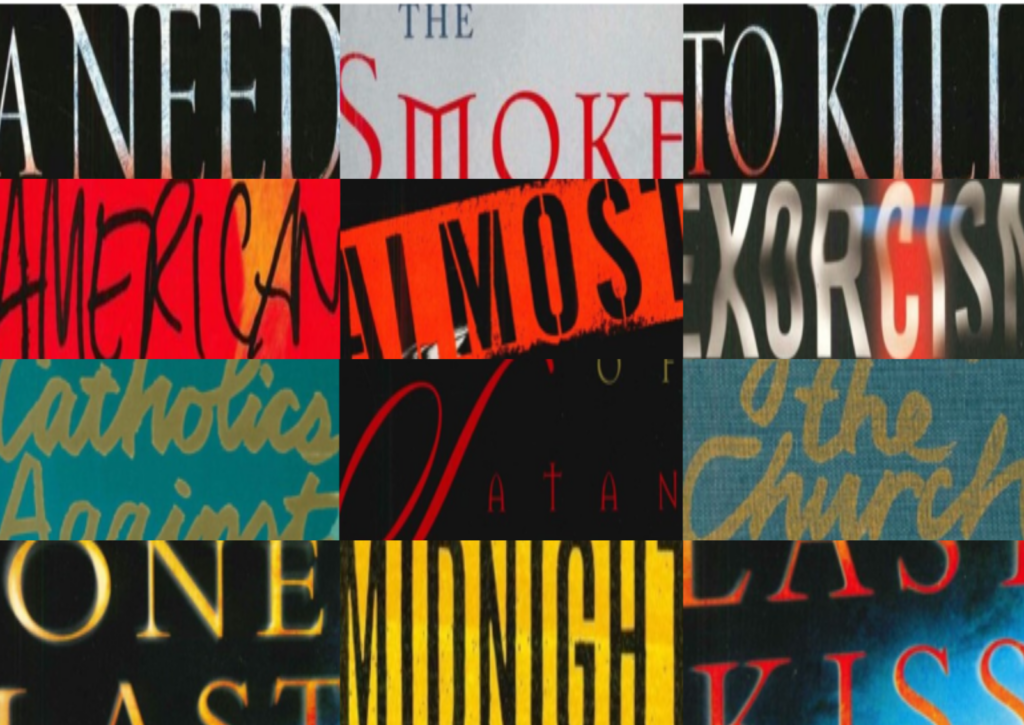

Daily Chronicle (De Kalb, IL) — ‘American Exorcism’ an Interesting, Compulsively Readable Book

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution — Delusions and Demons

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution — Books Preview

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution — The Abortion War

The Record (North Jersey) — How to Protect Yourself from Evil Spirits

Panama City News Herald (Florida) — Influence and Inspiration

The Post-Standard (Syracuse, NY) — Woman’s Mary Message Questioned

Christianity Today — Possessed or Obsessed?

Herald Statesman (Yonkers, NY) — Legionaries of Christ Boost Profile in Area

Insight on the News (The Washington Times) — ARE THEY DEMONS OR JUST DELUSIONS?

Calgary Herald — ‘Driving Out Demons’ Has Often Led to Death

Our Town (New York City) — More Catholic than the Pope

The Hamilton Spectator — Dealing with the Devil

The Washington Post — Campaign of Violence Against Abortion Clinics

The Washington Post — Clergy Group to Commemorate History of Support for Abortion’s Legalization

Reason — Jewish Demonic Possession Returns

The Seattle Times — Demons Usually in the Mind Not the Body, Experts Say

Newsweek — What is Exorcism?

The Catholic Telegraph (Cincinnati) — U.S. Catholicism Focus of Theology Program

The Frederick News-Post (Maryland) — Sociologist Gives Lecture on Death Row Inmate

Gettysburg Times (Pennsylvania) — Arts & Leisure Calendar

Religion in the News — Puffing Exorcism?

Lincoln Journal Star — Fundamentalism in Catholic Church

Intelligencer Journal (Lancaster, PA) — Haines Case to be Featured on ID Show

St. Joseph News-Press (Missouri) — Exorcism Explained

The Oklahoman (Oklahoma City) — Tulsa ‘God’s E.R.’ Sessions Cast Out Demons

The Vancouver Sun — Unholy War

The Salt Lake Tribune — News of the Weird

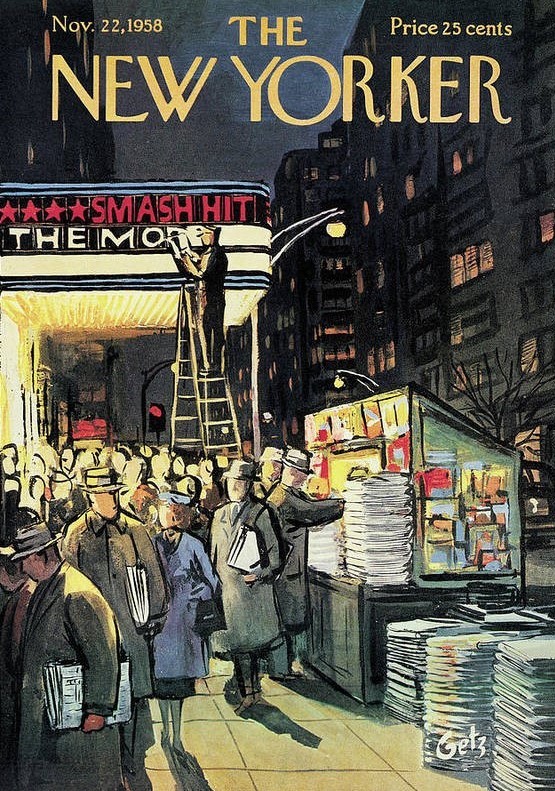

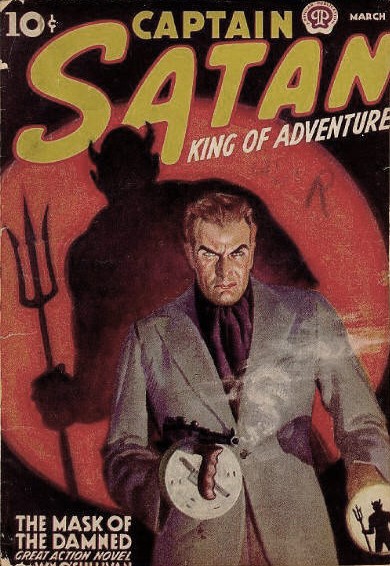

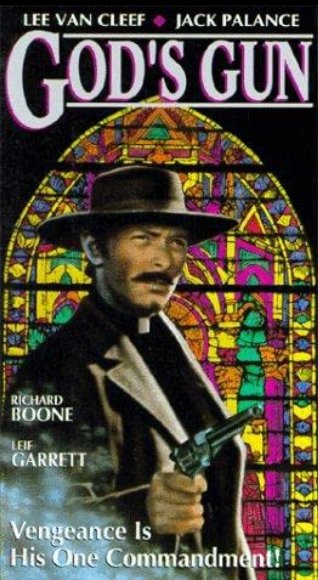

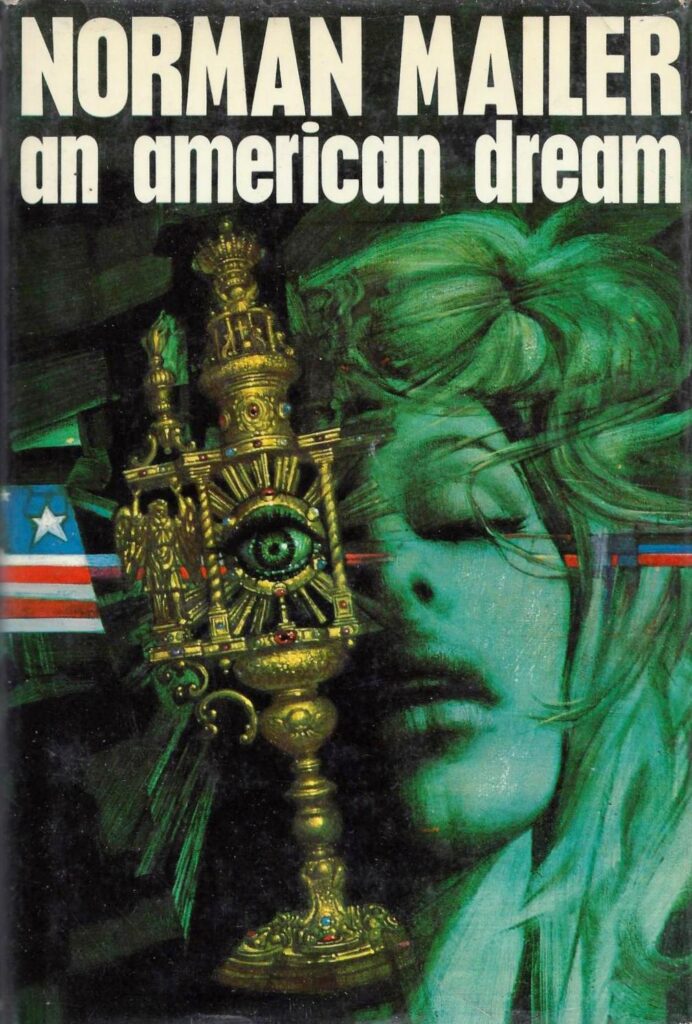

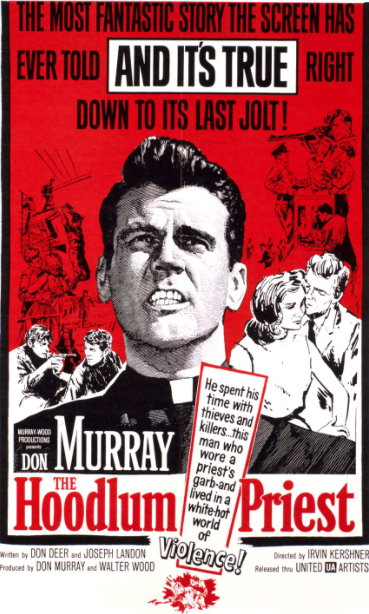

The New Yorker

The Devil Inside

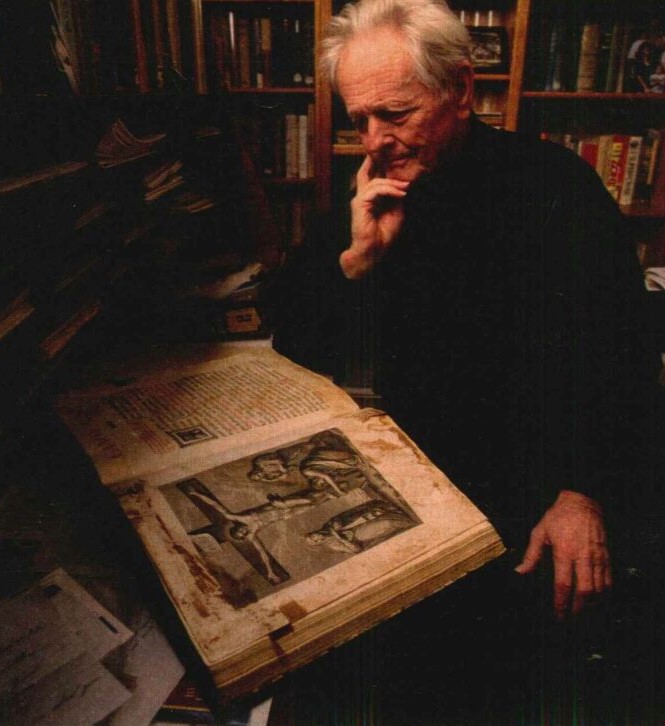

By Mark Rozzo

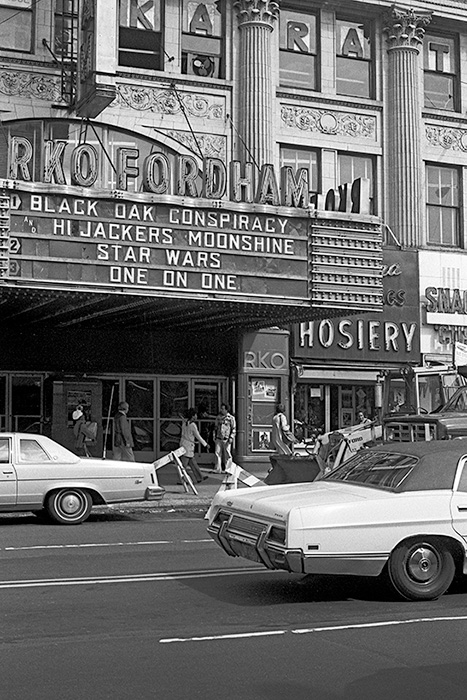

IN THE YEARS since William Friedkin’s 1973 horror extravaganza, “The Exorcist” – which was rereleased with considerable fanfare last year – the archaic rite of casting out demons has become more popular than ever. So argues the Fordham professor Michael Cuneo in his AMERICAN EXORCISM (Doubleday), a recently published history of the contemporary resurgence of exorcism and belief in demonic possession. Cuneo sat in on dozens of exorcisms, finding that these days the controversial procedure (typically scorned by Catholic officials) runs the gamut from Linda Blair-style “puke-and-rebuke sessions” to mellow suburban affairs attended by hot chocolate, cookies, and potato chips.

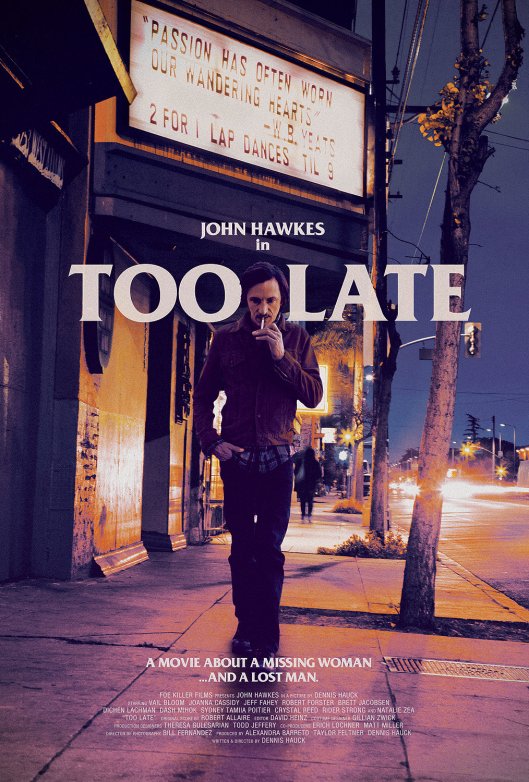

Tallahassee Democrat (Florida)

John Hawkes Nails the Role of His Career

By Mark Hinson

[excerpted]

ACTOR JOHN HAWKES is getting plenty of Oscar buzz for his riveting portrayal of the flinty, intimidating uncle Teardrop in the drama “Winter’s Bone.” The indie film took top prize at this year’s Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

Besides delving into the novel “Winter’s Bone” by Daniel Woodrell, Hawkes also researched the role of Teardrop by reading the real-crime book “Almost Midnight: An American Story of Murder and Redemption” by Michael W. Cuneo.

“‘Almost Midnight’ is all about the meth belt in the Ozarks,” Hawkes said. “It really goes into their clannish ways and their ‘honor among thieves’ beliefs. When I got to Southwest Missouri (to shoot ‘Winter’s Bone’), I sought out the same places I’d read about in Michael Cuneo’s book. They’re the places everyone in Branson told us not to go. So I went. I’d sit at the bar just to see how well I fit in.”

Judging by the Teardrop who appears on the big screen, he fit in frighteningly well.

The New York Times Magazine

Is the Pope Catholic . . . Enough?

By Christopher Noxon

[excerpted]

THE FACT that Mel Gibson is building a church in the hills near Los Angeles should come as no huge surprise. Gibson’s Catholicism has never been a secret, and in fact gives him a sort of reverse-exoticism in a town where other stars dabble in Buddhism, kabala and Scientology. An avowed family man still on his first marriage, with seven children to show for it, Gibson smokes, raises cattle, publicly shuns plastic surgery and seems wholly unmoved by most of the liberal-left causes favored by industry peers. Recently, however, something beyond the impulse to entertain has been showing up in Gibson’s work. Last year he played a former minister who rediscovers religion amid an alien invasion in “Signs” and a reverent Catholic lieutenant colonel in the war drama “We Were Soldiers.” In these films, but especially in a new movie, a monumentally risky project called “The Passion,” which he co-wrote and is currently directing in and around Rome, Gibson appears increasingly driven to express a theology only hinted at in his previous work. That theology is a strain of Catholicism rooted in the dictates of a 16th-century papal council and nurtured by a splinter group of conspiracy-minded Catholics, mystics, monarchists and disaffected conservatives – including a seminary dropout and rabble-rousing theologist who also happens to be Mel Gibson’s father.

Gibson is the star practitioner of this movement, which is known as Catholic traditionalism. Seeking to maintain the faith as it was understood before the landmark Second Vatican Council of 1962-1965, traditionalists view modern reforms as the work of either foolish liberals or hellbent heretics. They generally operate outside the authority or oversight of the official church, often maintaining their own chapels, schools, seminaries and clerical orders. Central to the movement is the Tridentine Mass, the Latin rite that was codified by the Council of Trent in the 16th century and remained in place until the Second Vatican Council deemed that Mass should be held in the popular language of each country. Latin, however, is just the beginning – traditionalists refrain from eating meat on Fridays, and traditionalist women wear headdresses in church. The movement seeks to revive an orthodoxy uncorrupted by the theological and social changes of the last 300 years or so.

Michael W. Cuneo, a sociology professor at Fordham University who reported on right-wing Catholic dissent in his book, “The Smoke of Satan,” wrote that traditionalists “would like nothing more than to be transported back to Louis XIV’s France or Franco’s Spain, where Catholicism enjoyed an unrivaled presidency over cultural life and other religions existed entirely at its beneficence.”

The New York Times

Shoring Up Satan, Closing Limbo

By John Tagliabue

ROME, Jan. 31 – IT SEEMED LIKE a season for traditionalists.

First came the Vatican declaration last November that in celebration of the third millennium of Christianity believers will be offered a wider array of indulgences, ways to earn amnesties from various forms of punishment in the afterlife.

Then there was the announcement just before Christmas that Padre Pio, the celebrated Italian mystic and healer who is a hero of traditionalist Catholics, would be beatified this May, the final step before canonization. (Pope John Paul II has made 270 saints, more than any other pope in history, and has beatified almost 800 people.)

And last week the Vatican published a revised Catholic rite for exorcism, the ancient ritual for expelling demons, reaffirming for doubters that the Devil does indeed exist and is very much at work in the world.

More is coming. Later this year the Vatican will publish an updated martyrology, the list of the 10,000 or so recognized saints and martyrs.

All these practices are subjects of debate among Catholics and between Protestants and Catholics. Since the Second Vatican Council, which concluded in 1965, the church has sought to shift emphasis from some of them. Liberal Catholics are uneasy about religious customs that appear to reflect older, legalistic approaches to achieving salvation. The Protestant Reformation disdained the cult of saints, and many Catholics are uncomfortable with the idea of indulgences, which appear to offer a shortcut to heaven. Most of all, though, talk of driving out demons evokes for many images of “Rosemary’s Baby” and “The Exorcist” rather than profound spiritual values.

As the papacy of 78-year-old John Paul II enters its third decade, the Vatican appears to be pursuing divergent goals. The mandate of the Second Vatican Council to bring the church up to date has been taken seriously. But at the same time, John Paul clearly rejects wholesale change. He clings, for example, to the notion of priestly celibacy just as firmly as he bans even discussion of the ordination of women.

Yet the Vatican, under his aegis, continuously enacts lesser changes designed to make ancient customs compatible with the spirit of the times. The Vatican struggles, experts say, to take into account the sensibilities of a widely varying membership in broadly differing societies.

In recent decades, Catholics have faced wrenching changes, large and small. “Whatever happened to Limbo?” older Catholics may ask. The church once taught that it was the place where unbaptized infants went when they died. It’s still around, goes the new thinking, but it’s empty. It is now believed to have been the state of natural bliss enjoyed by the just, like Abraham and Moses, who died before the Ascension of Christ to heaven. The Ascension brought them to heaven as well, and the babies got there too.

Many familiar symbols of devotion, like the scapular, once worn around the necks of millions of schoolchildren, are much less common now. Pieces of wool encased in plastic with iconic pictures, scapulars were believed to confer spiritual benefits much like indulgences. Some varieties were supposed to ensure salvation if a person died wearing it.

But exorcism, rather than fading away, has seen a revival among a segment of Catholics. Though ancient and widespread, the practice of exorcism and belief in demons are, for many Catholics, more science fiction than reasoned spirituality. The vast majority of Catholic theologians, said Michael W. Cuneo, a Fordham University sociologist, regard exorcism as “utter foolishness.” The Vatican itself, in proposing the revised rite, took pains to draw Christians away from notions like those spread in popular literature and films like “The Exorcist,” while at the same time holding firm to belief in devils.

Partly, the Vatican’s reaffirmation of the Devil and exorcism may be designed for the church in developing countries, where belief in spirits is widespread.

Yet even in countries that view themselves as sophisticated, like the United States, there is a flourishing market for exorcism. “People are looking to be delivered of demons of alcoholism, demons of marital infidelity, demons of depression,” Mr. Cuneo said, “and exorcism winds up the quick-fix solution.”

Six years ago, Mr. Cuneo said, there was one official exorcist in the American Catholic church; now there are 10. In addition to official exorcisms, many such rites are performed clandestinely, he said, often by priests “with traditionalist leanings.” And the renegade exorcists are every bit as vexing to the Vatican as are attacks on belief in spirits.

Last week the Vatican again urged bishops and priests not to confuse psychological suffering and possession, and to seek medical help while at the same time offering spiritual consolation. “You rule out the possibility of an organic problem, of hysteria,” Mr. Cuneo said, “and this is consistent with a long line of Vatican thinking.”

The New York Times

Exorcists and Exorcisms Proliferate Across U.S.

By John W. Fountain

CHICAGO, Nov. 24 – THERE ARE DEMONS HERE, some people say, the kind that torment and manifest themselves with spit-spewing and violent convulsions through the people they possess, evil spirits that can trap people inside themselves and utter foreign languages.

That belief was at the root of a decision by the archdiocese of Chicago to appoint a full-time exorcist last year for the first time in its 160-year history. It is the same reason that the Rev. Bob Larson, an evangelical preacher and author who runs an exorcism ministry in Denver will hold one of his “Spiritual Freedom” conferences in the ballroom of a suburban Chicago hotel in January.

Mr. Larson, who said he had 40 “exorcism teams” across the country, hopes to assemble a similar team here in Chicago to perform the ancient ritual for those believed to be possessed by the Devil.

“Our goal is that no one should ever be more than a day’s drive from a city where you can find an exorcist,” said Mr. Larson, who says Christians have the authority by Jesus Christ to drive Satan out of the possessed. “Why should that freak us out?” he said. “It’s in the Bible. Christ taught it.”

The number of exorcists and exorcisms has increased across the country in the last 10 years, experts said. While Chicago’s archdiocese has one official exorcist, New York City’s diocese has four, including the Rev. James J. LeBar, its chief exorcist. The Chicago archdiocese has not disclosed the identity of its exorcist, largely to maintain the privacy of those seeking his services, church officials said.

Over all, the number of full-time exorcists in the Roman Catholic Church in the United States has risen to 10 from only one a decade ago, said Michael W. Cuneo, a Fordham University sociologist whose book “American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty” is to be published next year. Mr. Cuneo writes of an “underground network” of exorcists numbering in the hundreds, and a “bewildering variety of exorcisms being performed.”

From 1989 to 1995, the archdiocese of New York examined more than 300 potential exorcism cases, although exorcisms were performed in only 10 percent of the cases, Father LeBar said. Since 1995, the New York diocese has investigated about 40 cases a year.

In addition to Roman Catholic exorcisms, an unknown number of spiritual-cleansing ceremonies are being performed by priests outside the sanctioning of the church, and by evangelical ministers and Episcopal charismatics, Mr. Cuneo said. Mr. Cuneo spent two years studying the subject and said he had witnessed more than 50 of the rituals.

Two factors are spurring the growth in exorcisms, experts said. One is popular culture; the other is a belief by some that there is more evil in the world.

As recently as the 1960’s, Mr. Cuneo said, “exorcism was all but dead and gone in the United States.”

“It was a fading ghost long past its prime,” he added. “People weren’t running to get demons expelled.”

But in 1973, the movie “The Exorcist” changed that. The movie, recently re-released, spurred an onslaught of movies dealing with demon possession and Satanism. By the mid-1980’s, there was a proliferation of exorcisms done by evangelical Protestants, Mr. Cuneo said.

Some experts surmise that the rise in demand may simply be a part of a society that has grown more accepting of therapy.

Typically, people who seek exorcism are distraught and have exhausted conventional means of relieving an inner turmoil that has long plagued them, experts said, and generally exhibit violent or other abnormal behavior. The Roman Catholic Church requires that a physician rule out the existence of a medical or psychological condition before an exorcism can be considered.

Those people who are “so wounded and broken, whether it’s drug addiction or severe sexual abuse, are incredibly desperate people who basically don’t have anywhere else to go,” Mr. Larson said.

In an exorcism, the exorcist invokes the name of Christ, blesses the person who is possessed, recites biblical passages, and commands the evil spirit to leave.

Mr. Cuneo said that most exorcisms are not a private affair between priest and patient.

“You have loved ones and a support group there and people praying for you, and you’re at the center of attention,” he said. The exorcism “can involve you wailing and moaning, perhaps thrashing on the floor, perhaps shredding hair, shredding clothing, regurgitating, perhaps flailing out.”

The New York Times

Vatican’s Revised Exorcism Rite Affirms Existence of Devil

By John Tagliabue

ROME, Jan. 26 – REAFFIRMING THAT the Devil exists and is at work in the world, the Vatican today issued a revised rite of exorcism, the Roman Catholic ritual for driving out demons.

In an apparent effort to placate liberal Catholics embarrassed by a practice that seems to echo medieval superstition, the Vatican urged those performing exorcisms to take pains to distinguish between possessed people and others suffering from forms of mental or psychological illness.

Exorcism is an ancient practice of driving the Devil from people believed to be possessed. It remains a source of theological debate and in recent years, despite its renewed popularity in the United States and elsewhere, the church has sought to play down its significance without shaking the foundations of belief in a personal source of evil in the world.

By revising the rite of exorcism, the Vatican was following a mandate of the Second Vatican Council, which met from 1962 to 1965. It also took the opportunity to urge priests and bishops to seek professional medical assistance in cases where the true nature of what seems to be diabolical possession is in doubt.

In a Latin text titled, “De Exorcismis et Supplicationibus Quibusdam” (Of Exorcisms and Certain Supplications), the Vatican cautioned that exorcists, “first of all, must not consider people to be vexed by demons who are suffering above all from some psychic illness.” It cautioned against treating as possessed “victims of imagination.”

The 84-page Latin text, which Pope John Paul II approved before he departed for his visit to North America, contains prayers and rites for driving out devils, but also for cleansing places and things of demonic influence.

Jorge Arturo Cardinal Medina Estevez, head of the Vatican congregation responsible for religious rites, said genuine possession could be recognized by various criteria, including the use of unknown languages, extraordinary strength and the disclosure of hidden occurrences or events. He also mentioned a “vehement aversion to God, the Blessed Virgin, the saints, the cross and sacred images.”

By issuing the text, which replaces a 1614 version, the Vatican reaffirmed the existence of the Devil.

Cardinal Medina Estevez acknowledged that many modern Catholics no longer believed in the Devil, but he called this a “serious fault in religious education,” adding that the existence of the Devil “belongs to Catholic faith and doctrine.”

Issuing the revised text could “provide some incentive for the appointment of more official exorcists,” said Michael W. Cuneo, a Fordham University sociologist who is writing a book on exorcism in American culture. But Mr. Cuneo said that despite a “flourishing market for exorcisms,” most Catholic bishops in the United States considered exorcism “to be antiquated, to be an embarrassment, to be a survival of medieval superstition.”

The New York Times

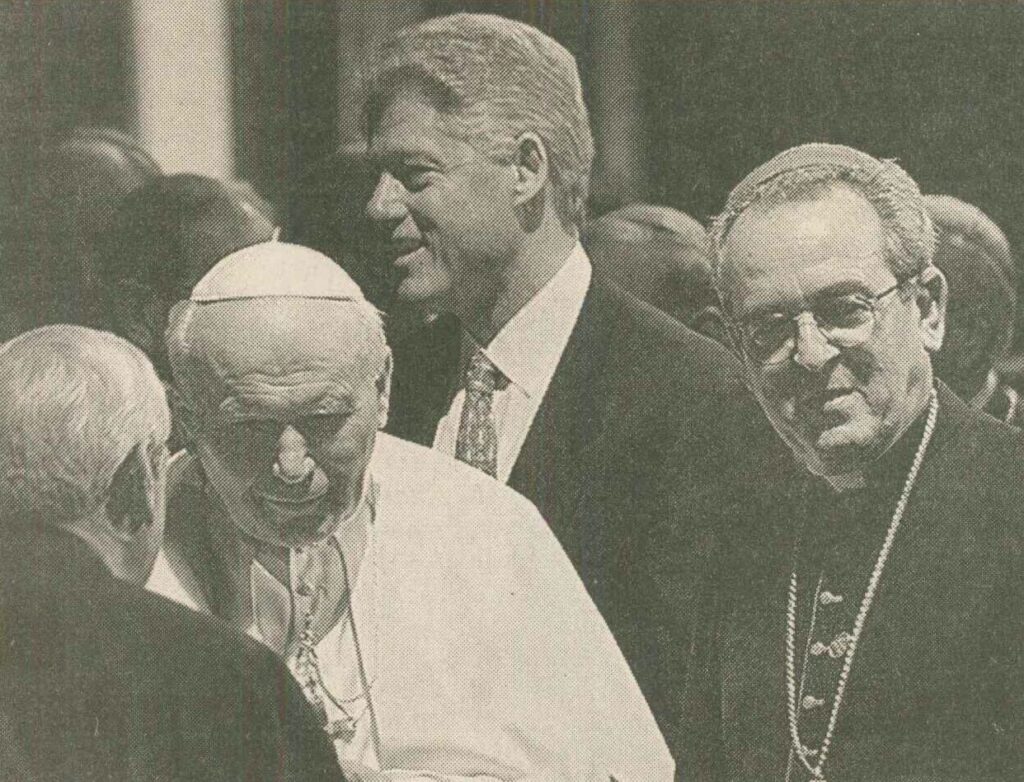

Pope’s Appeal Not Enough to Bridge Divide on Executions and Other Issues

By Gustav Niebuhr

[excerpted]

ST. LOUIS, Jan. 29 – WHEN POPE JOHN PAUL II condemned capital punishment in his brief pastoral visit here, the 100,000 people gathered before him in an indoor stadium roared with applause, not once but three times, during that section of his homily.

Despite the cheering crowds, the Pope faces a tough challenge in getting American Roman Catholics to fall into line behind him, a pontiff whom they show every sign of deeply admiring, but whose teachings many of them treat as advisory.

Michael W. Cuneo, a sociology and anthropology professor at Fordham University in New York, said this week’s events in St. Louis offered “a powerful teaching moment” for Catholic leaders, and were likely to be discussed from pulpits and in parochial schools for some time.

But Mr. Cuneo also said many American Catholics held a paradoxical view of papal teachings on major societal issues. While they are often “deeply respectful” of the Pope’s statements, many Catholics “use the teaching of the Pope as a resource, but not the only resource” in forming their own views, he said.

Sounding a similar theme, former Gov. Mario M. Cuomo of New York, an opponent of capital punishment, said he was “delighted” by what the Pope said about the death penalty.

“Will he persuade people?” Mr. Cuomo asked. “He will certainly make some people think again about the issue.”

But the former Governor also predicted that the church’s teaching on capital punishment “will receive even less compliance” than its teaching on abortion.

When the Pontiff preached against the death penalty on Wednesday, he summoned the toughest language he had yet used on this subject in the United States, calling capital punishment “cruel and unnecessary.”

Far more dramatically, he put a personal request to Gov. Mel Carnahan, after an interfaith service at St. Louis Cathedral, to spare Darrell J. Mease, a convicted killer of three people who was set to be executed on Feb. 10.

Mr. Carnahan, who has approved the executions of 26 death row inmates as Missouri’s Governor, said he was “very greatly” moved by the Pope’s appeal, enough to sign a commutation order Thursday. But the Governor said he still supported the death penalty.

The New York Times

Abortion Clinic Violence Stirs Debate Among Church Leaders

By Gustav Niebuhr

[excerpted]

THE KILLINGS OF two workers at abortion clinics in Massachusetts 11 days ago has touched off a debate among some of the nation’s most prominent Catholic and Protestant leaders over whether opponents of abortion should pull back from sidewalk protests and turn instead to prayer within church walls.

The debate reflects a concern among some anti-abortion leaders that tensions over abortion have escalated to a point that some dramatic gesture must be made to defuse them.

At the same time, a number of anti-abortion leaders have voiced concern that the broad movement is at risk of being tarnished because of the acts of a violent few. In a homily yesterday in which he decried violence against abortion clinics, John Cardinal O’Connor, Archbishop of New York, indicated that he would not follow the lead of Bernard Cardinal Law, Archbishop of Boston, who has called for a moratorium on sidewalk protest vigils outside abortion clinics in Boston.

Like other major social movements in American history, the anti-abortion movement is highly diverse, a loose coalition of organizations, informal groups and individuals. And like other movements, it incorporates moderates and militants – those dedicated to pushing the cause through law, education and huge marches, and those who register their protests directly at the clinic doors.

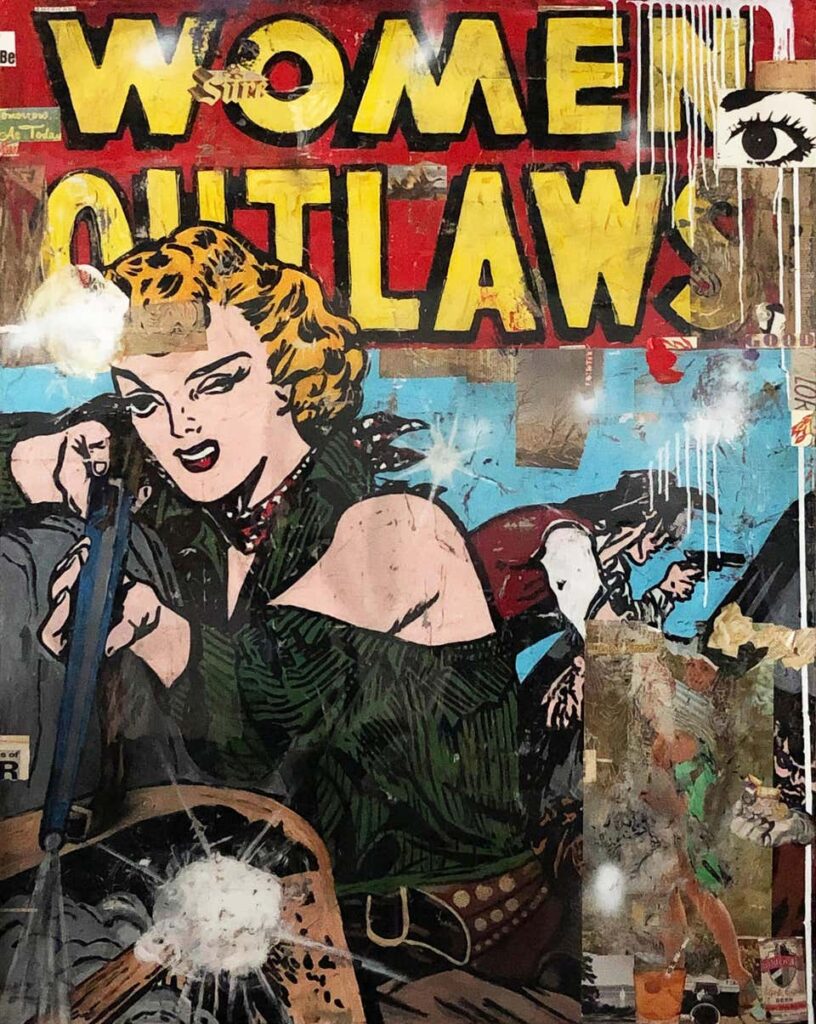

“The division between the moderates and the purists in the movement is deep,” said Michael W. Cuneo, a professor of sociology and anthropology at Fordham University, who has studied Catholic anti-abortion demonstrators. Among many of the most militant, he said, “it’s unqualified, no-holds-barred commitment.”

“You could have every bishop in this country telling them to stop it,” Mr. Cuneo added. “It would not make one iota of difference.”

New York Magazine

Winter’s Bone’s John Hawkes on His Oscar Nomination

By Nisha Gopalan

FROM AN INTERVIEW with Academy Award-nominated actor John Hawkes

In Winter’s Bone, your character, Teardrop, seems to have a good arc; he almost has a personality makeover.

What’s interesting to me is that people see that as some sort of character arc that doesn’t exist. I think he’s the same person as when you meet him. Character actors, and audiences, are always looking for the epiphany of the characters, the a-ha moment. He’s just trying to protect his family and uses different tactics throughout. I don’t think he has some kind of revelation in the movie and becomes a better person at all. That interests me. I like that the perception of the audience changes.

Did you base him on anyone?

I went to places to look for Teardrop-like people to observe. Certainly in my little town growing up, there were plenty of those there, too. Rough people. People you’d be afraid of. There’s a book called Almost Midnight by Michael Cuneo that spoke about bars that tourists shouldn’t go to that are in the [Ozarks] area. It’s a true-crime book about a meth murder — very different from Winter’s Bone. I drove to those small-town bars before I started to shoot there. I’m from a little town, so I don’t find little towns creepy. I find the people there interesting and . . . overlooked.

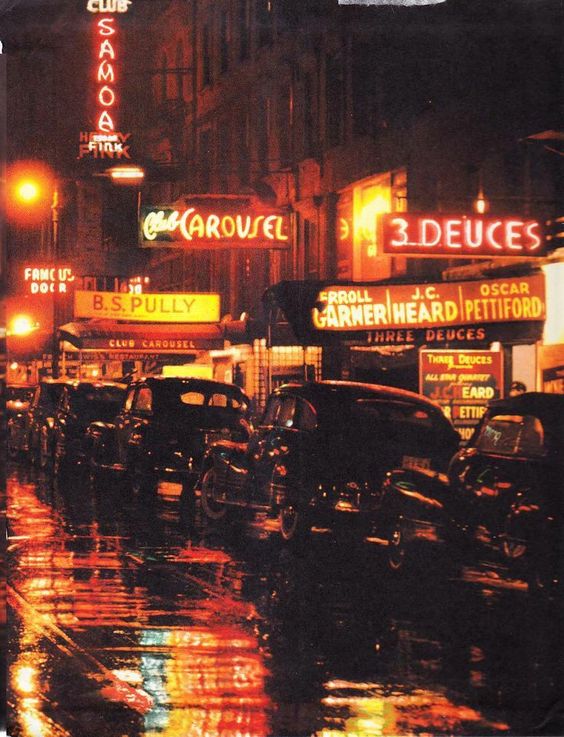

Daily News (New York City)

Exorcism, Made Easy

By Emily Gest

[excerpted]

IF THERE’S A DEVIL at work, chances are so is an exorcist.

Within the Catholic Church, a handful of exorcisms take place annually, compared with the “thousands” that take place in other faiths, said Michael Cuneo, author of “American Exorcism,” due in bookstores next week.

Before a victim is exorcised by priests, he or she is interviewed and subjected to a battery of psychological and medical tests to rule out any treatable disease.

Daily News (New York City)

Satan and the Saint

By Corky Siemaszko

[excerpted]

MOTHER TERESA believed she was possessed by the Devil, the archbishop of Calcutta said yesterday. So the revered nun, whom the Vatican hopes to make a saint, underwent an exorcism and afterward “slept like a baby,” he said.

Some doubted the archbishop’s story yesterday. The Rev. Richard McBrien, a theology professor at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, called the exorcism and the archbishop’s explanation for it bizarre.

So did Michael Cuneo, author of “American Exorcism,” which hits bookstores next week.

“You’re not supposed to proceed with an exorcism without exhaustive testing,” Cuneo said.

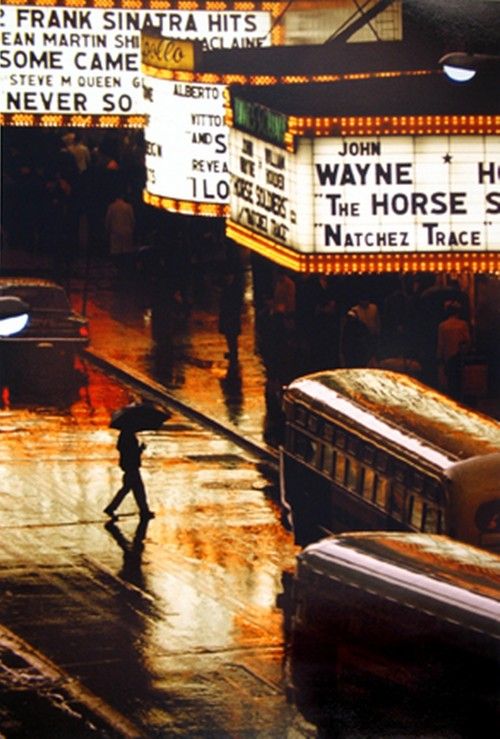

Daily News (New York City)

• Fordham University Professor Michael W. Cuneo discusses his nonfiction book “American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty,” a firsthand look at those who practice the religious ritual and those supposedly possessed.

7:30 p.m., free. Barnes & Noble, 675 Sixth Ave., at 22nd St.

(212)727-1227

New York Newsday

Editorial: In Sad Times for Church, the Spies Have It

By Bob Keeler

[excerpted]

A TINY MINORITY of right-wing zealots has been waging a tenacious guerilla struggle in the Catholic Church for years. Now that energy has interacted with a new force, the cloud of suspicion covering priests, to bring sadness and division to one Sound Beach parish. This story, so intensely local, is also a disturbing harbinger for the church as a whole.

At the center of the sad tale is the Rev. Charles Papa, the much-loved pastor of St. Louis de Montfort Parish. When some parishioners launched a chapter of Voice of the Faithful (VOTF), the lay organization that sprang up in response to the sexual abuse scandal, Papa was supportive. That took courage, because Bishop William F. Murphy sees VOTF as a threat.

This kind of zealotry is nothing new in the Catholic Church, which has a sad history of putting heretics to death. In recent times, right-wing Catholics have been only too ready to spy on, disrupt and report to the Vatican those they see as less than orthodox. And the Vatican, it would seem, has been only too willing to listen to them.

“My take is that without question they have captured the attention of the Vatican much more readily than more liberal Catholics could ever have hoped to do,” said Michael Cuneo, a Fordham University sociology professor and author of “The Smoke of Satan,” a book about the Catholic right, and “American Exorcism,” about fascination with demonic possession. “They have succeeded in fashioning an influence for themselves out of proportion to their numbers.”

Los Angeles Times

Exorcism Flourishing Once Again

By Teresa Watanabe

[excerpted]

THE ANCIENT RITUAL of exorcism, which fell out of favor in the Age of Reason, is once again flourishing in the Age of the Internet.

End-of-the-world fears? A desire stoked by Hollywood occult films? Ministers looking for new lines of work?

Whatever the cause, hundreds of exorcism ministries now exist – some with names like Demon Stompers that offer personal deliverance testimonies and toll-free lines for convenient counseling.

The Catholic Church in the United States has quietly increased the number of appointed exorcists from just one in 1990 to between 15 and 20 today, according to Michael W. Cuneo, a Fordham University professor and author of a soon-to-be-published book, “American Exorcism.” Moreover, Cuneo says, countless maverick priests are performing bootleg rites without their bishops’ required permission.

But the number of Catholic exorcists pales next to those in the world of charismatic and evangelical Protestantism, Cuneo says. Among theologically conservative evangelicals alone – those who don’t believe in speaking in tongues and other Pentecostal gifts – Cuneo says exorcism ministries have skyrocketed from a handful in the early 1980s to more than 600 today.

The Fordham scholar has personally witnessed more than 50 exorcisms – most of them performed out of genuine spiritual compassion with no demand for fees, he says.

Cuneo partly attributes the apparent rise in exorcism requests to popular culture. From the 1973 release of the movie, “The Exorcist,” which was re-released last month, to Harry Potter books today, an endless string of films, books and TV talk shows has made the occult part of general discourse, he says.

Geraldo Rivera, Oprah Winfrey, Larry King and Barbara Walters have all featured exorcists on their shows, Cuneo says.

“Should we not think that exposing people relentlessly to this talk of demons wouldn’t have some effect?” he says.

The Philadelphia Inquirer

Deliverance Ministry Keeps Him Busy

By Jim Remsen

[excerpted]

BELIEF IN DEMONIC FORCES is not far-fetched, according to a Gallup Poll released earlier this year. Fully 68 percent of Americans believe in the devil, it found, while 20 percent do not, and 12 percent are unsure.

Many charismatic Christians claim “heightened spiritual sensitivities” as “humanity’s advance guard into the spirit world,” said Michael Cuneo, a Fordham University sociologist and author of a definitive book on the subject, “American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty.”

In researching his book, Cuneo found that there are at least 600 deliverance ministries in the United States, and there could be triple that number.

Cuneo, a skeptic, found that the Pentecostal and charismatic world fell into “demonomania” in the 1970s and 1980s, inspired in part by “The Exorcist,” the 1973 film said to dramatize a Catholic exorcism.

Those were the early boom years of the charismatic movement, and zealous exorcism and deliverance ministries were common, Cuneo said. But in time, he said, the marathon “puke and rebuke” sessions, and occasional medical emergencies, caused a backlash. A competing method emerged that aimed to simply “bind the demons.”

Cuneo’s book explains the thinking: “Demons needed to be kept in their place, the subjects of deliverance needed to be restrained from acting out, and it was the responsibility of deliverance ministers to ensure that proceedings were conducted in a dignified manner.”

Cuneo said he talked to many people who claimed relief through deliverance. While not dismissing them all outright, he said he believed many apparent cures resulted from “auto-suggestion” or as a placebo effect, in which the mere act of being treated provides relief.

Austin American-Statesman (Texas)

Exorcisms Aren’t Rare, Writer Says

They’re easy to set up if you’re not too picky or too fussy, he says

By Shel Via Dancy (Religion News Service)

MICHAEL CUNEO has seen grown women and men thrashing wildly on the floor in tantrums worthy of a sandbox.

He’s seen adults, who you might otherwise think were models of middle-class decorum, convulsing and screaming obscenities.

They all are raising hell to banish their inner demons.

“I think exorcisms are being performed to a much greater extent than the public imagines,” said Cuneo, a front-row witness himself to more than fifty exorcisms and author of the new book “American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty” (Doubleday, $24.95). “That’s partly why I decided to commit myself to writing a book about it – the public really has no idea.”

Brought to light

Not until Linda Blair’s jolting portrayal of demonic possession in the 1973 horror classic “The Exorcist” did the topic slip onstage, Cuneo argues in his book. Before then, the issue barely roused notice.

“There were some charismatics and Pentecostals performing exorcisms, but it was not a big deal; even the major Pentecostal denomination in the U.S. was a bit embarrassed about it,” said the Fordham University anthropology and sociology professor. “Exorcism ministries were rare, and there was marginal public interest at best.”

But the film turned heads, and several copycat movies plus nationwide allegations of satanic child abuse at day-care centers in the 1980s stoked national interest so that “by the end of the ‘80s it was hard to turn on daytime TV without encountering this stuff – Geraldo, Oprah, Donohue. Even Ms. Magazine had a completely uncritical feature article on it.”

“A great many people – and not just evangelicals – believed that there was a vast satanic conspiracy in the land and that Satanists were abducting children off the street and subjecting them to horrible ritual abuse,” Cuneo said. “These claims of satanic abuse and abduction were often taken at face value, and as a result there was an explosion of exorcism ministries throughout the United States. All of that really galvanized popular interest in exorcism.”

The popularity is still thriving, Cuneo claims, pointing to the frenzy that greeted the release of the director’s cut of “The Exorcist.”

“For two weeks there was wall-to-wall coverage and it became a sensation all over again – the popular media could not get enough of it,” he said.

Demons, be gone

Cuneo has fielded offers to have his own “demons” expelled.

“A number of times I thought, ‘yeah, this would be interesting,’ but it would have meant crossing an ethical boundary,” he said.

Snagging an exorcism of your own is not difficult at all “if you’re not going to be picky or fussy,” Cuneo said.

“If you’ll take any kind of exorcist, then it’s very easy. Because it’s so difficult to obtain an officially sanctioned Roman Catholic exorcism, a number of people have stepped in to fill the demand,” he said.

Though the number of Roman Catholic exorcists in the country has increased to about a dozen within the past year, “if you’re absolutely committed to the idea of a Catholic exorcism, then your chances are much better if you satisfy yourself with an exorcism performed on the sly by some maverick priest without any kind of episcopal approval.”

Arizona Republic (Phoenix)

Republic staff

EACH YEAR BRINGS a throng of new books. We have assembled a panel of 13 people, including a librarian, an educator, a short-story writer, a poet and a critic or two, to identify this year’s most noteworthy.

• MYSTERIES/THRILLERS

“In the Night Room,” by Peter Straub. Enter at your own risk.

“Almost Midnight: An American Story of Murder and Redemption,” by Michael W. Cuneo. True (and truly disturbing) story of drugs and violence in Missouri’s Ozarks.

“Skinny Dip,” by Carl Hiaasen. Wetlands, crooks, wealth, a cruise.

“Destination: Morgue!” by James Ellroy. Searing nonfiction pieces make up for less interesting novellas.

Publishers Weekly

The Year in Books

THIS IS THE debut of PW’s “The Year in Books,” an annual review examining noteworthy trends in books and publishing. This approach includes highlighting titles that we discern to be of exceptional quality.

• RELIGION

“Buddha,” by Karen Armstrong (Viking). Lacking details for a conventional biography, Armstrong turns this to her advantage, opting to enhance Gotama’s story with the broad canvass of his time and culture, making him accessibly human.

“American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty,” by Michael W. Cuneo (Doubleday). Lucidly written and riveting as any horror novel, Cuneo’s excursion into the darker paths of American faith offers a deeply disturbing, ironic vision of the unintentional consequences of popular culture for the modern religious imagination.

“A New Religious America: How a “Christian Country” Has Become the World’s Most Religiously Diverse Nation,” by Diana L. Eck (Harper San Francisco). Eck delivers a stunning tour de force that may forever change the way Americans claim to be “one nation, under God.” This is not just a book; it is a celebration.

St. Louis Magazine

A Family Erased: The Chris Coleman Story

By Jeannette Cooperman

[excerpted]

THE COLEMAN trial begins Monday, April 25. Waiting to go through the metal detector, the TV reporters twitch a bit, their banned cellphones a phantom limb. Post-Dispatch columnist Bill McClellan stands in line with the people of Monroe County, chatting amiably, until circuit clerk Sandy Sauget shoos him across the hall to the media line. Yusuke Hirose, a visiting scholar who’s a judge in Japan’s Kobe District Court, is here; so is Chris O’Connell of CBS News’ 48 Hours Mystery; so is Michael Cuneo, a sociologist from New York who’s writing a book about the case.

Daily Press (Newport News, Virginia)

Outcast Catholics Reject Reforms

The Associated Press

[excerpted]

Carrollton, Virginia • THE PARISHIONERS of St. Augustine’s Roman Catholic Church consider themselves traditionalists. To Catholic leaders, however, they are renegades.

Mass at St. Augustine’s is celebrated in Latin, using a liturgy unchanged for more than four centuries.

Women kneel in prayer in the tiny white chapel in Isle of Wight County, their heads draped in black lace mantillas. The priest turns his back to his congregation, facing an elaborately carved wooden altar.

St. Augustine’s is one of two breakaway Catholic congregations in southeastern Virginia. Like the congregation of Immaculate Conception Mission in Virginia Beach, the traditionalists of St. Augustine’s think that they are the true believers and defenders of the Catholic faith.

They reject the modernizing reforms of the Second Vatican Council of 1962 to 1965, and claim that the “New Mass” has lost its reverence and meaning.

“Traditionalists are separating from the official Roman Catholic Church because they believe it’s a derelict institution,” said Michael W. Cuneo, professor of sociology at Fordham University in New York City and author of The Smoke of Satan.

“They are convinced it has become hopelessly corrupted by the poison of modernity: ecumenism, secularism, humanism.”

Traditionalists account for a small fraction of Catholics. As of 2001, there were probably fewer than 50,000 separatists in the United States, out of a total Catholic population of 61.2 million, Cuneo said.

ABC News

Exorcism Thriving in U.S.

By Oliver Libaw

[excerpted]

THE DEVIL MUST be busier than ever.

Exorcism, the ancient rite of casting out Satan and his demons from the souls of the possessed, is thriving in America.

“Exorcism is more readily available today in the United States than perhaps ever before,” writes Michael Cuneo, a sociologist at Fordham University, in his newly published book, American Exorcism.

Cuneo suggests that though the hit book and movie “The Exorcist” brought the subject national attention in the 1970s, exorcism has grown more popular in the past two decades.

The Catholic Church has at least 10 official exorcists around the United States, nine more than a decade ago, Cuneo says. He found them reporting the kind of bizarre supernatural behavior featured in movies: levitation, mysterious scars and wounds that might form pictures or spell out hateful words, and more.

The church remains extremely cautious in approving the procedure. The vast majority of exorcisms today are performed by a variety of protestant religions, Cuneo says.

“By conservative estimates, there are at least five or six hundred evangelical exorcism ministries in operation today, and quite possibly two or three times this many,” he writes, in addition to numerous exorcisms performed by charismatic, Pentecostal and other brands of Christianity.

Exorcism has caused a number of real-world tragedies over the years, however, including several deaths.

Pentecostal ministers in San Francisco pummeled a woman to death in 1995, as they tried to drive out her demons.

In 1997, a Korean Christian woman was stomped to death in Glendale, Calif., and in the Bronx section of New York City, a 5-year-old girl died after being forced to swallow a mixture containing ammonia and vinegar and having her mouth taped shut.

Cuneo reports that a Wisconsin woman successfully sued her psychiatrist in 1997, after he diagnosed her as diabolically possessed, and having 126 personalities, including the bride of Satan and a duck. The experience left her suicidal, she claimed.

Overall, many involved in exorcism say the prayers and rituals involved are safe and may offer some comfort to true believers who are not actually afflicted by demons.

The Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Washington)

‘The Exorcist’ spotlights rite for banishing evil

By Kelly McBride

[excerpted]

AFTER “THE EXORCIST” was released in 1973, demand for the ancient Roman Catholic ritual skyrocketed – creating a black market in driving out demons.

It’s happening all over again. The movie was rereleased and opens today – Friday the 13th – at theaters in Spokane and Coeur d’Alene. Exorcisms are back, too.

“Exorcism was practically a dead issue until the movie first came out in 1973,” said Michael Cuneo, an anthropology professor at Fordham University in New York. “Even most Pentecostal churches were toning it down, trying to get out of the demon-expulsion business. The movie changed all that.”

Ever since, there has been a public fascination with evil personified, said Cuneo, who witnessed more than 50 exorcisms during research for his book “American Exorcism,” due out next year. Finding modern-day exorcisms in any community is as easy as asking around at area churches, he said.

The movie, and dozens of others that followed, helped to create a public obsession with the devil that continues almost 30 years later, Cuneo said. The rerelease of the film has been accompanied by an increase in requests to Catholic officials for exorcisms.

“It’s amazing how much the entertainment industry can influence religious beliefs,” Cuneo said.

For at least a century before the movie was released, the trend in most Christian religions was to downplay the devil, talking instead about the existence of evil in less specific terms, he said.

There is no official Catholic exorcist in Spokane. But in 1975, some students at Gonzaga University were convinced the Monoghan Mansion, which houses the music department, was possessed.

A Jesuit priest said he prayed over the house, specifically the basement, but did not perform an official exorcism.

The Roman Catholic Church allows exorcisms only when all physical and psychological causes for behavior or occurrences can be ruled out.

Because official Catholic exorcisms are so hard to come by, “bootleg” ones are rampant, Cuneo said.

People committed to obtaining an exorcism can simply ask around or hop on the Internet. “Eventually you will find lots of options. You can comparison shop,” Cuneo said.

In all the exorcisms that Cuneo has attended, he said he has never witnessed incontestable evidence of demonic presence.

“But oftentimes I was the only room in the room who didn’t,” he said.

The power of suggestion can be heightened in almost any religious ceremony. During exorcisms, that suggestive power is so intense it can be dangerous or healing, Cuneo said.

“I have seen the procedure have actual therapeutic effect. It can be a catharsis, he said. “I have also seen exorcisms that I would assess as damaging.”

Tulsa World (Oklahoma)

Catholic Priest is a Trained Exorcist, Calls for His Services are Increasing

By Bill Sherman

[excerpted]

THE SATANIC ‘black mass’ scheduled Sunday at the Oklahoma City Space Theater has drawn attention to a little-known but rapidly growing ministry in the Catholic Church: exorcism.

Tulsa is one of three cities in the United States where Roman Catholic priests meet regularly to be trained to cast out demons, training that is part of a recent movement in Catholicism to expand that ancient ministry.

Exorcism conferences have been held quietly each winter for three years at an undisclosed chapel in Tulsa, following a decision by U.S. bishops in 2010 to greatly increase the number of exorcists in America, at that time thought to be about 50.

“The number of Catholic exorcists in America has doubled every year for the past three years,” said Monsignor Patrick Brankin, the Diocese of Tulsa’s only exorcist.

The ministry of exorcism assumes the existence of a real and personal Satan, and actual demons that can possess human beings, which is the historical position of the Catholic Church and many evangelical Protestants,

Fordham University sociologist Michael Cuneo, in his recently published book, “American Exorcism,” said that most exorcisms in the United States are performed by various Protestant groups.

“By conservative estimates, there are at least five or six hundred evangelical exorcism ministries in operation today, and quite possibly two or three times this many,” Cuneo wrote.

Bishop Edward J. Slattery of the Diocese of Tulsa named Monsignor Brankin an exorcist more than four years ago in response to a local case of demon possession.

When that case came up, Brankin said, the diocese was unable to find an exorcist to handle it, and he agreed to go see the person, even though he had not yet been appointed as an exorcist.

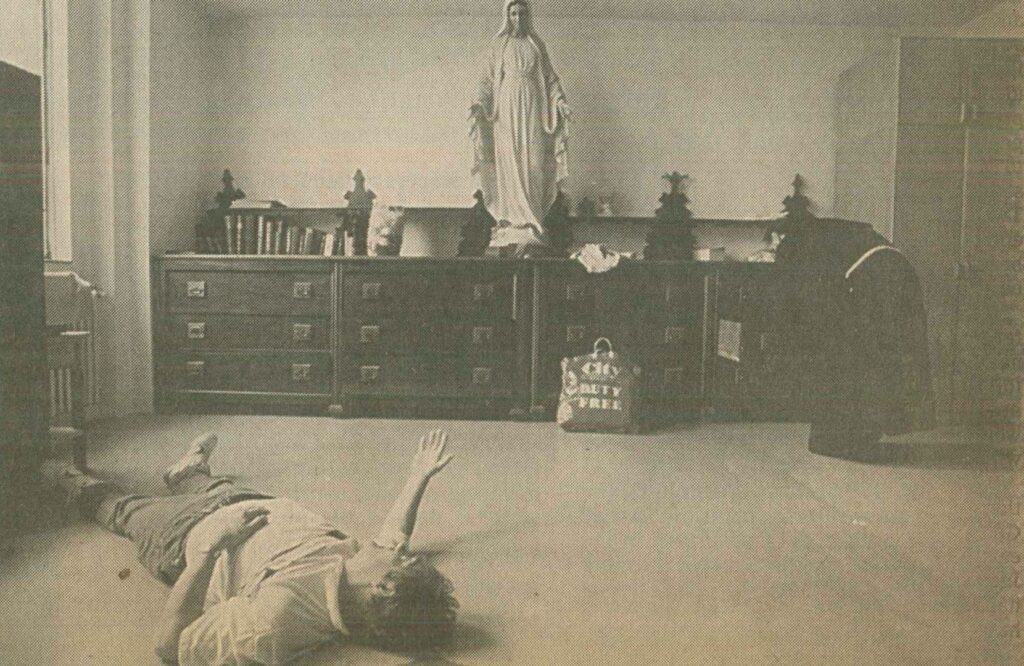

He found the person crouched in a corner of a room.

Brankin said the demon in the person immediately recognized him as a priest, without looking at him, and pronounced smugly that it knew Brankin had not been given the authority to exorcise it.

“That scared me,” Brankin said.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram (Texas)

Casting Out Demons

By Malcolm Mayhew

[excerpted]

AS INTEREST IN exorcisms has soared, so has the number of sanctioned exorcisms. According to author Michael Cuneo, the number of official Roman Catholic exorcists has grown from one or two in 1995 to 15 or 20 today. And that’s just the sanctioned exorcisms.

The number of those performed by non-Catholic religious leaders is uncountable. Cuneo guesstimates that between those performed privately in homes by pastors from various faiths, “underground” exorcisms performed by bishops without church permission (permission is necessary for official exorcisms) and mass deliverances done by televangelists such as Bob Larson, the number could be in the thousands per year.

While researching his recently released book, American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty, Cuneo says he attended about 50 exorcisms, in places varying from churches to homes to arena-size venues where clusters of people were exorcised simultaneously.

And he still isn’t convinced he saw unmistakable evidence of the demonic.

“I saw lots of fireworks, lots of dramatic activity,” Cuneo says. “Thrashing and howling and wailing, shredding of clothes, simulated masturbation, writhing on the floor – but nothing in my mind that could not be accounted for in social, medical or psychiatric terms.

“I didn’t see the stuff a lot of people were hoping I’d see – the levitating bodies, the spinning heads, the demonic grotesquerie,” he says. “Some people would tell me that the reason for this is because Satan knows I’m a writer and he didn’t want to blow his cover.”

Not that Cuneo necessarily dismisses the idea of demons and demonization. But in his book, he says more people are turning to exorcists because they need an explanation for their erratic behavior. And raised on movies like The Exorcist and The Amityville Horror, people think demon possession is a good excuse to justify their misdeeds or problems,

“It’s the ultimate victimization,” Cuneo says. “People who can’t or do not want to take responsibility for their actions, they can say they’re under the sway of demons.”

Fort Worth Star-Telegram (Texas)

Interest in Exorcism Surges Due to Film’s Re-Release

By Nancy Haught (Religious News Service)

[excerpted]

MICHAEL W. CUNEO would be happy to answer a few questions about exorcism, but first the Fordham University sociologist wants to know what’s been going on. He’s been out of town and returned to his office to find his voice mail clogged with questions about exorcism.

A surge in demonic possessions? Possibly. But probably just a surge in media interest sparked by the recent re-lease of The Exorcist, William Friedkin’s 1973 film inspired by a real-life exorcism of a 13-year-old boy.

The re-release of the movie comes on the heels of news reports that Pope John Paul II performed an exorcism on a 19-year-old woman last month.

After years during which the official church didn’t speak much about demons, possession or the centuries-old rite of exorcism – the process of expelling demons from a person – John Paul II has been forthright about the practice. He has publicly denounced the devil as a “cosmic liar and murderer,” overseen the first revisions in the church’s official rite of exorcism in three centuries and taken part in exorcisms himself.

Now, the re-release of The Exorcist has revived popular interest in the relatively obscure practice and raised concerns about its misuse.

All of which might explain the glut of messages on Michael Cuneo’s voice mail. Cuneo has emerged of late as an expert on exorcism in the United States. Over the past two years, he has attended about 50 exorcisms, conducted in a variety of circumstances and settings. He has witnessed both officially sanctioned and “underground” exorcisms conducted by Catholics and Protestants. Earlier this month, he delivered a manuscript containing his findings to Doubleday, which plans to publish American Exorcism next fall.

“I did not see any spinning heads or levitating bodies,” Cuneo said. “But there were times when I was the only person in the room who didn’t see these things.” Pressed for details, he refused to elaborate. No trespassing on his book, he insisted. But he’s more than happy to talk about The Exorcist.

Cuneo expects the film to increase popular demand for exorcisms, just as it did the first time it hit movie theaters. But he sees no reliable way to measure that demand.

“The kind of exorcism in hottest demand is an official Catholic one,” he said, “but it’s very hard to obtain.” Most dioceses do not have designated exorcists, and church law requires an extensive investigation before a bishop can authorize an exorcism.

The result, Cuneo says, is a growing demand for unofficial, or underground, exorcisms. “It’s difficult to know precisely how many have been performed.”

The Charlotte Observer (North Carolina)

‘Duking it out with Demons’

By Ken Garfield

[excerpted]

CHRISTIAN EVANGELIST and self-described exorcist Bob Larson will hold what he calls a “Spiritual Freedom Conference” at 7 p.m. today at the Charlotte Marriott Executive Park.

Larson, 58, appreciates the chance to demystify something he said he’s been doing 30 years. Exorcism, he said, has to do with taking a person back to the source of their pain, then leading them toward getting rid of what he calls demonic forces that caused the problem. A person often begins to speak in weird or unintelligible language after going back to where and when the hellish moment in their life took place, he said.

An exorcism, he said, can take from 15 minutes to two hours.

Fordham University professor Michael Cuneo studied Larson for his recently released book, “American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty” (Broadway). Cuneo said he’s suspicious of exorcists and some of the claims they make.

Cuneo, who witnessed 50 exorcisms researching his book, said the practice endures because we live in a culture where people are desperate for a quick-fix cure. It’s also a no-fault culture where it’s easier to point the finger at the devil: “It’s not myself, Mike Cuneo, who’s to blame,” he said. “It’s my demons.”

Cuneo said the crying, trembling and wailing that goes on at an exorcism comes from people desperate to be healed.

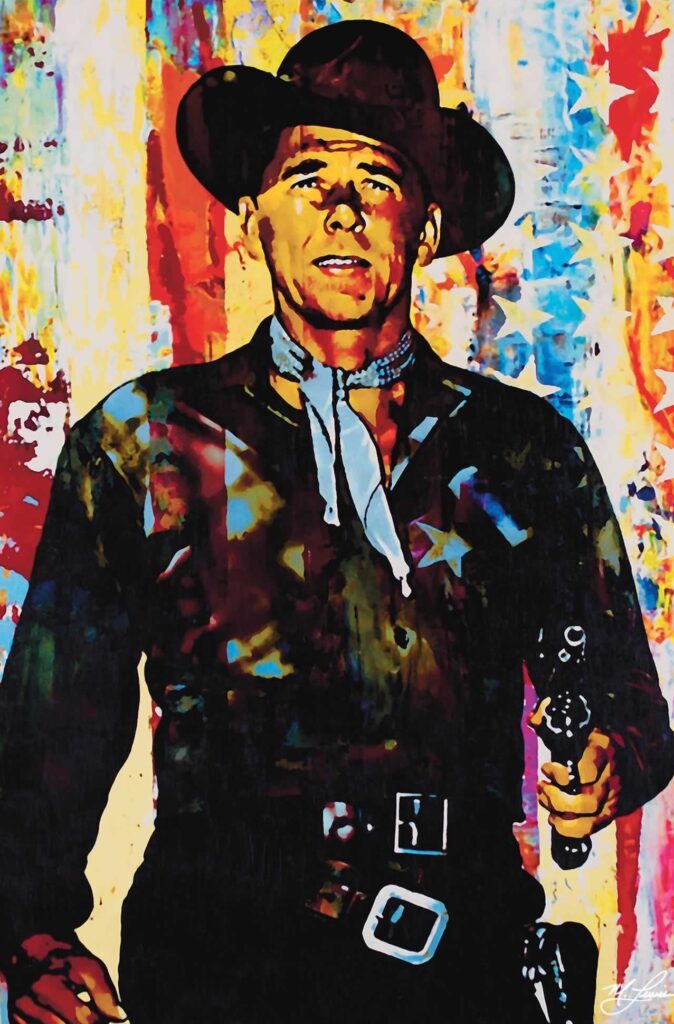

“You don’t want to disappoint,” he said. “You have a guy working and sweating for you . . . Guys like Larson truly believe they have a calling to do battle with supernatural evil. It’s like the final frontier – the lone gunman duking it out with demons.”

Edmonton Journal (Alberta)

Sunday Pick

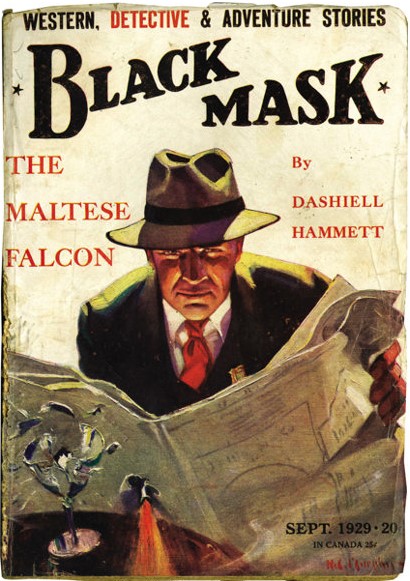

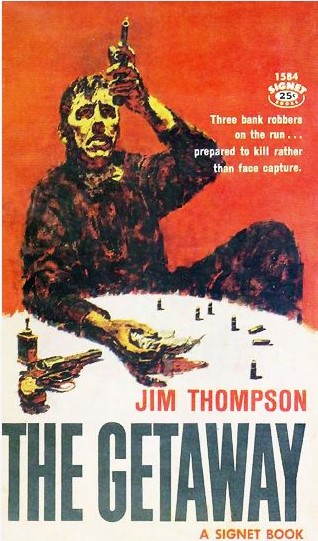

Almost Midnight: An American Story of Murder and Redemption, by Michael W. Cuneo (Broadway Books)

By Marc Horton

DARRELL MEASE, who shot 69-year-old drug kingpin Lloyd Lawrence, Lawrence’s wife and teenage son to death almost 10 years ago, was unmistakably a low life. Addicted to crystal meth, he dealt in the drug, led a violent life and was one of those doomed souls who live without hope. He was a man of little or no compassion.

A lifetime spent in the Ozarks had given him the kind of prickliness that is almost constantly on the cusp of violence.

After his arrest, it seemed a certainty that Mease would be convicted of the Lawrence murders, and be condemned to die by lethal injection in prison.

All of this might make for a tawdry story of a loathsome man who deserved capital punishment.

However, investigative reporter Michael Cuneo, who also wrote the acclaimed American Exorcism, has dug into the Mease case and found a story of redemption.

Mease, who underwent a conversion while in the death house, predicted his life would be miraculously spared by the intervention of God himself.

While that didn’t happen, Pope John Paul’s plea to the governor resulted in a commutation of Mease’s sentence.

A page-turner, Almost Midnight introduces readers to life in the Ozarks and to dozens of unforgettable characters as well.

The Wichita Eagle (Kansas)

A Look at Devilish Developments

By Tom Schaefer

WITH THE RELEASE of such films as “End of Days,” “Bedazzled,” “Little Nicky,” and the rerelease of “The Exorcist,” are we in for another round of satanic excess?

Don’t misunderstand: I believe in the reality of evil. But I also recall how exaggerated it can be. Twenty years ago, there were claims of bizarre rituals using animals and kidnapped babies by groups of Satan worshippers. Few if any of those claims could be verified.

Author Michael Cuneo, whose book “American Exorcism” is due out soon, said there are more than 600 exorcism ministries today. The Roman Catholic Church has between 15 and 20 appointed exorcists in the United States, Cuneo says.

In his preface to “The Screwtape Letters,” an imaginary correspondence between a senior devil and his apprentice, the British writer C.S. Lewis opined that there are two errors that people can have about demonic beings: “One is to disbelieve in their existence. The other is to believe, and to feel an excessive and unhealthy interest in them.”

Will we see the pendulum swing toward the excessive and unhealthy interest? I hope not.

The Boston Globe

Atheists Claim Freedom From Religion

By Joseph P. Kahn

[excerpted]

BOSTON PLAYED host over the weekend to the national conference of American Atheists. Founded in 1963 by Madalyn Murray O’Hair, American Atheists claims a membership of 2,000 and tackles a range of First Amendment issues. Conference speakers included actor and writer John Bloom (also known as TNT film critic Joe Bob Briggs) and author Michael Cuneo (“American Exorcism”).

SF Weekly (San Francisco)

Return of the Devil: Exorcism’s Comeback in the Catholic Church

By Chris Roberts

[excerpted]

EXORCISM IS BACK. This seemingly medieval practice — which fell by the wayside as the Church attempted to modernize in the last 50 years, and which took a further hit in 1973, when a young German woman, Anneliese Michel, died after undergoing repeated exorcisms — is creeping into the Catholic mainstream once again. This assertion is repeated in headlines in the Telegraph, U.K. Guardian and other news publications that talk of an “exorcism boom.”

“Almost all exorcists are unanimous in their belief that more people are becoming possessed today than in the recent past,” writes journalist Matt Baglio in The Rite: The Making of a Modern Exorcist, a tome inspired by (and centered on) Thomas’s training in exorcism, undertaken in Rome in 2005.

Skeptics would point out that such a statement is akin to umbrella salesmen agreeing that it’s about to rain. And there are many skeptics. Michael Cuneo, a professor at Fordham University in New York City, attended 50 exorcisms while researching his book American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty. And “never once did I walk away convinced that the person being exorcised was really demonized,” he said in an interview with Evangelical Today.

The Cincinnati Post

Demon Buster

By Barry M. Horstman

[excerpted]

BOB LARSON, a self-styled “spiritual warrior” and veteran of hundreds of purported exorcisms, paced the stage at The Church in College Hill and prepared to again do battle with an old, familiar foe: the devil.

It wasn’t going to be easy or pleasant, he warned the nearly 500 faithful in the audience – though not because of any images Hollywood may have planted in their minds. “No heads are going to spin around, and no one’s going to spit up pea soup,” he said.

But the standing-room-only crowd saw plenty of other demonic action Wednesday night.

Whether spawned by end-of-the-world fears, an intrigue stoked by occult films or a force attributable to other biblical or psychological sources, exorcism – the ancient ritual of casting out Satan and his demons from the souls of the possessed – is thriving in America.

“Exorcism is more readily available today in the United States than perhaps ever before,” said Fordham University sociologist Michael Cuneo, author of a new book titled “American Exorcism.”

Contexts

The devil’s playthings

By Mary Jo Neitz

[excerpted]

IN AMERICAN EXORCISM, Michael Cuneo explores an as yet neglected facet of the current spiritual renewal in the United States.

Cuneo, who has written previously about conservative Catholic sects, now turns his investigative skills to Christian rituals that address demonic possession. He examines a range of groups that practice exorcism and deliverance in order to enable individuals ostensibly afflicted or possessed by demons to return to normal lives.

American Exorcism gives readers the thrill of voyeuristically traveling the country and experiencing exorcism and deliverance in many different settings. At the same time, one has the reassuring companionship of the ultimately skeptical Cuneo. With titillating prose, he describes individuals who believe they are possessed brawling, vomiting, screaming, and slithering like snakes in classic scenarios. He also includes more mannerly gatherings: groups that don’t tolerate such bad behavior and “bind” the demons before the deliverance. He reports on his conversations with exorcists and their assistants, in some cases psychologists, in other cases those with the gift for discerning spirits.

After personally witnessing over 50 exorcisms, does Cuneo believe in demon possession? In the conclusion he says he didn’t see any demons, and yet he does suggest reasons why exorcisms might work, just the same.

Cuneo’s tale starts not with “exorcism” in the anthropological sense of a ritual practiced in many cultures throughout the world, but with The Exorcist, William Blatty’s best-selling book and the popular movie derived from it. This is consistent with Cuneo’s thesis that the current interest in demon possession is largely driven by popular culture, starting with Blatty’s account, and then followed by other movies and books over the past 40 years.

Cuneo’s informants include Roman Catholics and “traditionalist Catholics,” Pentecostals and Neo-Pentecostals, and evangelicals of both the new and old schools. Yet, part of what has captured Cuneo’s imagination in Blatty’s version of exorcism is the presence of priest-heroes with “enormous spiritual fortitude.” Although what he finds in the field cannot match the action in the movies, Cuneo continues to search throughout the book for the real-life priest-heroes.

Cuneo reports that interest in exorcism had nearly died out in the American Catholic church 60 years ago. By the middle of the twentieth century no diocese had an officially appointed exorcist. Following the release of Blatty’s novel and the film, the church was overwhelmed by requests for what most clerics regarded as an outdated ritual. Ex-priests, some Protestant ministers, and deliverance ministry teams developed special practices in response to the failure of the Catholic church to meet the demand. Somewhat reluctantly, in the mid-1990s, Catholic bishops began to appoint official exorcists in some dioceses. (Cuneo reports that 10 were appointed in 1996.) For Cuneo, American exorcism is “back by popular demand.”

Although he emphasizes the importance of the movie industry, Cuneo also argues that exorcism and deliverance fit with contemporary American culture. Exorcism is cheap and easy therapy. While individuals who are “possessed” have little responsibility for their unhealthy behaviors, the ritual itself is often followed by recommendations for psychological counseling and behavior changes.

●

Scholars of religion and religious practitioners have both noted that differences of denomination now often matter less than which side of a conservative/liberal divide one is one.

Cuneo [whom Andrew Greeley lauds as “the best investigative sociologist in the country”] takes one belief, the belief in an active, personal devil, and through his investigations of cultural practices organized around that belief in a variety of conservative Christian cultures, we get a tour of the conservative side of the theological divide. Along the way, we see how cultural practices move among Catholics, mainline Protestants, Pentecostals and Evangelicals.

Newhouse News Service

Both Sides Trying to Eliminate Violence from Abortion Dispute

By Delia M. Rios

[excerpted]

THERE IS A SENSE, as the nation marks the 32nd anniversary of Roe vs. Wade, that this country has reached a great divide in the moral, religious, ethical, legal and political struggle over abortion.

We have been brought here, as the struggle has turned from a shouting to a shooting war, by those on the fringe of the anti-abortion movement, the ones mainstream leaders call fanatics and dismiss as unworthy of being called “pro-life.”

A growing realization is emerging that the country may be at a critical moment in the history of the abortion debate, a moment in which there is a chance to turn away from the acrimony that has given rise to violence and to seek some accommodation.

There is weariness among mainstream groups on both sides with the violence and a common interest in stemming it. The key may lie in their ability to reclaim the public stage wrested away by the violent.

●

The collective problem remains that the tactics of those on the fringe – whether they are called purists, militants or terrorists – have succeeded in one regard.

“Radical militants believe that when they protest, they keep the anti-abortion or pro-life idea alive. In a sense, they’re right,” says Michael W. Cuneo, a professor of sociology and anthropology at Fordham University in New York and author of “Catholics Against the Church.” He has studied Catholic anti-abortion protestors in the United States and Canada for a decade.

Yet, Cuneo says, what also happens is that “lunatics surface from the woodwork. And all the people out in the streets protesting wind up unwittingly contributing to their own demonization.”

Even if that happens, Cuneo is sure of one thing:

“I’m absolutely convinced that the public protest will continue,” he says. “I’d stake my reputation as an anthropologist on it.”

For the purists, Cuneo says, “Protesting abortion is so central to their spiritual and religious commitment in the modern world.”

Miami Herald

By Rachel Zoll (Associated Press)

[excerpted]

THEY ATTEND Mass in Latin, using a liturgy Rome abolished. They abstain from meat on Fridays and women cover their heads in church. For more than four decades, a small group of American Catholics has been quietly worshipping in ways the Vatican told them to abandon.

The movement, known as traditionalist Catholicism, grew worldwide from opposition to the modernizing reforms of the Second Vatican Council, a series of meetings held from 1962-65 that dramatically changed the church.

The movement is as diverse as the many splinter groups it has generated, from moderates who maintain some contact with the Vatican to the more militant who rejected outright the authority of the late Pope John XXIII – who convened the council – and every pope elected thereafter.

There is another, even more extreme faction that believes the council was a conspiracy between Jews and Masons to destroy the church. Some go as far as considering all the popes elected since that meeting as “precursors to the anti-Christ,” according to Michael Cuneo, a Fordham University professor who wrote The Smoke of Satan, a book on traditionalists.

Daily Chronicle (De Kalb, Illinois)

By Chris Rickert

[excerpted]

MICHAEL CUNEO’s driving thesis in the titillatingly titled “American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty” is simple enough.

Exorcism and its less ritualistic younger sibling, deliverance, are thriving in the technologically advanced, secularist culture of turn-of-the-century America, he says, thanks in large part to the popular media’s fascination with the subject and a malleable population eager for new-age healing and alternative therapies.

For Cuneo, William Peter Blatty’s 1971 novel “The Exorcist,” along with the 1973 movie of the same name, was key to the rebirth of this ancient practice. And in something of an ethnographic tour, he goes from coast to coast detailing all the different forms exorcism has taken over the past 30 years – from the formal exorcism performed by the Catholic priest, to mass deliverances in which whole audiences of people writhe and blaspheme and wrestle with lay ministers bent on forcibly evicting scores of demons.

“American Exorcism” is a very interesting, compulsively readable look at a phenomenon that most people probably weren’t very aware of, questions about the existence of the Antichrist aside.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

By Gayle White

[excerpted]

ANDREA YATES goes on trial Monday in a Houston courtroom for drowning her five children. Her lawyers blame a severe case of postpartum depression. But Yates herself raises another, much murkier issue – the possibility of demonic possession.

She told doctors she wanted her head shaved to expose “666,” the mark of the Antichrist, on her scalp.

MIGHT YATES NEED AN EXORCISM?

Michael Cuneo, author of “American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty,” calls exorcism “a burgeoning, booming business in the United States.” People who claim to be demonized are often evading responsibility for their own thoughts and actions, he says. “We’re a culture of victimization. Exorcism can be a moral cop-out.”

Yates may sincerely believe she is possessed, Cuneo says, but “overwhelmingly people who seek out exorcisms are suffering from some neurological, psychological or psychiatric disorder.”

Cuneo observed more than 50 exorcisms for his book – Pentecostal, charismatic, evangelical and Catholic both officially sanctioned and “bootleg.”

“What I saw in many cases were troubled people, confused people, desperate people, people who wanted to believe they were demonized and that exorcism would cure them of their problems,” he says. “I generally thought that I could account for what I saw in nondemonic terms.”

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

NONFICTION

● “Harvard Diary II: Essays on the Sacred and the Secular” by Robert Coles (Crossroad, $20). A Pulitzer Prize-winning author shares his observations. (April)

● “The Smoke of Satan: Conservative and Traditionalist Dissent in Contemporary American Catholicism” by Michael W. Cuneo (Oxford, $25). An assessment of right-wing Catholic groups and of militant anti-abortion activism. (May)

● “After God: The Future of Religion” by Don Cupitt (Basic, $20). The author traces the move from traditional belief to cynicism to faith after the so-called death of God. (May)

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Now it’s more than just a battle of words.

Will violence decide the abortion issue?

By Delia M. Rios

[excerpted]

TWENTY-FIVE YEARS after the Roe vs. Wade decision, the nation has reached a great divide in the continuing struggle over abortion. The struggle has turned from a shouting match to a shooting war – one begun by people denounced as fanatics by mainstream leaders on both sides.

Now both sides are weary of the violence and have a common interest in stemming it. The key may lie in their ability to reclaim the public stage wrested away by the violent.

The common problem remains that the tactics of those on the fringe – whether they are called purists, militants or terrorists – have succeeded in one regard.

“Radical militants believe that when they protest, they keep the idea alive. In a sense, they’re right,” says Michael W. Cuneo, a professor of sociology and anthropology at Fordham University in New York and author of “Catholics Against the Church.” Cuneo has studied Catholic anti-abortion protesters in both the United States and Canada.

Yet, Cuneo says, what also happens is that “lunatics surface from the woodwork. And all the people out in the streets protesting wind up unwittingly contributing to their own demonization.”

The Record (North Jersey)

How to Protect Yourself from Evil Spirits

An Islamic View

By Misbahuddin Mirza

[excerpted]

BELIEF IN THE existence of Satan is one of several theological points that Christians and Muslims agree on. America’s fascination with the subjects of demonic possession and exorcism has produced a plethora of best-sellers and hit movies. Today, the number of officially appointed Catholic exorcists is on the rise.

According to Michael Cuneo’s book “American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty,” some charismatic Christian groups diagnose almost every evil as cases of demonic possession and attempt to perform exorcisms on almost everyone they see.

According to Islamic standards, such practices are misguided. In fact, they may harm the person believed to be possessed. Michael Cuneo writes that a Long Island, N.Y., mother killed her own daughter during a botched exorcism.

In Islamic law, there is no official title of “exorcist.” All Muslims are required to end oppression – whether it is caused by a jinni (a devil or demon) or a human.

Panama City News Herald (Florida)

Of Font & Film

Influence and Inspiration

By Michael Lister (Columnist)

[excerpted]

INFLUENCE IS AN interesting thing.

When “The Exorcist” was published I was 3 years old.

I was 5 when the movie based on it was released.

The book and the film had no impact on me at the time, but they changed the world I was so newly born into in ways we’re still discovering. They also were hugely influential on my fifth John Jordan novel, “Blood Sacrifice,” decades after they first came out.

In “Blood Sacrifice,” ex-cop/prison chaplain John Jordan investigates the death of a young woman who was undergoing exorcism when she was killed.

While doing research for “Blood Sacrifice,” I read the nonfiction book “American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty” by Michael Cuneo.

The book is described by its publisher as “a guided tour through the burgeoning business of exorcism and the darker side of American life. There is no other religious ritual more fascinating, or more disturbing, than exorcism. This is particularly true in America today, where the ancient rite has a surprisingly strong hold on our imagination, and on our popular entertainment industry. We’ve all heard of exorcism, but few of us have ever experienced it firsthand.”

“Publishers Weekly” had high praise for the book: “Lucidly written and riveting as any horror novel, Cuneo’s excursion into the darker paths of American faith offers a deeply disturbing, ironic vision of what [Cuneo] sees as the unintended consequences of popular culture for the modern religious imagination.”

I highly recommend Michael Cuneo’s “American Exorcism.”

The Post-Standard (Syracuse, NY)

Woman’s Mary Message Questioned

Experts raise red flag over words Skaneateles woman says she heard Sept. 11

By Renee K. Gadoua

[excerpted]

SOME EXPERTS HAVE expressed concern about the content of a message a Skaneateles woman reported receiving from the Blessed Mother shortly after the terrorist attacks.

“This is one of the chastisements. Further chastisements can be averted by prayer,” Mary S. Reilly reported the mother of Jesus Christ told her about 9:30 a.m. Sept. 11.

The Rev. Michael Minchan, co-chancellor of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Syracuse, said the Sept. 11 message includes a different tone and content from those Reilly has reported receiving during Wednesday night rosary recitations at the grotto outside St. Mary of the Lake Church in Skaneateles.

Although diocesan officials said they continue to monitor the situation, church officials have not launched a formal investigation of Reilly or her actions at the grotto.

But two experts on Marian apparitions said the Sept. 11 message raises a red flag about Reilly’s credibility.

The Rev. Thomas Thompson, Director of the Marian Library/International Marian Research Institute at the University of Dayton, seemed rattled as a reporter read the message last week.

“Stop. Don’t go on. I won’t talk about that,” he said. “I will not comment on that. That is definitely contrary to any Christian beliefs.”

Michael Cuneo, professor of sociology and anthropology at Fordham University, described the Sept. 11 message as opportunistic and lacking in genuine spirituality.

“This seems outright obscenity,” Cuneo said. “Claiming the terrorist attacks are a supernatural punishment? This is antithetical to the best of Roman Catholic tradition.”

The message is disrespectful to the victims of terrorism, he said.

“It’s unspeakable cruelty to say the attacks are divinely inspired,” said Cuneo, author of “The Smoke of Satan,” a book critical of some conservative elements within the Catholic church.

Reilly, 43, has not returned numerous phone calls to her home or workplace, Art n’ Soul, a shop in Skaneateles.

Christianity Today

By Agnieszka Tennant

[excerpted]